1. SOUTH PARK: A BRIEF SURVEY ON A POSTMODERNIST ANIMATION

With a streaming activity of over three decades, South Park has the reputation of one of the most famous animations produced in the United States and transmitted worldwide, reaching an overall approval score of 8.7/10 and a 91 out of 250-rank in a top which celebrates the best TV shows, presented by IMDb (Internet Movie Database). Although mainly shaped with the purpose of entertaining audiences, South Park is famous due to its distinctive traits among American sitcoms, with features deeply rooted in postmodernist ideology due to the use of devices such as irony, satire, parody, perspectivism, metatextual tones and intertextuality. The use of these devices has the purpose of disapproving and ridiculing a series of social aspects, politicians, celebrities, films and other media categories, religions, plus relevant events and tendencies.

South Park is a collection of postmodernist animated narratives which develops satirical and parodic discourses throughout its twenty-four seasons. Aired throughout three decades, Trey Parker and Matt Stone’s project has changed its status from an underground animation (passed from one person to another for fun) to a mainstream media cultural product. Although part of the popular media, South Park takes up a different approach and roles in comparison with other shows of its kind, for example, by being critical of other narratives at work and by applying self-criticism. The first part of this article introduces the reader into the universe of the South Park series and presents some analysis starting points by building on the works of researchers and editors such as Robert Arp (2007), Jeffrey Andrew Weinstock (2008), Brian Cogan (2012), along with an interview provided by Steve Kroft and various media platforms. These researchers and their fellow scholars provide various insights into the richness of South Park’s narratives, exposing a series of tendencies and philosophies of the authorial persona and the finite representations provided in each season. The second part of my text presents the series-proper and has the purpose of offering insights about the South Park audiences and fan base in the United States and Europe (with a focus on the United States and Romania), while the third part of this article presents the purposes of the series, its coming-into- being and gradual development by defining details about the series by providing an analysis on South Park’s creation timeline, tracing its parcourse from an underground commodity to a worldwide phenomenon, along with summarising and introducing details regarding the plot, settings, leading and supporting characters of South Park.

In a joint study (2008), editor J. A Weinstock and twelve other researchers portray in-depth analyses of South Park from a variety of perspectives, having in mind the purposes of revealing aspects such as the series’ political stances, its involvement in a wide area of critical representation and the results in this sense (history, religion, politics, ideology, race, ethnicity, media). By analysing the events which mainly resolve around Eric, Stan, Kyle, and Kenny, the researchers agree that South Park parodies and satirises every aspect of human existence, even its own characters (Weinstock, 2-3). Their approach on sensitive subjects of the American society and not only has attracted many attempts to stop the show from running or to remove it from Comedy Central. At the beginning of its serialisation (and now as well), South Park has often been treated with discontent, while some of these anti-South-Park activists asked for the show to be banned because the animation is “dangerous for democracy” (Martin in Weinstock 3, see Peggy Charren’s plea). Responses like the one just mentioned sprung from the series’ relentless shock humour and its intent to push the boundary of representation and criticism. As such, South Park‘s status as an animated narrative offers it more freedom in terms of making use of parody, satire and inserting intertextual undertones throughout every episode. According to Sturm, the animated shape of South Park allows more limits to be broken (Sturm in Weinstock, 212). In this sense, taking into consideration South Park’s depiction of celebrities and other public figures, the series pushes the boundaries of real-life parody and satire further and insists on questioning the acceptance of celebrities. The series pushes these boundaries by using the following two means/freedoms: the episodes are not limited to real life, and the use of irony does not allow recelebrification (Sturm in Weinstock, 212-213). The sitcom’s political stance is also rendered in an interview with the two South Park directors, an interview guided by Steve Kroft. Even though the political approaches taken by South Park cannot be categorised, Steve Kroft indicated that the series learn towards libertarian views (CBS News, 11:15-11:33).

Furthermore, in a world where language is reshaped by factors such as political correctness, South Park offers a different/a more accurate perspective about the language spoken in America by having four nine-year-old children as protagonists of the show. In terms of language, Parker and Stone satirise the overuse of political correctness and reveal that they desire to convey a manner which is faithful to ‘how kids talk’ (CBS News, 8:56-9:12) – as other shows portray aestheticised forms of language. While giving an interview to Steve Croft in the wake of their award-winning musical The Book of Mormon, Trey Parker and Matt Stone provide some other clues in terms of deciphering South Park and their philosophy of creation. According to the two directors, executives and voice-actors of most of the South Park characters, Parker and Stone indicate that one of the series’ objective is that of challenging the current state of animated sitcoms and providing the viewers with something original and new (CBS News, 3:20-3:27). When asked if there are any limits to the subjects they represent throughout their American and worldwide sensation, the two give a precise answer simultaneously: “NO” (CBS News, 3:38). Besides, this interview highlights their strong cooperation even when disagreements appear. Their sense of humour, the key of their long friendship and collaboration, is a result of their compatible sense of humour and combining of satire, parody in their hardcore/strong sense of somewhat weaker form.

In a South Park-based compilation study, the editor Robert Arp and twenty-two researchers (2007) explore Trey Parker and Matt Stone’s explicit representations of relevant societal and political matters inside and outside of the United States by giving a more philosophical account on the tackled subjects. In accordance with this, the study combines philosophical thinking with popular culture, politics, ethics, religious studies, artificial intelligence, and explores, among other issues, the power of satire to challenge and reflect on power relations, identity, the educational system, representation, speech, law and democracy. In addition, it acts as a comprehensive dictionary of South Park, enveloping the deeper meanings of the series and relating them to viewers. Robert Arp indicates that South Park’s approach on specific issues mentioned above may make people feel uncomfortable and take a judgemental attitude. Even so, Arp indicates that South Park’s adopted stance (i.e., that of challenging past or contemporary discourses at work), is what makes South Park a relevant “voice” to take into account. In this sense, the characters and events depicted in the series have roles in disturbing the viewer and in starting a discussion (Arp, 2). As such, South Park offers its viewers a “healthy type of scepticism” (according to Robert Arp and Kevin S. Decker, 2): the viewers cast a sceptical gaze upon the representations and on themselves, thus contemplate about specific issues and engaging in discussions in hopes of improving the satirised, parodied topics of discussion.

In a collective study edited by Brian Cogan, scholars indicate South Park’s status as a serious-analysis piece, namely due to its resourcefulness of representations and meaning. According to Cogan (2012), South Park is an animated discourse worthy of analysing thanks to its richness of meanings and representations. Due to the vastness of subjects debated in a more pleasant or less humorous tone, South Park gains the status of a “transgressive institution” (Cogan, vii; x). What is more, Cogan indicates that South Park sometimes adopts political views specific of the left and right but does not pose an explicit political stance on any of them. Indeed, the sitcom’s approach on political view could be regarded as libertarian, by manifesting values of the right or left, being critical of both (Cogan, xii). Throughout the same study, Cogan repeatedly highlights the show’s ability to surprise audiences and to be a resounding transgressive discourse of American television. South Park often strives to expose subjects, themes, events or characters belonging to the marginal and the dominant and subverts/deconstructs both. By tackling various issues in the American society and the world, the South Park may hint at challenging assumptions, stereotypes, debates which may be considered as too problematic to be discussed in today’s society (Cogan, xiv).

2. SOUTH PARK’S CHARACTERS AND PLOT WITH A DETOUR ON A EUROPEAN/ROMANIAN PERSPECTIVE

As the series started to become popular since its first airing on Comedy Central, South Park has an extensive manner of reaching audiences outside of the United States of America. Not only is the series famous in the United States, but it is also easy to grasp for those who live outside the borders of the United States. This endeavour is possible due to the policy of South Park Studios concerning the series’ free display of each episode on the official South Park Studios site (available at the following address: https://southpark.cc.com/full-episodes).

In Romania, for example, South Park can be viewed on Comedy Central and by accessing the site mentioned above. On TV screens, South Park first aired an episode on Comedy Central in 2013. Although famous among viewers, South Park can encounter certain resistance in terms of audiences from European countries mostly because of their sometimes too explicit manner of portraying ideas and characters. While some take South Park too seriously and grasp the literal sense of the cultivated narratives, tehre are certain countries which have banned specific episodes. One such example is provided by Romania’s take on the Jewbilee episode. According to the South Park fandom, at the dawn of the 2000s, the CNA (translated as National Audiovisual Council) prohibited the transmission of the Jewbilee episode on the grounds of antisemitism (South Park Fandom). Nonetheless, the episode is currently available in Romania, with the mention that other episodes directly satirise some issues of the Romanian society in a highly offensive manner but have not been banned (see the Quintuplets 2000). Along with the official South Park site which provides the full episodes, other platforms which include the whole series of South Park (together with its film versions as well) are Netflix, Hulu, HBO Max and Amazon Prime.

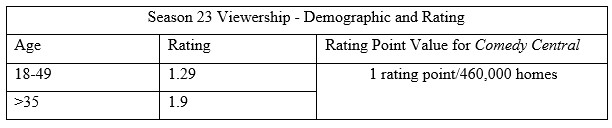

The four-time Emmy awarded series has managed to attract global audiences since 1997. Although the show has been popular since season one, its fame rises more with each season and shows a broader and increasing interest in the diverse comical and satirical representations guided by Stan, Kyle, Eric and Kenny. In terms of linear TV viewership, Comedy Central registered an all-time high viewership for the show in 2019. The TV platform claimed that South Park fans watched 30 billion minutes of the series, an all-time high-audience registered on TV for Parker and Stone’s animated series, without including the minutes viewed on online streaming platforms (Porter). The episodes which belong to the most recent season of South Park, namely Season 23, each claimed 1.4 million views, thus being the most popular among audiences between 18-49 (Porter). In the Table 1 below, one can observe that one rating point for the above-mentioned TV channel values 460,000 homes/per rating point (Carter).

Table 1.

As portrayed in the table above, the rating points registered on real-time television on Comedy Central claims a 1.29 rating point among viewers aged 18-49. For the same season, viewers of under 35 years old claim more rating points than the 18-49 age group with a 1.9 to 1.29 difference (Porter).

Before becoming a world-renowned show, South Park started as a humorous taped commodity made of paper clips in 1992 by Parker and Stone, two colleagues at the University of Colorado, who were interested in film production and studies. The initial creation entitled Jesus vs Frosty gets redone in 1995 as a video-request from a Hollywood executive, namely Brian Graden, and bears the name of The Spirit of Christmas or Jesus vs Santa. The Christmas card is initially meant to be passed around in small circles in America but rose to fame by being passed around by celebrities in their circles (George Clooney, for example), and the remake becomes the genesis of the show and started (Weinstock, 7). Trey Parker and Matt Stone revealed that the pilot episode The Spirit of Christmas was projected for fun and send via disks to various people in America, securing them a contract with Comedy Central. Thus, the animation changed its status from a marginal or subcultural artistic production to one of the most popular animated sitcoms.

As for the setting of the animated sitcom, one city which is often connected with the animated city of South Park is Fairplay, mainly due to its museum entitled “South Park City Museum,” situated at the western side of the town. The “South Park City Museum” is an outdoor history museum which brings to life a former mining camp. Even so, the depicted actions do not revolve around a real city entitled South Park. While some link the primary setting of South Park with a city which bears the same name as the show, Trey Parker and Matt Stone did not link the city depicted in the series with an existent one in the state of Colorado (McKee). What the two makers mention is that they chose existing destinations which are found at the outskirts of Colorado. The strange rumours going on about South Park, such as the presence of UFOs (Carter) inspired the two to create a setting in which they could be critical of various American and non-American issues and characters (CBS News, 3:00-11:02). As a fictional city with inspiration from real-life American towns, South Park is portrayed in the centre of cities such as Fairplay, Como, Breckenridge and Harstel (McKee). In the series, the fictional town of South Park is found at the base of some mountains in Colorado. The most prominent places in town are the South Park Elementary School and Kindergarten, the Townhall, downtown, the underground and the various houses of the main characters Stan, Kyle, Eric and Kenny.

Outside of South Park and the state of Colorado, the series bases their actions in fictionalised places inspired from real destinations in the United States. The most recurrent settings portrayed in South Park are Washington DC, New York, California, Florida, and Hollywood. Besides these locations, places outside of the United States are also depicted, mainly Canada and Mexico, along with others such as Germany, Romania, Japan, Denmark, Russia, the United Kingdom, China. In other episodes, the setting shifts to realms inspired by religions such as Christianity, Buddhism and Islam. Taking into consideration the (reinterpreted) depiction of Heaven and Hell, it is noteworthy to mention that the boundaries between the human world and the ones in which gods reside are intertwined. In this sense, Jesus is a permanent resident of South Park and God appears in the United States after being summoned by Jesus (at the request of the South Park citizens), while Satan briefly comes out of Hell, and Kenny, one of the four main characters of the show, is a simple human, who often visits the realm of Satan.

The series follows the actions of four children and friends, namely Stan March, Kyle Broflovsky, Eric Cartman and Kenny McCormick. The four children, aged between 8-10 years throughout the show, are permanent residents of South Park and students in the third grade and then fourth grade at the South Park Elementary School. Throughout its 25 seasons, the show’s floating timeline and the sometimes-inconsistent timeline does not age the boys more than with two years old. Between the first and fourth season, namely the seasons which coincide with South Park’s developmental stage (Hugar), the boys are aged 8, while between the fifth and fourteenth season, which are part of the experimental period, the boys are aged 9. Starting with the fifteenth season and up until today, the boys’ ages vary between 9-10. The main characters employ a vulgar language, perceived to belonging to adults. The creators of the show indicate that their very use of language contradicts this assumption: Stan, Kyle, Eric and Kenny talk like children (CBS News, 8:56-9:12) and their use of vulgarities reinforces the taboo value of their discourse. Although their language is sometimes vulgar and includes swear words, the children’s phrasings are full of witty responses, surpassing those belonging to adults.

Two of the four boys, namely Stan and Kyle, are the cartooned representations of Trey Parker and Matt Stone. Their friendship and collaboration of the two co-creators transcend the realm of real-life into cartooned versions. The two boys often disagree in certain situations with Eric Cartman, the big-boned and most mischievous character out of the 4, and the duo is in a close relationship with Kenny, the child who muffles his words because of his orange parka hood which covers his mouth. In the animated series, Stan and Kyle complete each other’s thoughts and reinforce each other’s views, as the two creators do in real life. The first recurring motif of the series finds the duo point out that Kenny was killed by using comments such as: “Oh my God! They killed Kenny!”, uttered by Stan, while Kyle completes the remark by saying ‘You bastards!’. The most creative one, Stan, the animated alter ego of Trey Parker, is supported by Kyle, a Jewish boy who reassures Stan of his support and completes his theories and perspectives in the same manner as Matt Stone does for Trey Parker. Also, at the end of each episode, one recurring moment in the series consists of Stan and Kyle giving a moralistic view of the events unfolded in the half-an-hour episode. During their “You know, I’ve learned something today” section, the boys try to make sense of the actions depicted in the episode, be it a moralistic lesson or not, often triggering a humorous and introspective response for the viewers.

The fan-favourite of the quadruplet is Eric Cartman, a character inspired from Trey Parker’s childhood friend Matt Karpman (Comedy Central). While the boys usually address each other by using their first name, Stan, Kyle and Kenny address their mischievous companion by his family name. Cartman, is in a constant hero vs anti- hero dichotomy (with obvious leanings on the darker side) and finds himself at the core of wicked events, triggered or not by his contribution. Spoiled rotten by his mother, Liane Cartman, but with no father figure in sight, Eric can be labelled as the most outrageous character in the series due to his vocabulary, actions and evil mastermind. His evil-doings vary from selling candy to children in a get-healthy and lose weight camp to pretending to have a handicap to participate in a competition for physically challenged children while being healthy (his only problem is his overweight). What is more, Eric often finds himself reinforcing stereotypes about immigration, ethnicities and Jews, dressing up at Hitler and uttering anti-Semitic slurs for a school costume competition, bullying Butters and others of a higher innocence than him. His list of devilish deeds is topped by his intention and successful plan of killing Scott Tenorman’s parents in order to get revenge for being mocked at in the Scott Tenorman Must Die episode (2001).

The fourth member of the group and the most silent one, Kenny, is portrayed as wearing an orange parka hood which causes his voice to be muffled and not easily understood by audiences and people around him (his friends have no problems in deciphering what he says, nonetheless). His upbringing is not as fortunate as in the cases of his friends: while others have a good family situation, Kenny’s parents are alcoholics and are too poor to bring food on the table. The inspiration for Kenny’s character comes from Trey’s friend, an impoverished boy who absented classes. This absence would make the other children laugh about him being dead, which explains why the animated version of this child regularly gets killed in various situations throughout the series (Comedy Central). While his impoverished condition is the subject of many jokes and ironies, Kenny remains a positive presence throughout the series and makes the most explicit jokes. As Eric’s mischievous and sometimes evil actions cannot be overpassed in the series by any other character, Kenny beats Eric in terms of swearing and foul language. Kenny’s muffled voice makes it difficult for the audience to understand what his plea is, be it a funny joke or not. Although his presence is often sensed by his muffled voice or lack of voiced arguments, his presence, absence and constant re-emergence is central to the show’s narrative. One aspect tied with Kenny is his constant death and revival throughout many episodes. Since Kenny died in the pilot episode in 1992, but Brian Graden requests Kenny to be a part of the 1995-remake- video, the co-creators brought him back for The Spirit of Christmas (1995) and in the first season aired in 1997 (Weinstock, 9). Since then, Kenny’s death is an expected recurring moment for South Park audiences. Even if Kenny’s death is an anticipated outcome, Parker and Stone deconstruct the audiences’ expectations by sometimes leaving Kenny alive or by making him die more subtly or unexpectedly. As such, when audiences get comfortable around certain traits belonging to a character or expect recurring motifs in the plot, the co-creators break the rules of the audiences and trigger their displeasure (Weinstock, 9).

The actions depicted in South Park follow the daily adventures of the main characters, namely Stan, Kyle, Eric and Kenny, along with supporting characters such as “Leopold Butters” Stotch, Randy Marsh, Chef Jerome McElroy, Mr (Herman) Garrison, Mr Mackey, Officer Barbrady, Wendy Testaburger, Craig Tucker, Tweek Tweak, Liane Cartman, Timmy Burch, Jimmy Valmer, to mention a few. South Park constructs its narrative around the characters mentioned above and represents events which blend the real with the fantastic. In the universe of the series, the four children encounter ordinary people and inhabitants or non-inhabitants of their rocky-mountain town, celebrities (Michael Jackson, Kathie Lee Gifford, Tom Cruise, Paris Hilton, Britney Spears, Kanye West, Barbra Streisand), politicians (George W. Bush, Al Gore, Hillary and Bill Clinton, Donald Trump, Boris Johnson), along with deities (mostly Jesus and Satan), talking animals, personified objects such as Mr Hankey, Towelie and even aliens.

While the disclaimer posted at the debut of each episode denies any connection with real-life people (“All characters and events in this show – even those based on real people – are entirely fictional), the show does satirise real people and their actions. By using this disclaimer, the two authors avoid getting sued in court and gain the freedom of representation which is limited for real-life series since these elements can easily blend into a subversive cartoon. Upon mentioning these pieces of information, the reader should know that the provided summaries include depictions from episodes such as Pinkeye (1997), Quintuplets 2000 (2000), The Passion of the Jew (2004), Member Berries (2016), Oh, Jeez (2016), and Dead Kids (2018). In Pinkeye (1997), the seventh episode of its premiering season, Eric, a big fan of sweets, competes against other students in a costume competition whose prize consists in significant amounts of candy, a contest organised at South Park Elementary. With the eyes on the candy, Eric dresses as Hitler for the costume competition and is criticised for it by Chef and Principal Victoria. While he (forcefully) views an educational video, Eric does not get a coherent and fact-based explanation which could have explained why Hitler was not a good model. Because of the tremendous support the animated Hitler got in the video (an animation within an animation which represents the original Nazi rallies), Eric’s appreciation of the dictator grows stronger. With misunderstandings such as this one, the essence of the episode consists of deconstructed infamous characters and organisations, along with the process of satirising failures in parenting and flaws present in the educational system. This approach may serve as a way of questioning the the authority figures responsible for childhood education.

Stan, Kyle, Eric and Kenny get involved in a pursuit of keeping up with the forever evolving game industry and pursuing to catch all Chinpokomons in the Chinpokomon episode (1999). While the animation follows the intention of the Japanese to take over the world by manipulating the minds of children who play with Chinpokomons (an obvious parody of Pokémon), Chinpokomon is also a satire which forecasts the ephemerality of trends in gaming and the superficiality of children, adults and the practice of consumerism. Later on in Quintuplets 2000 (2000) the main plot focuses on how Eric, Stan, Kyle and Kenny are trying to rescue Romanian quintuplets from going back to their homeland, described as a poor and undesirable place to inhabit. While the boys try to introduce the quintuplet girls to malls and other distractions (while the girls remain nevertheless unimpressed) and seemilngly the narrative seems to be mocking at Romanians, this episode is intended to primarily satirize American society, its authorities and the sometimes-superficial protest culture. While Romanians and Americans want to take the girls back home and, accordingly, to keep them in the US, they do not ask for what the children genuinely want, but act upon what they believe to be the best choice. The same logic is applied to Kenny. He travels with his family in Romania to become a singer and, while he is the most impoverished child in his group of friends (and in South Park), and perceives that 200$ is a more-than-enough sum of money for living well in this eastern European country. While he is happy in his new home, the American authorities disregard his choice and his family’s desire and try to take him to the United States forcefully.

Another highly satirical part of the series is The Passion of the Jew (2004), one of the South Park episodes which uses The Passion of the Christ as a background trigger to satirise Mel Gibson, guilt, Adolf Hitler and the American public’s ignorance. Upon watching The Passion of the Christ at the cinema, Eric feels entitled to mock his Jewish friend, Kyle, for the crime that Jews had committed: they killed Jesus Christ and, thus, are evil. With a feeling of building guilt, Kyle blames himself for what happened and declares that Eric can rightfully accuse Jews of being evil. In addition, Eric proceeds to fix the errors of the past by cleaning the present from evil, i.e., Jews. By dressing as Adolf Hitler, Eric leads a mob who chants anti-Semitic slurs (the crowd chants the slurs in German and they are ignorant of their meaning in English). The crowd members do not recognise Eric’s portrayal of the Nazi leader and believe that they are chanting in Aramaic, the language used by actors in the movie they all viewed at the cinema.

In terms of politics, South Park adopts a critical stance towards both the dominant parties in the United States for their poor handling of the 2016 Presidential campaign. While mocking at the 2016 election campaign and its aftermath, season twenty depicts parodies of candidate Hillary D. R. Clinton and Donald J. Trump (portrayed initially by Mr. Garrison). In the first episode of the season, Member Berries (2016), Mr. Garrison (portraying Trump’s role) picks Caitlyn Jenner as his running mate and try to secure the elections. While having second thoughts, the Republican candidate hopes to make Hillary Clinton win in a less obvious way since he is aware that he does not have the necessary experience to become the Chief of the state, an intention which he utters in their presidential debate. Since Clinton fails to grasp this opportunity, the result of the election secures a Republican President at the White House, but not by highlighting a Republican success, but a Democrat or Hillary Clinton defeat. The turnout which was not expected by the co-creators of South Park, resulted in a change of narrative for the next serialised episodes shortly after the official results came out (Miller), depicted in the Oh, Jeez (2016) episode.

Furthermore, in Dead Kids (2018), the boys are caught up in a problematic situation which portrays a current American issue: gun control and school shootings. The entire plot reflects how overexposure to tragedies can numb people and make them indifferent in the face of atrocities: the only one who is outraged and worried about the school shooting taking place at South Park Elementary is Stan’s mother, Sharon. The children and other parents, the professors and the authorities view this situation as a regular part of their lives (in the background dominated by bullets, one professor continues to teach his lesson, undistracted by the unfolding of events). In addition, this episode also mocks at the superficiality which the press tackles a serious issue: one reporter fails to understand how the children perceive the situation and increases dramatism by mentioning that the boys are distressed because of the shooting. In reality, the animation contradicts his claims as the shooting does not affect them in any manner.

In terms of narrative structure, the typical South Park episodes starts from a simple event which evolves as a snowball when triggered by a decisive or insignificant motif. A regular depiction of events follows the logic of a “therefore” or “but” scheme which ties the narrative of the story and makes it coherent. This procedure ensure the avoidance of thoughtless randomness.

3. CONCLUSION

Considering the arguments and pieces of information put into context and analysed throughout this article, South Park seems to have a very good trajectory, evolving from a low-budget private production with the traits of an “underground bootleg obsession” (Marin qtd. in Weinstock, 7) to a worldwide famous cut-out animation. Although its simple aesthetic seems to point out its plainness, the series depicts a complex variety of pressing issues which are controversial and whose representations may trigger (shock) humour, introspection and change due to their abundant use of satire, irony, parody and intertextuality. Its main characters, who are third and then fourth-graders, display a series of complex personalities and, although they do have core traits bind to them, their actions do employ conflicting results as initially expected (in order to surprise and defamiliarise the viewers). The animated versions of Trey Parker and Matt Stone, Stan and Kyle, highlight their strong friendship throughout the series and are often the voice of reason, sometimes seconded by Kenny. Eric sticks to his mischievous behaviour and is often at the core of whatever ill-intentioned events, trying to coerce the boys and other characters (such as Butters) into participating in his deeds. The most silent of the four characters because of his muffled voice, Kenny, does provide a pinpointed commentary to specific issues (the most talkative is Eric). In addition, Kenny is a powerful presence throughout the series, even if he is killed and brought back regularly in different episodes.

As portrayed above, South Park adventures revolve around moral and somewhat immoral teachings which are wrapped around in layers of subversive humour, irony and (social, and political) satire. Nonetheless, the show does have certain parts or episodes which have lesser hidden meanings and are intentionally illogical or wicked for wickedness sake, as a veritable postmodernist work (Hossain and Karim, 180). In this sense, by being defended by its “just a cartoon” status (Sturm, 212), South Park gains more freedom of expression in achieving its purposes of applying a critical gaze on contemporary issues and asserting self-criticism. As a result, South Park ’animates’ its status as a postmodernist work, responsive to both past and current events in and outside of the American borders, as portrayed in the briefly presented summaries involving the following episodes: Pinkeye (1997).

Works Cited

- Arp, Robert. 2007. South Park and Philosophy: You Know, I Learned Something Today. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing Ltd.

- Arp, Robert, and Decker, Kevin S., Eds. 2013. The Ultimate South Park and Philosophy: Respect My Philosophah!. Wiley.

- Carter, Bill. 1997. “Comedy Central makes the most of an irreverent, and profitable, new cartoon hit”. NY Times, 10 Nov. 1997. https://www.nytimes.com/1997/11/10/business/media-broadcasting-comedy-central-makes-most-irreverent-profitable-new-cartoon.html. Accessed 5 May 2021.

- CBS News. 2011. “Parker & Stone’s subversive comedy”. YouTube, CBS News [Online], 26 Sept. 2011. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0KppaxFfPNw&t=634s. Accessed 5 May 2021.

- Cogan, Brian. 2012. Deconstructing South Park - Critical Examinations of Animated Transgression. Plymouth: Lexington Books/

- Chinpokomon. 1999. [Online]. Directed by Trey Parker and Matt Stone. US: South Park - Comedy Central [Viewed 10 Jan. 2020]. Available from Amazon Prime.

- Comedy Central. 2020. “DID YOU KNOW THE SOUTH PARK CHARACTERS ARE

- BASED ON REAL PEOPLE?”. Comedy Central UK. https://www.comedycentral.co.uk/news/did-you-know-the-south-park-characters-are-based- on-real-people. Accessed 5 May 2021.

- Dead Kids. 2018. Directed by Trey Parker and Matt Stone. US: South Park - Comedy Central [Viewed 20 Mar. 2021]. Available from Amazon Prime.

- Hossain, Dewan Mahboob, and Karim, Shariful, M.M. (2013). “Postmodernism: Issues and Problems”. Asian Journal of Social Sciences and Humanities. vol. 2, no 2. Oyama: Leena and Luna International. ISSN: 2186-8484.

- Hugar, John. 2017. “The Five Stages of South Park”. Vulture.com, 11 Aug. 2017. https://www.vulture.com/2017/08/the-five-stages-of-south-park.html. Accessed 12 June 2021.

- Member Berries. 2016. Directed by Trey Parker and Matt Stone. US: South Park – Comedy Central [Viewed 20 Mar. 2020]. Available from Amazon Prime.

- Miller, Matt. 2016. “South Park Re-Wrote Tonight’s Episode for a Trump Victory”. Esquire.com, 9 Nov. 2020. https://www.esquire.com/entertainment/tv/news/a50524/south-park-presidential-election- trump-win/. Accessed 01.06.2022.

- McKee, Spencer. 2019. “11 real South Park locations you’ll find in Colorado”. Gazette.com, 25 Jun. 2019. https://gazette.com/arts-entertainment/11-real-south-park-locations-you-ll-find-in-colorado/article_1a7e1346-f1cd-11e8-924a-db564c6d2939.html

- Oh, Jeez. 2016. Directed by Trey Parker and Matt Stone. US: South Park - Comedy Central [Viewed 20 Mar. 2020]. Available from Amazon Prime.

- Pinkeye. 1997. [Online]. Directed by Trey Parker and Matt Stone. US: South Park - Comedy Central [Viewed 20 Apr. 2020]. Available from Amazon Prime.

- Porter, Rick. 2019. “South Park Viewers Watched 30 Billion Minutes of Show in 2019”. Hollywoodreporter.com, 17 Dec. 2019. https://www.hollywoodreporter.com/live-feed/south-park-viewers-watched-30-billion-minutes-show-2019-1263298. Accessed 16 June 2020.

- Quintuplets 2000. 2000. [Online]. Directed by Trey Parker and Matt Stone. US: South Park- Comedy Central [Viewed 15 Jan. 2020]. Available from Amazon Prime.

- SouthParkFandom.com. (2022) “Censorship in South Park”. https://southpark.fandom.com/wiki/Censorship_in_South_Park. Accessed: 20 Sept. 2022.

- The Passion of the Jew. 2004. Directed by Trey Parker and Matt Stone. US: South Park – Comedy Central [Viewed 20 Jan. 2020]. Available from Amazon Prime.

- The Spirit of Christmas. 1995. YouTube, Victor K. [Online]. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OBDA6oAorPw. Accessed 19 Jan. 2020.

- Weinstock, Jeffrey Andrew. (2008) Taking South Park Seriously. New York: State University of New York Press.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.