Robert Eggers’ The Lighthouse was released in 2019. The film is supposed to be an adaptation of an unfinished horror story written by Edgar Allan Poe. With its slow, gothic, psychological centrifugation, however, the film says a lot more about the time when it was created than about the era where the story originally takes place. In my essay, I would like to offer an interpretation of the plot through the ideas of Sigmund Freud, in particular his Beyond the Pleasure Principle, while I will also present some arguments in favor of the thesis that the film’s uncanny nature reaches beyond the framework of its aquatic gothic genre and reflects more of a hauntological,1 post-historical, or at least a strongly post-modern critical perspective.

Horror in the Tower, with Mermaids

The Lighthouse is a gothic horror movie endowed with aquatic characteristics by some of its thematic motifs, like the island encompassed by the sea, the mermaid and the sailors’ superstitions. I would like to begin my analysis with a deeper explanation of the symbolism of the location of the film or, more specifically, the symbolism of land and water. While this extreme situation has a lot to say about the relationship between human beings and nature, it tells us at least as much about the human beings’ relationship to themselves.

A possible interpretation of the encounter of the island and the ocean in the film is that it is the confrontation of the conscious (the island) and the unconscious (the water) and it is this confrontation that guarantees the plot’s surrealistic-horroristic style. The action itself takes place in “reality” while it is also a depiction of the desperate struggle of our protagonist, Ephraim Winslow2 with the horrors of his unconscious. This central motif exemplifies the influence of surrealism on the so-called genre of aquatic-gothic, for surrealism, as a movement critical of modernity, instead of the mainland that is perfectly known and therefore deprived of mysticism, focuses on the “unknown depths of the sea gulf” as “the magical place represented by the dreams and/or the unconscious that violates the rule of logic and […] where the Übermensch can free its spirit by nightmarish eroticism” (Nemes 2018).

One of the characteristics of aquatic gothic is that it “transposes the sublime and unknowable forces with (amongst others) horroristic features to nature” (Ibid.). It prevails and also expands in the case of The Lighthouse as well, as the thrilling, mystical effect of the film is brought about not only by the haunted nature of the lighthouse and the nodus organizing around it, but the particular relationship between a human being and its ever-dominating unconscious. Freud calls it the third great insult against humanity (Freud 1963)3; and the film articulates an exceptional synthesis of the experience of sublime as well: Winslow is not astonished by the incomprehensible infinity that he encounters (within himself) by the magnitude of nature, but it is his unconscious, this quasi-infinite force inside him (as in every human being) that crushes him. In other words, it is not or not only a kind of cognition of self that happens when the sea (metaphorically) washes to shore the “insides” of Winslow but he is squashed and torn to pieces by terror.

Another form of the sublime is present in the movie: the sublime caused by seeing or not being able to see at all. Winslow provokes nature with the butchering of the seagull and its rage comes in form of a storm so intense that it literally blinds our heroes, while they also get stuck on the island and cut off from the outside world forever. No wonder that their looks turn from the outside (both literally and figuratively) to the inside, to the lighthouse. Its beam embodies the paradoxical nature of light: while it cuts through the elemental darkness, it also dazzles both our heroes. Ultimately, this bewitching duality lures them into their doom. This is how the motif of lure, next to the blinding sublime, appears as another parallel between technology and nature, as the mermaid, in opposition with the lighthouse, is inviting us (back) to nature, to unite with it.

The use of eroticism and the anti-Enlightenment tone are both conspicuous in the movie, however, while Maldoror’s4 union with the shark was a symbolic gesture of him “leaving humankind behind, because in face of the moral failure of being human, the bestiality of nature seems much »cleaner« for him” (Nemes 2018), the sexual acts between Winslow and the mermaid are sins of the ancient hubris, the sin of the human being who revolts against superstitions and destroys nature (see the slaughtering of the seagull), while literally has his way with it as well, which is both a humiliation and a domination of not just the natural world, but the mythos as well. These acts in themselves foreshadow the fall of Winslow, as in the last sequence he lies dead on the same spot where he first found the mermaid. Furthermore, his only goal, a goal that he is even willing to kill for, becomes to get hold of the light. Vainly, because the moment he reaches it, he falls into the deep, to his death.

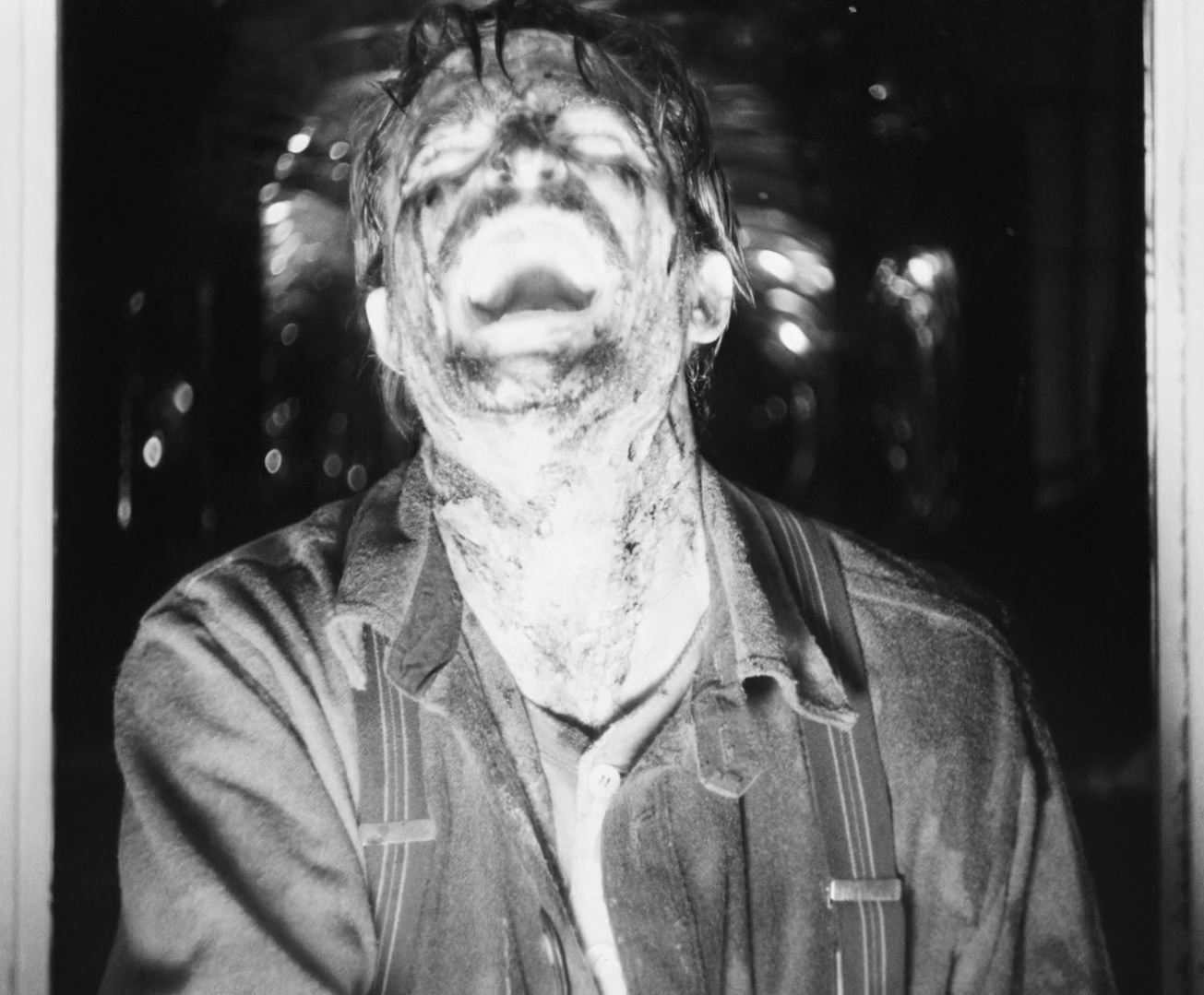

Being grasped: Hypnosis (1904) by Sasa Schneider (to the left) and Winslow’s Nightmare (to the right) (source: reddit)

One peculiarity of gothic horror films is that they commonly use the tool of referentiality. These gestures evidently strengthen the films’ embeddedness to their genre; moreover, the fact that the story is a Poe adaptation also highlights the film’s connection to the Gothic fiction. Xavier Reyes uses the term adaptational or referential channels in cases when adaptations, regardless their (movie)genre, contain the gothic elements of the works they are based on (Reyes 2019, 396). In The Lighthouse, Thomas recites sea prayers over and over and during their alcohol-fueled binges the two guys also perform some sea shanties; moreover, he also varies his use of words with references to mythical events and people. The use of intertextuality is intensified by the display of Sasha Schneider’s painting, Hypnosis on screen. This scene is of great importance, because it takes place immediately after one of the emotional peak points of the film, after Winslow had revealed his true identity (that he bears the name of a dead man) then faced his own counterpart, his Doppelgänger. This encounter is followed by the intertext, Winslow is turning his face to the opposite direction to find the naked Thomas standing in front of him while being “whipped around by the vice-like grip of the naked Old, who holds him hostage to his spell” (Russel 2020). The spell in this case is the outflowing light beam from Thomas’ eyes that eerly resembles to the blaze of the lighthouse. The only relevant difference from the original [painting] is the posture of the bodies, because in the movie Thomas is towering over the kneeling Winslow, symbolizing the permanent and unbreakable superior position of the lighthouse, the beam and himself.

The use of intertextuality has a dual effect on the movie. Once, as I have mentioned before, it makes the film more embedded to the genre of aquatic gothic. The scenes when Winslow calls Thomas by the name of Captain Ahab (the protagonist of Moby Dick [1851] written by Herman Melville) or when in one of Winslow’s visions the old man appears as Davy Jones, the captain of the Flying Dutchman well exemplify this connection. That being said, these references are pointing towards “both directions”, which guarantees them a strong myth-shattering effect as well. When Thomas, while being buried alive, pronounces Jones’ name and is murmuring a poem (about Protheus, Prometheus and the sea hugging around the world like a woman) with the intention of cursing Winslow (not for the first time in the movie), he is doing nothing but neutralizing the different possibilities of interpretation. Beyond the triviality that it is deepening Thomas’ mythical-religious bonding to the sea, it gives a recycling nature to the story as well. Following Thomas’ way of thinking the “new” could not be anything else but the embodiment of the “old” (Winslow being the embodiment of Prometheus in this case), however, saying it outright makes the whole phenomenon recycled, because the incarnation of the myth seems unreal both for the characters and the audience as well. To some extent, it generates the hauntology of the movie, because it calls attention to the fact that not only the viewers but the characters themselves interpret every new experience through this fixed world of myths: in this sense, haunting is not something “supernatural”, but a most fundamental part of experience.

Style Ghosts

The concept of hauntology becomes clear from the aspect of film history. The fact that The Lighthouse is from 2019 but was created as a black-and white movie, in the aspect ratio of 1,19:1 and was recorded through “ninety years old” optics while the audio track is in mono implies an unusual, likely self-serving and arty creation. However, it becomes clear from the statements of Eggers that there were strong arguments in favor of these decisions: once, they wanted to create a claustrophobic atmosphere, similar to Fritz Lang’s M (1931), since both Eggers and Jari Blaschke (the cinematographer of the film) are huge fans of the German Expressionism, in particular the movies of F. W. Murnau and Fritz Lang (Barrle 2020); on the other hand, mainly we see the silhouette of the lighthouse in its totality, while the two men are in narrow, close-up compositions. It seems logical to decide on a stretched, vertical cut out instead of the originally planned ratio of 1.33:1 (Bouder 2019; Robinson 2019).

The era of the plot (the 1890s), the extreme location and the repeatedly appearing figures of monsters also relate the film to the German Expressionism, to which it is also typical of having stories that “take time in a privileged moment of history (Paul Wegener: The Golem, 1920; F.W. Murnau: Faust, 1926; Fritz Lang: Metropolis, 1925; Die Nibelungen, 1923-24) and never in the present, and they often scare their audiences with dreadful, fantastic creatures” (Kiss 2001). There is a clear connection between the lighting of different scenes and the characters’ state of mind, the increase of insanity makes the film’s visuality, especially its lighting technique, more and more excessive. I have to stress the fact, that whilst visuality gradually gets radical, the source of light seems diegetic during the whole movie. The slowly breaking up madness is not supported by the installation of an “artificial” illuminant, but the natural lights getting unnaturally intense, even in the delirious dream scenes like the previously mentioned Doppelgänger encounter. I only mention it as a matter of interest that, as Miklós Kiss states, in expressionist cinema “set designers are nearly equal partners of the directors, because their help is the only way to call to life the weaponry to create an atmosphere implicated in the scripts” (Ibid.) – Eggers and his team built a real lighthouse just for this film.

Admittedly, these are quite strong influences, nevertheless it would be inaccurate to claim The Lighthouse to be a German Expressionist film, chiefly because the movement is tied to a specific time and location (Ibid.). While “the directors of the stories called to life in the expressionist cinema are directly or indirectly reaching back to the mystic, haunted atmosphere of the German Romantic (nightmare) represented by Hoffman” (Ibid.), the writer of the adapted novel, Edgar Allan Poe, was all doubts from the USA, just like the director of the film, Robert Eggers, as well.5 Consequently, it would be better to associate the film with the studio movies of the 1930s Hollywood, more specifically with the fantastic movies produced by Universal in this time, because those films were also highly influenced by the avant-garde movements of the previous decades. I am referring to movies like Dracula from Tod Browning (starring Béla Lugosi), Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde directed by Rouben Mamoulian or James Whale’s Dr. Frankenstein (and its sequels). All three of these so-called Universal-horrors were released in the same year, in 1931, and it is safely adjustable that they did not just “apply the results of the German Expressionism” but innovatively used the cinematic tools of German creators emigrated to the USA, like Karl Freund,6 the cinematographer who “previously elaborated his lighting technique, the clair obscure in his home country” (Pápai 2001).

These are important things to state, because Eggers’ film follows the trails made by the Universal horrors in the 1930s not only with its plot, but with its cinematic language (for example with the minimal use of montage) and how he technically implemented the staging. Dr. Frankenstein, beyond that it shares a similar system of motifs with The Lighthouse (in the first half of the movie Frankenstein, imagining himself to be God, is doing his scientific experiments in an abandoned watchtower; his creature is seeking the sunlight in a religious devotion, yet he is kept in a dungeon), echoes in the cinematic language of Eggers’ movie, for example the camera following our swaying and stumbling heroes, the feeling of movement created by the scanning carriaging in different spaces or with the close-ups of the monster’s face and this “kinship” is obviously present with nearly every member of this group of films mentioned, in different proportion and in various forms.

The monster of Frankenstein (James Whale – Dr. Frankenstein, 1931)

Dwight Frye in Dracula (Tod Browning – Dracula, 1931)

This is the point where the term of hauntology comes to the fore (again), because The Lighthouse, beyond that it tells a horror story that would have been popular as a studio movie in the 1930s, shares same influences with the movies of this era (expressionism and surrealism), moreover, due to its technical implementation, it looks like that it was made in the 1930s. In case of The Lighthouse, the interesting part is not that it tells us a story of an old world, but that we see this movie through the lens of an era when it was “in fashion” to screen these kind of stories for the first time. The “ghost of the past” literally embodies in this work of art of the present, because Eggers “calls to life” not just his film, but the experience of reception in a one-on-one way from a 90-year distance. When watching The Lighthouse we are not just watching an “old” movie but due to the effect of the film it feels like we are present in a former time. Eggers bears testimony to an interesting artistic creed with all this: he unties himself from the technical boundaries of his time, from that “burden” to try to create something new in the technically fixed environment of the present by consciously choosing a bygone method, however, that means that he has to sacrifice the traditional form of creative authenticity in a certain sense, or more precisely, he develops it in a strange, recycled form. The film itself becomes the time out of joint, the specter, by gaining its body from the past, but it still does not become the same as “those” in the 30s, it differentiates from itself due to the echo of time.

Simon Reynolds in his Retromania: Pop Culture’s Addiction to Its Own Past deals in depth with the subject of hauntology as something that fundamentally determines contemporary (pop)culture. He mentions an exhibition named Haunted that took place in New York in 2010 and its catalogue stated that the works of arts and recordings exhibited there were “ghostly reminders of lost time and the elusiveness of memory” and “By using dated stylistic devices, subject matter and technologies, such art embodies a longing for an otherwise irrecuperable past.” (Reynolds 2011, 329). Later he adds that when contemporary art is made “old” with damaging techniques during the creative process, it does not decrease the artistic value of it, but tearing up some associations within us and changing the experience of reception while also enriching it with emotions instead (Ibid., 331-332). These associations are set into motion by the feeling of nostalgia, however, we should add two highly important notes to that: as Reynolds states it in the preface, we are capable of feeling nostalgic to times (musically for example) that we did not live in (Ibid., XXVIII-XXIX); from this it plainly concludes that personal and collective nostalgia (just like self and society) are only seemingly separable, in practice it is impossible to draw a distinct line between them. Reynolds uses the golden age of rock music, as an example of nostalgia, and The Lighthouse recalls the birth of Hollywood’s golden age with the tool of intentional aging. Even if only a few of us has direct memories about how it felt watching a movie in the 1930s, in turn, nearly everybody has indirect memories about it (for example the stories of an old relative, pictures from a history textbook or when there is a film like this on TV).

Beyond the Event Horizon7

One main aspect of the movie is time: the presence of monotony is intense in the plot and it is massively wounding the souls of our characters (and viewers’ as well).8 That being said, in this case we are not simply talking about monotony but the questioning of the passage of time itself as well. Both the characters and the material world are captured by the paralysis of timeless passivity and it seems like this world has entered the age of samenesses without a new, the lack of development and the age of recycling or as Arnold Gehlen called it, the age of crystallization.9 “In the absence of waiting for the future, humanity turns to the past instead” (Böhringer, Ibid.) which in this case means nothing less than our heroes, because both of them have to deal with major traumas, start endlessly replaying the past, because, as Freud states they are “psychically fixated on the trauma” (Freud 2003, 87).

The Lighthouse (Robert Eggers – The Lighthouse, 2019)

In connection with the aquatic gothic I have mentioned before that surrealism uses the infinite domain of the sea as a metaphor for the unknowable and unexplored realm of the unconscious. That is why it is important to examine the things washed ashore: a mermaid, whose figure is regularly returning in the hallucinations of Winslow; lobsters, the preparation of which Thomas is quite sensitive about; and a cut-off head with one eye. Because of the ontological state of this metaphor, only those things can emerge from the sea that our heroes have been already in possession of. The story turns into horror instead of drama because, in opposition to for example a “Bergmanian analysis” in which the analysis is some kind of an “accounting with what we have” (Böhringer citing Benn, Ibid.) and a failure of facing the past as a tool for self-creation (in a simplified way of speaking),10 in The Lighthouse this past is turning against our heroes and ultimately leading to their downfall.

This story is not simply about two men going crazy on an island and murdering each other. First of all, they are going through a so called “deterioration”, during which nature is discrediting the Enlightenment, recapturing the human being itself while turning it from a conscious being into a delirious, instinct driven creature. The self of the present, that is always inevitably moving towards the future, is disappearing and a trait, an unprocessed, self-circulating past, a trauma is what remains of it. The ghost of the trauma-self becomes a specter by moving into Winslow’s and Thomas’ ruined bodies,11 our characters themselves turn into those haunted crumbles of ruins that usually serve only as the locations of similar stories. The peak of deterioration is the scene when Winslow literally turns into a seagull for a moment. His laugh is the same gloating cry that gulls make, moreover, he starts fluttering with his arms like they were wings. This whole process is quite similar to how Hartmut Böhme describes the way nature reclaims its territories in the form of crumbled and ruined buildings (Böhme 2016).

This time out of joint elevates the past and even the future to the level of the present. Furthermore, because time and space are inseparable from each other,12 therefore space dissolves as well when the border between “inside” and “outside” reality fades away. Beside his past traumas, Winslow is haunted by his future death that did not happen yet but seems inevitable. I have previously mentioned that there is a parallel between the mermaid and the lighthouse’s beam, since both of them can be associated with the motif of lure, in addition they also point to the same direction. Winslow, just like he has “drowned” on the first night,13 lies ashore at the end of the movie, on the same place and in the same posture as the mermaid did before.

At this point, I would like to present another possible horizon of interpretation, namely the critique of modernity and Enlightenment (as its antecedent). If we take the lighthouse’s beam as an allegory for modernity, then Thomas gives the impression of being the ruler of the old world(order), the protector of the past, while Winslow is the one who overthrows the tyrant (kills Thomas), declares war on nature (massacres the seagull) and literally mounts mysticism and tradition. Finally, this man reaches his goal and rises (hardly creeps up in his bloody-shitty rags) to the light from where he instantly falls deep, his glorious victory turns into slow agony while his body is torn apart by the seagulls and in his impotence he can do nothing but silently disappear in the gastric of nature per bite. I have to stress the fact, that the final scene jolts the viewers out of the film, as we do not see what Winslow sees (the light in its totality) but how he reacts to it, then in the last composition our hero is not looking at us but he is blankly staring into the void. Clearly, this gesture was meant to evoke a form of identification between Winslow and the viewers, since both of us are left dissatisfied in a certain sense.

Jerking on the Waves of Love

This destruction happens under the enchantment of the lighthouse, an undeniably phallic symbol. Its mystique is more enhanced by the Freudian interpretation which states that the locomotives of human life, our drives, should be divided into two groups: the pleasure principle and the death drive (Freud 2003). Our characters’ (civilizational) deterioration is well exemplified by the fact that the same duality is working inside and between them, since there are two contradictory ongoing forces that are, as Kyle Derkson well-articulated it, based on intimacy. Although, Derkson considers it as “The one shared social norm between them is that they must not be intimate with one another.” (Derkson 2019, 5) and that “Only when the two men are drunk is this rule blurred” (Ibid.), in my opinion the situation is a bit more complex than that. Instead of fading, I would rather call it a kind of pulsation that is present in the dynamics of the two characters, a pulsation that is based on the sadistic-masochistic relationship formed between them.

A good example of time happening without passing is that Thomas as an (ex-)sailor is sitting on a motionless rock. Moreover, while seafaring involves movement, Thomas’ job in this vast stillness is nothing more than looking after the very thing with the intended purpose of serving as a fix landmark from a distance for those whom he is not part of (anymore?). The movie, beyond making obvious Thomas’ “sailorlessness”, is even questioning whether the man has ever been a sailor. The possibility arises that Thomas is nothing more than a never was sailor’s simulation in bad faith.14 This possibility is of particular importance, because if we take into account that the sailor’s primary love is the sea, then it becomes clear that in reality every story from Thomas in this topic is about love, more precisely about its (heterosexual) object: women. However, in this regard Thomas is lying all the time. The two motifs are connected by the story of Thomas’ leg: first he says that he had broken it, so nuns took care of him and he fell in love with one of them but he had to leave the sea behind forever because of his crippled limb. Later on he brings up a story in which he and his companions had to eat grass without teeth because they got the scurvy, as the reason of leaving behind the life of the sailors, plus once he mentions his ex-wife and children as well.

His sincerity about his identity gets questioned in every case thereby.

The Lighthouse (Robert Eggers – The Lighthouse, 2019)

Boria Sax compares the mariners’ lives to a monastic order: besides the obvious differences in their lifestyle and education, both of them are communities separated from women and the outside world. Furthermore, they both have rich spirituality that seems unreachable for ordinary people (Sax 2000). We can call Thomas’ sailor identity a simulation, because despite he has never had anything to do with this way of living, if we agree on that suggestion of course, he could perfectly associate with the attitude itself and live exactly like someone who used to be part of the very thing that establishes this approach. In his case, the Baudrallardian idea about “the map that precedes the territory” (Baudrillard 2010, 1) actually becomes true.

One really important element of the previously mentioned mariners’ lifestyle also appears in Thomas’ character: vulnerability (Sax 2000). The man’s whole trauma is based on his defencelessness, the sea in both senses, so as nature and as the realm of the unconscious, carries within itself the obvious danger that the elements could drift him away and he could do nothing against it. This is the vulnerability that he transforms into sadism with a detour, and what Winslow, his current subordinate, turns to be the target of, whom he constantly humiliates and judges his every action, not to mention that he purposely crosses him, since he writes lies about him in the lighthouse’s “Holy Bible”, the work diary, which is a decisive component in Winslow’s payment. Winslow is an obvious threat to Thomas, and this threat, even if not consciously, is detected by the old man, their world order conflict eventually leads to the fall of both of them. That being said, I have to note that from the two of them it is Winslow who is trying to avoid these conflicts from the beginning (both with Thomas and with his own past) and tries to be present “as himself” for the least. He would not like to talk about himself, his life, as he would not like to put on the beliefs and rituals of “the old world” neither. Thomas “drags him into” the whole situation, like he would like to consciously bring his own death on himself with it as well.

The trauma of Winslow is multi-layered, but basically rooted in passivity as well. Freud is referring to this state as the “eternal recurrence of the same” (Freud 2003, 97), when someone repeatedly goes through similar things, like a romantic relationship, in a similar way, despite being passive in these situations. Winslow beared the terror from his shift supervisor just like he did from Thomas; moreover, the fact that he witnessed the death of his former boss wounded him forever, as now he feels like he became the perpetrator, a murderer due to his inaction. It is an accurate suggestion from Derkson that the conflict between the two men is based on the fact that Winslow refuses to follow Thomas’ superstitions (see the toast on the first night), then he starts directly facing the old man’s will (killing the seagull); furthermore, Thomas does not let him near the light while he also follows every step of him from the panopticon of the lighthouse (Derkson 2019).

Winslow’s reaction to this is, on the one hand, further isolation in the intimacy with the mermaid, or with her “totem” more precisely, on the other hand, the rebellion against Thomas’ superstitions by killing the seagull. His behavior unconsciously strengthens his passive, victimized position as he takes a bizarre, masochistic role. I have previously brought up this affair, both of them deal with an unconscious denial of the present15 sexual attraction between the two of them, that (I mean the attraction) both of them think is perverse.

The first act of the return of this denial is the incident involving the steak: “If I had a steak, I would fuck it” says Winslow and then Thomas, like a jealous housewife, first challenges Winslow about his own cooking, who does not hesitate to put his opinion to Thomas’ eyes, then in response, Thomas starts raving with fury and cursing him for nearly two minutes. Winslow’s erotic adventures are associated with the mermaid, of which once he thinks was intentionally hidden in his bedding by Thomas. Then when he overcomes Thomas during their brawl, for a moment he gets disconnected from reality and starts fantasizing about the coition with the mermaid.

Moreover, this is the scene that leads to a change of roles. It seems like the continuous pulsation, denial-returning, attraction-repulsion between them got so accelerated in this fight that seemed like a sexual act for a moment, that the two poles, the previously mentioned sadist-masochist roles swapped, resulting in tearing up the trauma as well. From now on, Winslow is treating Thomas like a dog, then even buries him alive, while he does not resist against it at all, but crawls on all four16 into his own grave pit instead, like we are witnessing the grotesque replay of the previously explained traumas. He only gives a long, myth-shattering monologue to his partner’s delight, one that I have written about in the beginning of my essay. That is momentary of course, after this scene the old captain returns for a final clash.

The Lighthouse (Robert Eggers – The Lighthouse, 2019)

I find it important to clarify what kind of traumas the film is dealing with. In my opinion, it makes it easier to understand what we saw, if we look at these traumas as a past that is sticking to the present without the intent to detach or tear off it, something that was unconsciously always there. Its specialty is that during the insanity demonstrated in the movie, the trauma becomes part of the naive experience of the present, which means for our heroes that their experiences are becoming a synthesis of real and unreal elements while these “components” are impossible to distinguish from each other. What I am referring to with the term “naive” is the fact that the whole experience of reality is not being questioned for a single moment. There is only one exception: the time when Thomas, for provocative reasons, brings up the idea to Winslow that the man actually killed his superior and everything that he has been through for the last couple of weeks (if they were weeks and not days or just minutes) is only the delirium of frostbite somewhere in the middle of nowhere in Canada. In this phenomenology lies the film’s surrealistic character: the clash of known and unknown is unfolding before our eyes in its artistic reality.

Even though, we can draw some parallels between the hauntology of the film and our heroes’ traumatized experience of time, these two phenomena are fundamentally different: once, while in the case of hauntology we are focusing on the thing that has happened in the past, here we are talking about the person whose experience is soaked in trauma, because of the phenomenon’s subjective nature; second of all, the ghost of the past could seem abnormal for the sake of conceptuality at most, because it is part of our everyday lives, while in contrast, this level of being traumatized and the insanity itself that brings all this to the surface can hardly be seen normal (this term meaning anything).

We can interpret it differently: if we accept that both Winslow and Thomas are the Human Being, but one is the archetype of the person before and one is the person after the Enlightenment, then the attraction between the two can be seen as if the whole process, “the rise of human spirit” was nothing more than the vain and narcissist attraction of Human Being to itself, a form of compulsive autofellation.

The Mermaid

The mythic figure of the mermaid is deeply rooted in cultural history. From the beginning, one of its recurring roles is to deviate men from their path and grab them out from their companions to lure and lock them to its mysterious realm (Sax 2000). Examining it from the aspect of the previously mentioned homoerotic attraction, the film resonates with Freud’s suggestion that when we are facing instincts or part of instincts that does not seem to be self-identical for us (so it seems like that they should belong to someone else, to a stranger, a not-me, an Other), then the process of repression cuts the way to satisfaction. If these repressed sexual instincts can reach satisfaction by a detour, then the self feels embarrassed for this success (Freud 2003). A good example of this embarrassment is when Winslow, after ejaculating, is collapsing while shouting and then breaking the little mermaid statue; moreover, later he is boasting about his destruction to Thomas, like he is proving the breaking of his spell.

“But let us remember that the seduction of the mermaid is generally to death. Perhaps this reflects the apocalyptic fears that have accompanied the rise of modernity” (Sax 2000, 52) – states Sax and this reading perfectly fits into what we have articulated before. Actually, the mermaid is luring Winslow into his doom and the light, that we can look at as a metaphor of Enlightenment or modernity as well, is nothing else but destruction. Who is following it is marching to decay, but the real sailors are not moving towards but navigating against it. However, Winslow was not a sailor, he was a lumberjack, with his dramatic death in the end of the movie he fulfils not only his destiny, but the curse of Thomas Wake as well, the curse he deserved for the criticism of his cooking (most importantly: his lobster).

The Lighthouse (Robert Eggers – The Lighthouse, 2019)

Sax identifies the mermaid’s traditional representation, as she is brushing her hair while being bewitched by her own portrayal, with the self-consuming characteristic of the consumer society (Sax 2000). I find this analogy quite appropriate, however, in the movie the mermaid appears as a representative of nature and as a form of transition. Being a stranger for myself is quite familiar for the Freudian way of thinking as well and this creature accurately displays this frustration with its own direct duality. This duality is a main problem of humanity as well, one of the ambivalences of its being is that it thinks about itself as something that is more or at least different from nature, while it is eventually part of it. In this sense, the mermaid in the movie with its seagull-like singing is luring Winslow to nature as his own unconscious, then he makes her as human-animal-myth-modernity his many times. In the end, it becomes clear that this conquest “mission” can only end with tragedy, nature will reclaim what belongs to it (if necessary, human beings themselves) and modernity will eat its children alive. Winslow vainly carries out a successful “revolution” against the past, defeats Thomas and reaches the light, in the end it does not lead to anywhere. The clash of Thomas and Winslow, what is to say the old man against the new man ended without a winner.

The Lighthouse (Robert Eggers – The Lighthouse, 2019)

Works cited

- Barrle, Thomas. 2020. “The Lighthouse’s obscure aspect ratio is no accident.” GQ. https://www.gq-magazine.co.uk/culture/article/the-lighthouse-aspect-ratio; downloaded: 2022.03.26.

- Baudrillard, Jean. 2010. “The Precession of Simulacra” in Simulacra and Simulation, Michigan: The University of Michigan, 1-42. trans. Sheila Faria Glaser

- Böhme, Hartmut. 2016. “A romok esztétikája” in Ókor, 2016/4. 79-86. trans. Verebics Éva Petra.

- Böhringer, Hannes. “Romok a történelmentúli időben.” trans. Tillmann J. A. in Nappali ház, 1990/01, 53-59.

- Buder, Emily. 2019. “Exploring the Stunning Black and White Cinematography of „The Lighthouse”.” No Film School. https://nofilmschool.com/lighthouse-robert-eggers-blaschke-interview; downloaded: 2022.03.26.

- Derkson, Kyle. 2019. “The Lighouse” in Journal of Religion & Film, 2019/2.

- Derrida, Jacques. 1994. Specers of Marx. trans. Peggy Kamuf. New York, London: Routledge. 1-60.

- Freud, Sigmund. 2003. Beyond the Pleasure Principle. trans. John Reddick. London: Penguin Books.

- Freud, Sigmund. 2010. The „Wolfman”. From the History of an Infinite Neurosis. trans. Louise Adey Huish. London: Penguin Books.

- Freud, Sigmund. 1963. “Introductory Lectures on PsychoAnalysis (Part III; 1916-1917)” in James Strachey, ed. The Standard Edition of the Complete Works of Sigmund Freud (volume XVI). London: The Hogarth Press and the Institute of Psychoanalysis.

- Hawking, Stephen. 2016. A Brief History of Time. URL: https://www.fisica.net/relatividade/stephen_hawking_a_brief_history_of_time.pdf ; downloaded: 2022.03.26.

- Kant, Immanuel. 2007. Critique of Pure Reason. trans. Marcus Weigelt. London: Penguin Books.

- Kiss Miklós. 2001. “Filmtörténet tizennégy részben (III.). Európai filmes avantgárd: expresszionizmus és szürrealizmus.” Filmtett – Erdélyi Filmes Portál. https://www.filmtett.ro/cikk/610/filmtortenet-europai-filmes-avantgard-expresszionizmus-es-szurrealizmus/; downloaded: 2022.03.26.

- Nemes Z. Márió. 2018. “Akvatikus románcok. Tengermélyi gótika” in FilmVilág, 2018/02.

- Pápai Zsolt. 2001. “Fekete alakok, sötét háttér előtt. A horror története 2/1.” Filmtett – Erdélyi Filmes Portál. https://www.filmtett.ro/cikk/662/a-horror-tortenete-2-1; downloaded: 2022.03.26.

- Reyes, Xavier Aldana. 2019. “Gothic and Cinema: The Development of an Aesthetic Filmic Mode” in Punter, David, ed. The Edinburgh Companion to Gothic and the Arts. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 395-405.

- Reynolds, Simon. 2011. Retromania: Pop Culture’s Addiction to Its Own Past. New York, Faber and Faber.

- Robinson, Tasha. 2019. “»It was a learning curve for everyone«: Robert Eggers on The Lighthouse’s tech experiments.” The verge. https://www.theverge.com/2019/10/18/20921056/the-lighthouse-robert-eggers-director-interview-behind-the-scenes-robert-pattinson-willem-dafoe; downloaded: 2022.03.26.

- Sax, Boria. 2000. “The Mermaid and Her Sisters: From Archaic Goddess to Consumer Society” in Interdisciplinary Studies in Literature and Environment, 2000/2, 43-54.

Notes

1Derrida’s Specters of Marx was originally released in 1993. In the first chapter of the book (Injunctions of Marx), he elaborates the idea that Marxism is present today as a kind of a specter. The term “hauntology” refers to a time out of joint when we experience the embodiment of something from the past in the present –a specter. (Derrida 2006, 1-60) ↩

2I am aware that the name Winslow is only an alter-ego of Robert Pattinson’s character and he is originally named Thomas Howard. Nevertheless, I find it easier to present my ideas if I refer to him by the name he uses in the film. ↩

3The first outrage is related to Copernicus, as the heliocentric world view enlightens the fact that we are not the center of the universe; the second one is due to Darwin as he ruined the idea of the divine creation. About this third he states the following: “But human megalomania will have suffered its third and most wounding blow from the psychological research of the present time which seeks to prove to the ego that it is not even master in its own house, but must content itself with scanty information of what is going on unconsciously in its mind.” (Freud 1963, 285) ↩

4The protagonist of Lautréamont’s infamous book (Les Chants de Maldoror). Although the book was written in the 1860s, the members of the surrealist movement “rediscovered” him for themselves and his work influenced many authors thereafter. ↩

5Poe simply being from the USA should not be an excluding factor in this sense, there are films of the German Expressionism that are based on his works, like Eerie Tales (1919, Richard Oswald) or The Plague of Florence (1919, Otto Rippert). ↩

6Freund was the cinematographer of films like The Last Laugh (1924) directed by F.W. Murnau; Fritz Lang’s Metropolis (1927); Berlin: Symphony of a Metropolis (1927) from Walter Ruttmann or Dracula (1931) that I am referring to in the main text and of which he is unofficially the co-director of as well. He directed some movies on his own is the 1930s, one of them are The Mummy (1932) or Mad Love (1935). ↩

7Physicists named the border of a black hole the event horizon and define it as “the boundary of the region of space-time from which it is not possible to escape, acts rather like a one-way membrane around the black hole: objects, such as unwary astronauts, can fall through the event horizon into the black hole, but nothing can ever get out of the black hole through the event horizon. (Remember that the event horizon is the path in space-time of light that is trying to escape from the black hole, and nothing can travel faster than light.) One could well say of the event horizon what the poet Dante said of the entrance to Hell: »All hope abandon, ye who enter here. «.” (Hawking, 2016, 89-90)

Nowadays it is still debated what would happen to us if we fell into a black hole. Most likely, approaching the center of it, time would pass more and more slower until we would reach a point where it would seemingly stop. The matter of my writing is still The Lighthouse and not the theory of relativity, however, I find this example quite adequate to describe the experience of time for our heroes. ↩

8I have made this statement based on the user reviews I have read on IMDb and on the Hungarian port.hu. This is obviously not a representative survey, I have only brought it up because I found these extreme reactions interesting and funny as well. ↩

9“In the age of crystallization only those things can crystallize that were formed before.” (Böhringer 1990, 55) ↩

10I am referring to movies like Through a Glass Darkly (1961), The Silence (1963) or Persona (1966). ↩

11The difference between a ghost and a specter, according to Derrida, is that the specter is materialized, embodied while the ghost is only a spirit without a physical body. ↩

12This statement is based on the acceptance of the Kantian thesis that space and time are the pure forms of our sensibility, so they are the basics of every sensible experience of ours. (Kant, 2007) ↩

13Winslow’s hallucinations are revolving around three returning figures. On his first night on the island, he is standing on the shore and watching the delirious Thomas in the lighthouse, then a floating corpse arouses his attention (it is later cleared that it is the body of his former superior). Winslow walks into the water and then submerges under the waves. After that, the mermaid is swimming towards us (towards the camera) while we hear her gruesome scream. The scene ends with Winslow waking up the next morning. ↩

14I refer to the Sartrean term as a synonym for self-delusion. ↩

15It makes no difference from the aspect of the interpretation whether it is brought to life by the situation or was always present before. ↩

16Freud deeply analyses a copulation in this pose and its possible homoerotic connotations in one of his other works, The “Wolfman” (Freud 2010). ↩

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.