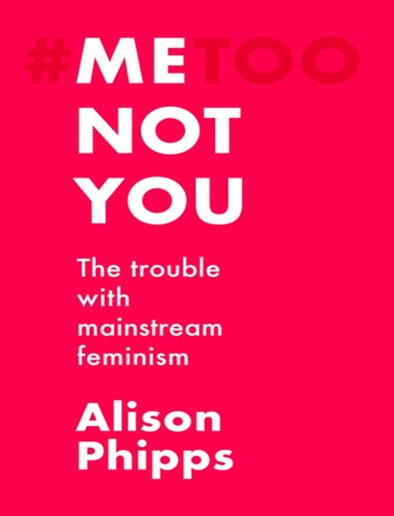

Me, Not You: The Trouble with Mainstream Feminism

Me, Not You: The Trouble with Mainstream Feminism

Alison Phipps

Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2020

205 pages

ISBN 978 1 5261 4717 2

Me, Not You: The Trouble with Mainstream Feminism written by Alison Phipps and published by the Manchester University Press in 2020 is a book which aims to highlight, as its title explicitly suggests, the problematic aspects related to contemporary mainstream Feminism and the latter’s tendency to be related to whiteness and exclusionary Anglo-American politics. In her introduction, Phipps describes her work as a book about, “violence – especially the violence we can do in the name of fighting sexual violence” (Phipps 2020, 3). This sets the tone to the content of the latter and its problematization of the original, celebrity-led American version of the Me Too movement as well as white feminism in a more general sense. The introduction also includes a brief overview of what the feminist scholar refers to as ‘mainstream feminism’ or, in other words and as clarified by the author, of “Anglo-American public feminism” (Phipps 2020, 5) as well as the racial implications behind said form of hegemonic, hyper-exposed and represented feminism. She explains how the main aim of this book is to highlight how the contemporary mainstream feminist movement against sexual assault and harassment, exemplified by the #MeToo, tends to push aside and, in its own way, violently exclude women who do not belong to the cisgender, white, middle to upper class woman category. She aims her writing towards white women and feminists and educators who, “like [her], are interested in doing their feminism differently” (Phipps 2020, 11). The book is divided into six chapters which draw from Black feminist theory in an effort to decentralize the discourse on sexual violence and make much needed observations on mainstream feminism’s tendency to co-opt, “the work of women of colour, while refusing to learn from them or centre their concerns” (Phipps 2020, 3).

The first chapter entitled “Gender in a Right-Moving World” begins with a brief retelling of the events which were uncovered as a result of Dr. Christine Blasey Ford’s testimony against Brett Kavanaugh. Phipps describes how, while Kavanaugh ended up being appointed as an Associate Justice of the American Supreme Court, Ford’s actions led to an outpour of support on a national and international level (Phipps 2020, 13) but also, and most importantly, highlighted the importance of what Angela Davis refers to as the, “intersectionality of struggles” (Davis as cited in Phipps 2020, 34) in fighting against the normative, racist, capitalist and patriarchal values often used to generalize and homogenize the narrative of sexual violence, therefore excluding minorities from it. Furthermore, in the same chapter, Phipps also discusses the role of far-right groups in the creation of these narratives by simultaneously, “weapon[zing] the idea of ‘women’s safety’ against marginalised and hyper-exploited groups” (Phipps 2020, 31) while trying to control women’s reproductive rights and promote anti-women laws.

The second chapter entitled “Me, not you” addresses the issue of whiteness within mainstream feminism and links it to the story behind how #MeToo went viral after being accidentally co-opted by American, white feminist actresses such as Alyssa Milano, Rose McGowan as well as other famous models, anchors and public figures who spoke out against Harvey Weinstein. As the chapter traces back Black feminism’s issues with white feminism, what stands out is the fact that what is problematized here is not any of these white women’s experiences with sexual assault or their participation in and popularization of the conversation around it but their tendency to speak over and take over marginalized groups’ voices and projects while doing so (Phipps 2020, 37). This marginalizing aspect of white feminism led, according to the author, the movement to neglect the theorization of the intersections between race, gender and class therefore often limiting the discussion of violence, especially during its second wave of feminism, to the phallus and the locating of violence, “in the male body, while women were the violated ones” (Phipps 2020, 44).

The next chapter takes the name of the concept it focuses on, namely “Political whiteness.” Here, Phipps builds on the ideas found in Daniel Martinez HoSang’s conceptualization of the latter so it, “describes a set of values, orientations and behaviours that go deeper than that [whites-first ideology]” (Phipps 2020, 59). She explains how these include, “narcissism, alertness to threat and an accompanying will to power. And perhaps most crucially, they characterise mainstream feminism and other politics dominated by privileged white people” (Phipps 2020, 59). In this chapter, two arguments stand out: the fact that one does not have to be white to play a role and perpetuate political whiteness as well as the fact that white women can simultaneously be victims of sexual violence while upholding other forms of violence such as racial capitalism and white supremacy (Phipps 2020, 62). This goes back to the idea that the problem with white feminism is not necessarily in the participation of white women in the fight against sexual violence but their simultaneous involvement in that fight and their committing of acts of violence against other minorities.

Chapter four called ‘The Outrage Economy’ makes the link between political economy and the narrative built around trauma and survivorhood within contemporary feminism, especially in light of the Me Too movement. Essentially, Phipps argues that feminists use trauma and the expression of it, namely outrage, as a, “form of capital that can be accumulated” (Phipps 2020, 99). In the context of #MeToo and in the age of communicative capitalism (a concept she borrows from Jodi Dean), what this capitalization of trauma shows is that some people’s voices are worth more than others and that the use of the media for outrage tends to bring out the carceral tendencies of the movement. This movement is linked to the fact that the higher profile individuals’ claims, regardless of how truthful they may be, often lead to more incarcerations than lower profile victims’, especially if they are facing a higher-profile abuser due to the fact that their trauma is not capitalized and pushed forward by collective outrage. Essentially, the more attention, or in other words capital, one party is able to gather may, in theory, play an important role in determining who will be incarcerated or not. She drives this point home by examining how marginalized women such as sex workers and transexual women have been ‘priced out’ of this economy of outrage and how their abusers often do not suffer the consequences of their actions. Another aspect she points out is the performative nature of said economy since the participation in such display of outrage online through the use of the hashtag rarely lead to concrete, long-term changes and support in survivors’ fight for justice.

The second to last chapter entitled “White feminism as war machine,” was inspired by Achille Mbembe’s concept of the ‘war machine’ and demonstrates the harm that can be done by while bourgeois women in an attempt to defend others. Here, Phipps takes the arguments made in the previous chapter and combines it with the notion of whiteness to prove how public expressions of anger and outrage channeled through whiteness often focuses on punishment and demands for the incarceration not necessarily of the culprit but of a culprit (Phipps 2020, 124). In those instances, and based on various case studies, the writer argues that, often times, marginalized people end up being collateral damage to the feminist war machine as a result of their overall higher likeliness to be, be it rightfully or wrongfully, incarcerated. Here, as Phipps bases her analysis on the United States’ social context, an easy way to prove the validity of her claims is to compare them to the statistics provided by the United States’ Department of Justice. What can be inferred by the official statistics is the fact that, not only is the number of male prisoners significantly higher in 2019 than that of women prisoners, as problematized by Phipps in this chapter, race significantly impacts the number of incarcerated men. Indeed, the number of African American men in prison is five times higher than that of white Americans but also double the number of male prisoners from Hispanic origins (Carson 2020). These numbers highlight how men are overall more likely to be incarcerated but also how men who specifically come from a Hispanic or African American background are even more likely to be.

The last chapter called “Feminists and the far right” builds on the idea that white feminism is a form of war machine to arrive to the conclusion that, not only do contemporary white feminists use and sacrifice the members of marginalized groups for their own benefits, whether economic, emotional or judicial, they also, “position[…] them as enemies” (Phipps 2020, 133). In fact, Phipps, once again heavily referring to the fight for transgender women’s rights, highlights how many reactionary feminists often align with the far right in an attempt to hinder the agenda of the marginalized groups left behind by this white feminist war machine. This is done under the pretext of claiming back, protecting and fighting for the safety of women and womanhood (Phipps 2020, 152). This is especially relevant nowadays as the Roe v. Wade abortion rights bill, which is based on the 1973 Supreme Court ruling in relation to the case which bares the same name, was overruled by the Senate as of May 2022. As such, and in the current Biden-hostile American political climate, the narratives described by Phipps in this chapter can be seen put into action through the conservative, pro-life members of the senate but it is also currently utilized by far-right media to gain the public opinion’s support on the matter. Likewise, in light of this bill, a similar line of argumentation has been adopted by many feminist scholars who either label themselves or have been labelled as “pro-life feminists” (Becker 2021), which, once again, testifies to the relevance of Phipps’ criticism of Anglo-American feminism, especially when it comes to the American context.

Overall, while Phipps targets a specific audience, she writes her book in a concise, accessible and easily digestible manner which makes of Me, Not You a useful resource for anyone interested in the problematizing of contemporary American feminism, the monetization of political outrage, sexual violence, carcerality and how these issues interact within the historical, socio-cultural and political framework created by the Me Too movement. Despite the fact that her criticism can be applicable to most of the world as a result of the fact that #MeToo’s strength is its significant presence on various digital social media platforms, making it and keeping it global, the professor’s arguments are particularly relevant to the study of such issues within the Anglo-American ideological context which she refers to as mainstream feminism. While, at times, Phipps criticism of white feminism, despite being valid to some extent, tends to fall into a heavily white guilt tainted discourse, she makes important connections between the theoretical thoughts found within Black feminism and the current trends in the white-centered Western feminism. Most importantly, Phipps successfully opens the discussion on the flawed nature of the Hollywood stars led version of the Me Too movement which went viral in 2017 and builds a foundation upon which other scholars can construct their own alternative readings of the latter.

Works cited

- Phipps, Alison. 2020. Me, Not You. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

- Carson, E. Ann. 2020. “Prisoners in 2019.” Bureau of Justice Statistics. October 2. Accessed May 2022. https://bjs.ojp.gov/content/pub/pdf/p19.pdf.

- Becker, Amanda. 2021. “What ‘pro-life feminists’ are arguing in the Mississippi abortion case.” November 30. Accessed May 2, 2022. https://19thnews.org/2021/11/pro-life-feminists-supreme-court/.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.