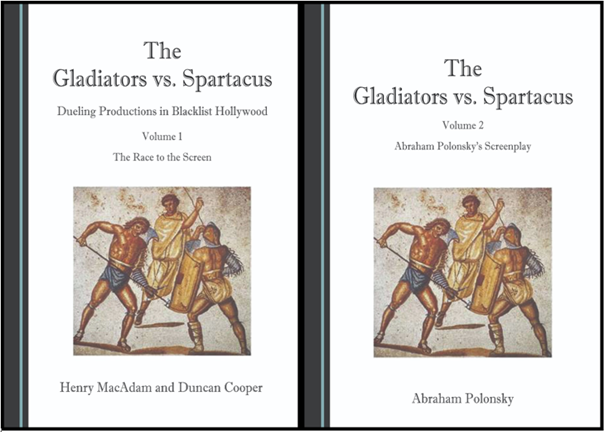

The Gladiators vs. Spartacus: Dueling Productions in Blacklist Hollywood

The Gladiators vs. Spartacus: Dueling Productions in Blacklist Hollywood

Henry MacAdam, Duncan Cooper, and Fiona Radford

Newcastle: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2020

2 vols. 486 + 621 pages

ISBN 978-1-5275-5699-7 and 978-1-5275-6020-8 (hardcover)

ISBN 978-1-5275-7153-2 and 978-1-5275-7154-9 (paperback)

Rarely does one come across a book which is devoted in its entirety to a single, unsuccessful (sic!) film project, and much less one that comes in two tomes of monstrous length, totaling 1107 pages. A casual observer might easily, and understandably, consider such an unusually lengthy text as a case of frivolous academic infatuation blown out of proportion. Yet, as I am going to show below, The Gladiators vs. Spartacus is nothing of the sort: it is a refreshing and enjoyable read, a major contribution to film history, and has strong relevance both in and beyond academia.

To start with the smallest group benefiting from this publication, the painstaking documentation of the failed project to film Koestler’s first published novel, The Gladiators (1939), is certainly of interest to Koestler scholars. This is since, until very recently, not even this specialist circle was aware even of the mere existence of such a project. As late as until five years ago, there was no mention of the failed plans for a Hollywood adaptation of The Gladiators in any of Koestler’s biographies and autobiographies. Koestler himself made no mention of it in either Arrow in the Blue (1952), The Invisible Writing (1954) or Stranger on the Square (1984). Nor did Iain Hamilton in his Koestler: A Biography (1982), David Cesarani in his Arthur Koestler: The Homeless Mind (1998) or Michael Scammell in Koestler: The Literary and Political Odyssey of a Twentieth-Century Skeptic (2009). The first biographer who has noticed its existence is Edward Saunders:

"The Spartacus story has since become ubiquitous, but Koestler’s The Gladiators preceded the 1951 novel Spartacus by Howard Fast which was made famous by Stanley Kubrick’s film in 1960. It is even said that the film’s producers had originally been keen to adapt Koestler’s novel, not Fast’s, and that Kubrick wanted to introduce elements of The Gladiators into the movie. This was fiercely resisted by the scriptwriter, Dalton Trumbo, for complex political reasons (like both Koestler and Fast, Trumbo was also an ex-Communist)." (Saunders 2017, 54)

While Saunders is oversimplifying the story and imprecise about some details in the quote above,1 at least he has noticed a film project that has passed under the radar of most scholars for decades.

Saunders’s primacy is, of course, only true if one limits their focus to biographies. While standard monographs on Koestler’s fiction are just as unaware of the film project not only in the Anglophone context (Levene 1984, Pearson 1978), but also in the German (Weßel 2021, Prinz 2011, Strelka 2006) and Hungarian one (Körmendy 2007, Szívós 2006, Márton 2006), a handful of scholars, most of them contributors to the reviewed volume, broached the topic earlier than Saunders did. In fact, Saunders’s account is merely a rough summary of the claims in Brent D. Shaw’s (2005) study and Duncan L. Cooper’s discussion of the failed film project (2007a). Besides Shaw and Cooper,2 Henry Innes MacAdam also published three articles (2006, 2012, 2015) partially or completely devoted to this film project that predate Saunders’ book (albeit he does not cite any of them), and so did Fiona Radford (2017). In fact, as MacAdam points out in The Gladiators vs Spartacus, in addition to these more explicitly relevant sources, the failed film project was also discussed at length in Kirk Douglas’s two memoirs, The Ragman’s Son (1988) and I Am Spartacus (2012), while probably the earliest, albeit “cryptic reference” (Macadam et al. 2020, vol. 1, xviii) to the project appeared in Bruce Cook’s (1977) eponymous biography of Dalton Trumbo. Yet, these three latter sources were almost guaranteed to stay unknown to Koestler-scholars, given that unless one both already knew about the attempt to film The Gladiators, and, at the same time, also that this attempt took the form of a race to the screen with Stanley Kubrick’s Spartacus (1960), starring Kirk Douglas, with a screenplay by Dalton Trumbo, they would have probably not even been aware of the existence of these books, much less thinking of searching for information on the filming of Koestler’s novel on their pages.

Bringing together virtually all scholars who have published on the failed film project (Duncan L. Cooper, Henry MacAdam, and Fiona Radford), and incorporating the results of the others (Brent D. Shaw and Bruce Cook) as well as a whole range of other primary and secondary sources, for the Koestler-scholar, this book is a major event. Besides an exhaustive and definitive discussion of the complete history of the film project itself, it also provides, for the very first time, an analysis of the critical reception of Koestler’s novel. In addition, in a separate chapter, it conveniently collects, and comments on, available information on the historical sources Koestler used for writing his novel and on his literary influences. Just as useful for the Koestler-scholar is the more than thirty pages long section commenting on all the archives and special collections consulted during the research, most of which are relevant not only for those interested in this film project, or even The Gladiators, but also for the general field of Koestler Studies. These holdings are rarely discussed together, much less in this much detail, and as the authors themselves correctly point out: “A discouraging aspect of our research is the realization that most of the institutions we contacted were unaware of the holdings at other entities” (MacAdam et al. 2020, vol. 1, 391). The same probably applies to Koestler-scholars as well: only a portion of them relies on archival material, and typically even those, myself included, only consult the Arthur Koestler Archive at the Centre for Research Collections of the University of Edinburgh Library, but not the A. D. Peters Collection at the Harry Ransom Research Center at the University of Texas at Austin,3 much less the collections at the Russian State Military Archive (Российский государственный военный архив).4

A second, and admittedly much larger, group that profits from the publication of this book are scholars of American film history. In describing the rivalry and intertwined history of the efforts of Yul Brynner’s production agency, Alciona Films, intent on filming Koestler’s The Gladiators, and Kirk Douglas’s own Bryna Pictures, aiming at adapting Howard Fast’s (1951) Spartacus, the reviewed book helps filling in many of the blind spots and unknown details of the history of Stanley Kubrick’s iconic Spartacus (1960), the end result of the latter of the two rivals’ ultimately successful venture. Likewise, not only the antagonists (i.e. Yul Brynner and Kirk Douglas) of this rivalry, but also most of their team members are also major names in film history as directors, screenwriters, actors or producers. Besides Kubrick, such figures have significant roles in this duel as Martin Ritt, Dalton Trumbo, Abraham Polonsky, Anthony Mann, Ira Wolfert, Lew Wasserman, Laurence Olivier or Arthur B. Krim.

In addition, and just as importantly, as the book’s subtitle itself clarifies, the story of the two dueling Spartacus-films, is also a story of the Hollywood blacklist, or rather its successful breaking by Dalton Trumbo with the help of Otto Preminger, Kirk Douglas and Arthur B. Krim, amongst others. While this story is not unknown, this detailed and painstaking account of the story of two blacklisted writers, Abraham Polonsky and Dalton Trumbo, secretly working on rival projects’ screenplays, offers exciting new insights of the administrative, political as well as psychological aspects of this ultimately successful journey.

At least until the eventual publication, if it ever happens, of John Bokina’s Images of Spartacus,5 Henry Innes MacAdam’s historical survey of literary and film adaptations of the Spartacus-story in the past two hundred years might also attract film (as well as literary) scholars to The Gladiators vs. Spartacus. While the topic has been touched upon, and discussed by many, including MacAdam himself, as well as Brent D. Shaw, this roughly thirty-page account is useful in that it is brief, yet comprehensive, thus an ideal starting point for those interested in Spartacus-adaptations.

Finally, and this is where the interest of film scholars overlaps with that of the third group of readers, i.e. the staff of film and television production agencies, The Gladiators vs Spartacus is a groundbreaking publication in that it publishes, in its entirety, and for the first time, Abraham Polonsky’s long-lost screenplay, with detailed commentary. Since the screenplay is visually evocative, fresh, and action-packed yet thought-provoking in its own right, it could easily serve as the basis for either a new Spartacus-film, or a short series. While producing two concurring films on the same topic more than sixty years ago might not have been economically feasible, with the return into vogue of magnificent historical spectacles at around the millennium, their continuing popularity ever since, and the availability of high quality CGI, Arthur Koestler’s novel, and Abraham Polonsky’s screenplay, should finally receive their well-deserved filming.

In other words, albeit unusually long, and at first sight surprising, The Gladiators vs. Spartacus: Dueling Productions in Blacklist Hollywood is an intriguing, timely and academically rigorous publication that can be of interest for a whole range of readers from Koestler experts through film scholars to industry experts. With publishing houses increasingly limiting their focus on monographs with a standard length of 100,000 – 120,000 words, and to topics broad enough, and mainstream enough, to interest a wide range of readers, actively steering clear of single-author and single-novel studies, edited volumes and topics casually marked unmarketable, Cambridge Scholars Publishing also deserves praise for publishing a text which, at first sight, shows clear signs of a niche project, and allowing it to be published in the length that this gem of philological research deserves, rather than squeezing it into the confines of the standard industry length. This shows that independent academic publishers have a clear place and well-defined role in the market, and albeit endangered by constant buyouts, are more necessary than ever if we are to avoid the uniformization of research in the humanities.

Works Cited

- Browder, George C. 1991. “Captured German and Other Nations’ Documents in the Osoby (Special) Archive, Moscow.” Central European History 24 (4): 424-445.

- Carr, Gerald Anthony. 1987. “The Spartakiad: Its Approach and Modification from the Mass Displays of the Sokol.” Sport History Review 18 (1): 86-96.

- Cesarani, David. 1998. Arthur Koestler: The Homeless Mind. London: Heinemann.

- Cook, Bruce. 1977. Dalton Trumbo. New York: Scribner.

- Cooper, Duncan L. 1991a. “Dalton Trumbo vs. Stanley Kubrick: Their Debate over Arthur Koestler’s The Gladiators.” Cinéaste 18 (3): 34-37.

- —. 1991b. “Who Killed Spartacus?” Cinéaste 18 (3): 18-27.

- —. 2007a. “Dalton Trumbo vs. Stanley Kubrick: The Historical Meaning of Spartacus.” In Spartacus: Film and History, edited by Martin M. Winkler. Malden, MA: Blackwell. 56-64.

- —. 2007b. “Who Killed the Legend of Spartacus? Production, Censorship, and Reconstruction of Stanley Kubrick’s Epic Film.” In Spartacus: Film and History, edited by Martin M. Winkler. Malden, MA: Blackwell. 14-55.

- Douglas, Kirk. 1988. The Ragman’s Son: An Autobiography. New York: Simon and Schuster.

- —. 2012. I Am Spartacus: Making a Film, Breaking the Blacklist. New York: Open Road.

- Fast, Howard. 1951. Spartacus. New York: Howard Fast.

- Hamilton, Iain. 1982. Koestler: A Biography. London: Secker and Warburg.

- Kennedy Grimsted, Patricia. 1997. “Displaced Archives and Restitution Problems on the Eastern Front in the Aftermath of the Second World War.” Contemporary European History 6 (1): 27-74.

- —. 2017. “Pan-European Displaced Archives in the Russian Federation: Still Prisoners of War on the 70th Anniversary of V-E Day.” In Displaced Archives, edited by James Lowry. New York: Routledge. 130-156.

- Koestler, Arthur. 1939. The Gladiators. London: Jonathan Cape.

- —. 1952. Arrow in the Blue. New York: Macmillan.

- —. 1954. The Invisible Writing. New York: Macmillan.

- Koestler, Arthur, and Cynthia Koestler. 1984. Stranger on the Square. Edited by Harold Harris. London: Hutchinson.

- Körmendy, Zsuzsanna. 2007. Arthur Koestler: Harcban a diktatúrákkal. Budapest: XX. Század Intézet.

- Kubrick, Stanley, dir. 1960. Spartacus. Universal City: Universal.

- Levene, Mark. 1984. Arthur Koestler. New York: Frederick Ungar.

- MacAdam, Henry Innes. 2006. “Arthur Koestler’s The Gladiators and Hellenistic History: Essenes, Iambulus and the ‘Sun City,’ Qumran and the DSS.” Scripta Judaica Cracoviensia 4: 69-92.

- —. 2012. “Spartacus Redivivus: Hollywood’s Blacklist Remembered.” Left History 16 (2): 49-71.

- —. 2015. “Dramatizing Roman History: Spartacus in Fiction and Film.” The RAG 10 (2): 1-5.

- Márton, László. 2006. Koestler, a lázadó. Budapest: Pallas.

- Pearson, Sidney A. 1978. Arthur Koestler. Boston: Twayne.

- Prinz, Elisabeth. 2011. Im Körper des Souveräns: politische Krankheitsmetaphern bei Arthur Koestler. Wien: Braumüller.

- Radford, Fiona. 2017. “Hollywood Ascendant: Ben-Hur and Spartacus.” In A Companion to Ancient Greece and Rome on Screen, edited by Arthur J. Pomeroy. Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell. 119-144.

- Saunders, Edward. 2017. Arthur Koestler. London: Reaktion Books.

- Scammel, Michael. 2009. Koestler: The Literary and Political Odyssey of a Twentieth-Century Skeptic. New York: Random House.

- Shaw, Brent D. 2005. “Spartacus Before Marx.” Princeton/Stanford Working Papers in Classics 110516. DOI: 10.2139/ssrn.1426840

- Strelka, Joseph Peter. 2006. Arthur Koestler: Autor – Kämpfer – Visionär. Tübingen: Francke.

- Szívós, Mihály. 2006. Koestler Arthur: Tanulmányok és esszék. Budapest: Typotex.

- Weßel, Matthias. 2021. Arthur Koestler: Die Genese eines Exilschriftstellers. Berlin: Peter Lang.

Notes

1 Perhaps most explicitly so with his claim that the Spartacus-story has become ubiquitous only after Koestler’s novel was written (cf. Carr 1987, Shaw 2005). ↩

2 Saunders, however, does not refer to Duncan L. Cooper’s other relevant chapter in the same volume (2007b), nor does he seem to be aware that these two chapters are slightly reworked versions of Cooper’s much earlier publications (1991a, 1991b) on the same topic in Cinéaste. ↩

3 Augustus Dudley Peters was Koestler’s literary agent for most of the latter’s career. ↩

4 The authors somewhat confusingly refer to this institution as the “Former KGB Headquarters in Moscow” (MacAdam et al. 2020, vol. 1, 402), which is rather imprecise. The building of the former KGB Headquarters, popularly known as Lubyanka, located at 2 Bolshaya Lubyanka, is now used by the Federal Security Service of the Russian Federation (Федеральная служба безопасности Российской Федерации), most frequently referred to by its acronym, FSB. The Russian State Military Archive, where these holdings are actually kept, is located at 29 Admirala Makarova, more than 14 km from the Lubyanka. The root of this confusion is probably David Cesarani’s (1998) somewhat sensationalist and biased biography where he refers to these papers held in Moscow, throughout his book, as “the KGB ‘Special Archive’” (ix, x, 132, 148), although his actual reference, in footnote, is to the holdings of the “Centre for the Conservation of Historical Documentary Collections, Moscow” (586) or Центр хранения историко-документальных коллекций, also cited by Michael Scammell (2009) under the latter name in his later biography throughout (600-612). Since the Centre for the Conservation of Historical Documentary Collections was indeed called the Central State Special Archive of the USSR (Центральный государственный Особый архив СССР) before 1992 (Kennedy Grimsted 2017, 133), Cesarani’s reference to the “Special Archive” is correct. It is also true that even the existence, and much more so the contents, of this archive was a well-kept secret (Kennedy Grimsted 1997, 57-8), and so is the claim that it was established for the operational aims of Soviet intelligence services (55-56). It was, however, established on March 9, 1946 by the People’s Commissariat for Internal Affairs of the USSR (Народный комиссариат

внутренних дел СССР), commonly known by its abbreviation, NKVD, at which point the KGB (Комитет государственной безопасности, Committee for State Security) did not yet exist. Likewise, at its founding, the “Special Archive” was aimed at a whole range of security agencies that might profit from it in their operational work (56). It is also worth mentioning here that while some of Koestler’s papers are indeed in Moscow, part of the Special Archive’s original collections of his papers were apparently “returned to [the] former DDR” (Browder 1991, 441). Where they exactly are, and what exactly they are, unfortunately, remains a mystery to me. ↩

5 That book was first scheduled for publication in 2007 by Yale University Press, but its printing has been continuously postponed ever since. ↩

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.