Introduction

The First World War and the peace treaties occupy a prominent place in today’s public and scholarly discourse. It is especially true for Hungary and its neighbours at the 100th anniversary of the Treaty of Trianon. This paper looks at British perspectives on the development of the Hungarian post-war settlement and the Treaty of Trianon by analysing contemporary primary sources, including press publications, general works on diplomacy, political speeches and memoires, to better understand not only the changes in the political discourse but also the motivations of the historical figures concerned. The article is designed to study their influence on the Paris Peace Conference and the post-war settlement with regard to Hungary as well as the trajectory of these opinions and policies with respect to Hungary. It is argued that the Trianon Treaty was not only the result of political instability in Hungary and the Carpathian Basin in general as well as the validation of the Great Powers’ political interests on the continent, which proposed to impede German expansionism and Russian Bolshevism, but also the result of the more effective propaganda activity of the anti-Hungarian group of British political activists and their international network led by Wickham Steed and Seton-Watson.

Before and during the First World War anti-Hungarian and pro-Slav voices became dominant and the pro-Hungarian politicians and intellectuals could not make their standpoints accepted as successfully as the pro-Slav activists. The most important reason for this was that the pro-Slav French and British activists built a closely-knit international network to downplay and eventually disintegrate the originally pro-Monarchist bias, especially in Britain (Cora 7–32).1 French political and public figures showed the least pro-Hungarian attitudes; almost all of the French politicians, activists represented a pro-Slav and anti-Austro-Hungarian standpoint. It is worth noting that the integrity of the Monarchy played an important role in British and French policy (at least in a federalised or a trialist form) until it met their interests as great powers (using Austria-Hungary to balance German expansionism, stabilising the East-Central European region, etc.). However, when they realised that the Slav nationalist groups, fighting for their own nationalist aims, could better serve their interests as great powers, most of them realigned their strategies and rhetoric in relation to the Monarchy (Cora 19–31). In 1916 Robert Seton-Watson, one of the main pro-Slav protagonists, published his work, German, Slav and Magyar, in which he disseminated his ideas about the “ethnic tyranny” of the Hungarians that became a commonplace in later discussions on pre-war Hungary.2

The pro-Slav British and French lobby groups had similar views on the future of Hungary. These groups mutually monitored and reflected on the activity of one another, so many of them, who participated in the delegations or were trusted advisors, arrived at the peace conference with quite complex yet clearly informed opinions about the desired post-war settlement that they wanted to realise as chief advisors of their respective leading politicians.3

British politicians traditionally regarded the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy as one of the pillars of European stability. However, the political crisis in 1905–1906 clearly showed the deficiencies of the Monarchy’s political system, as a result of which such political activists as Seton-Watson or Wickham Steed began to search for alternatives that could replace the Habsburg-dynasty in providing stability in East-Central Europe. Nevertheless, the dissolution of the Monarchy was not an option for them prior to the war; they rather wished to see the political reforms, especially democratisation, of the Monarchy, with the Slav nations invested with political autonomy (Arday 8, Steiner 70–82, Jeszenszky 80–96, Péter 439–446).

At the time of the outbreak of the Great War, Steed and Seton-Watson radicalised, and in order to support the endeavours of the Slav nations, they started to forge evidence and to consciously misinterpret political and social developments. For example, when the political elite of Hungary used cruel methods to quench potential rebellions, it was represented by Steed and Seton-Watson as the method of viciously suppressing the nationalities (Beretzky 19–20). Or, when the electoral system introduced to preserve the integrity of the Hungarian Kingdom was shown to be a system that suppressed the votes on the basis of the voters’ national belonging (Scotus Viator 392).

However, Steed and Seton-Watson had some opponents who supported the Hungarian viewpoint: Arthur B. Yolland was a pro-Hungarian intellectual and political actor who gained Hungarian citizenship, learned Hungarian and taught at Hungarian universities (Jeszenszky 90–95, Frank 99–113, Cora 14–19). Yolland was among the few British who truly supported the Hungarian cause and called attention to the web of distortions propagandists tried to cast.4 James Bryce, the famous British traveller, was not a rabid pro-Hungarian propagandist, but in his itineraries and travel books he depicted a rather peaceful image of everyday people’s lives.5 For example, according to Bryce, the Slovaks and the Hungarians lived together harmoniously, and neither the Slovaks, nor the Hungarians wanted to assimilate to the other (Bryce, VIII–IX). This statement is contrary to what Seton-Watson claimed in The Spectator, namely that the Hungarians treated the Slovaks tyrannically and wanted to oppress them.6

Wickham Steed and Seton-Watson had a much more extensive network of relationships in Europe and thus had more significant impact on both the European and British political and public discourse. Seton-Watson circulated propaganda films on the Serbs and distributed propaganda leaflets in British schools. In line with this, Steed participated at various conferences in France during which visits he deeply impressed French intellectuals and some politicians. His French colleagues like Jules Chopin or Ernest Denis, got to know the activities of British propagandists, and subsequently acknowledged and supported them. French Slavophiles were contended that their British comrades bore witness to similar views.7 However, it is still unknown in what kind of relationship British and French Slavophils had and how they could precisely impact on the course of the Paris Peace Conference. Did Denis or Seton-Watson personally know each other? Did Edvard Beneš act as a mediator between them? Did they consult to unify and better present their views at the conference?

Nonetheless, during the war, most of the British political perspective on Austria-Hungary rather turned to an anti-Hungarian stance due to the fact that anti-Hungarian propaganda in Great Britain operated far more effectively, unlike the pro-Hungarian one. In addition to this, the development of the military affairs, especially with the approaching and more and more perspicuous exhaustion of the Central Powers in the last two years of the war, obviously favoured the position of anti-Hungarians, too.

Hungary at the End of the Great War and the formation of British perspectives

In December 1916 Lloyd George and his five-membered war cabinet replaced the Asquith administration. Arthur Balfour was elected as the new foreign secretary. The new cabinet considered the issue of a separate peace treaty with Austria-Hungary. Thus, they initiated negotiations, which took place in Geneva between General Jan Smuts and the ex-Austro-Hungarian ambassador, Count Albert von Mensdorff, in December 1917. Smuts offered England’s advocacy and goodwill for Mensdorff if the Monarchy disentangles itself from Germany and forms a new, liberal and federal state which gives franchise to the nationalities. The British government argued that a federal Monarchy would resist a German expansion better than a dismembered Monarchy. In 1918 Lloyd George made it clear that he had no intention to dismember the Monarchy, he only asked for democratic self-government for the nationalities. In March 1918, as their final answer to the British peace-proposal, Austrians chose to uphold the German alliance (Jeszenszky 303–305).

After the failure of the negotiations, the British government changed tactics. They entrusted the British press baron Lord Northcliffe to set up a propaganda team to attack enemy countries. Northcliffe appointed Steed and Seton-Watson as the heads of the team to contribute propaganda against Austria-Hungary. Therefore, they could now campaign with official support and increased prestige for the Monarchy’s dismemberment and national ambitions for independence. Their strategy, suggested by Steed and Seton-Watson, “outlined a new policy, which included the breaking of Austria-Hungary’s power by supporting and encouragement of every anti-German and pro-Entente nation and tendency” (Jeszenszky, 306).8 This strategy aimed at raising nationalities against the Monarchy on the battlefields as well. Leaflets were distributed among the Austrian-Hungarian forces, which propagated Czech and Yugoslav independence programs, advocated by the Entente governments, and presented new borderlines. These leaflets called the soldiers for deserting the army and they were also invited to join the Entente forces (Jeszenszky, 306).

Seton-Watson and Steed established The New Europe, which was a journal that embraced different thinkers, politicians, historians and other influential people who were against Austria-Hungary and its two leading nations, especially against the Hungarians, and wanted to dismantle the Monarchy. The journal was first published in October 1916. What is more, it was a sound forum for the politicians of the nationalities of the Monarchy (Magyarics 3).

At the beginning of 1918, the Political Intelligence Department was established in the Foreign Office. The majority of the members was from the circle of The New Europe, such as Seton-Watson, Steed, Alan Leeper (member of the Smuts mission, along with Eyre Crowe), Harold W. Temperley (British Historian who later participated at the Paris Peace Conference). In addition, Seton-Watson was appointed as the leader of the Austro-Hungarian division of the Department of Enemy Propaganda. Even if the British government was not directly responsible for the dismantling of Hungary, but it accelerated this process. Nonetheless, contemporary British leading politicians allowed minor pro-Slav, pro-Romanian and anti-Austria-Hungary political groups in the Foreign Office and in the press to accomplish the rearrangement of East Central Europe (Magyarics 5).

Consequently, it can be argued that the dissolution of Austria-Hungary can be explained by two major factors. On the one hand, the culmination of the nationalist tensions within the state can be considered as one of these. The intensification of these tensions via the Entente Powers made the process of decline irreversible on the other. The Entente Powers took part in dismantling the Monarchy by signing secret treaties, entering into agreements with their allies and by promises made to nationalist leaders. The defeat of the Monarchy at war put an end to this process (Ormos 13–14). The newly founded Czechoslovak National Council was gradually accepted as the core of the future Czechoslovak government and then as an allied partner by the British government in September 1918 (Jeszenszky 307). Moreover, advocating the nationalities’ ambitions, which was also in accordance with President Wilson’s declaration, seemed a good remedy for the spread of Bolshevism. Also, it served as an answer to the charge of annexation. The Monarchy finally laid down arms in October 1918.

One of the reasons that revolutions could appear was that the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy was dissolved: on the 16th of October, 1918, King Charles IV declared Austria a completely independent state from Hungary (Gergely and Pritz 14). The separation from Austria was one of the very first issues that needed to be solved in order to have a chance at restoring Hungary after the First World War. After the separation, Hungary was also in need of a new constitutional framework, because at that point, it was a kingdom without a king. On the 16th of November, 1918, after the dethronement of Charles IV, the Hungarian National Council was set up to establish the principles of the new democratic political system (Gergely and Pritz 14).

Count Mihály Károlyi was elected as the president of the council, who intended to finish the war immediately and to initiate constitutional and political reforms (Gergely and Pritz 14–15). The need for change was the reason that even the soldiers who just arrived home from the front lines demanded a revolutionary change, which in turn led to the events of the Aster Revolution. On 30 October, 1918, the soldiers who were coming home from the front rose up against the old political system of Hungary (Gergely and Pritz 15–16). While it set out to be a revolt with guns, later it turned into a revolution and it gave the power into the hands of Károlyi and the National Council. Archduke Joseph of Austria, who was the regent of King Charles in Hungary, declared that Count Károlyi would be the Prime Minister of the country (Cartledge 47).

Károlyi still wanted to end the war, so he entered into negotiations with the leaders of the four great powers, France, Great Britain, the United States of America, and Italy, yet without success. As Bryan Cartledge emphasises, they thought that Károlyi was unable to create and control a democratic country, as Hungary was never democratic, and just a few months ago it was part of Austria-Hungary as a semi-dependent unit (Cartledge 52–53). In the meantime, while Károlyi wished to secure his place as the sole leader of the country, another politician of the old elite, István Bethlen began to organise a political movement in opposition to Károlyi. Bethlen founded the Christian National Union Party (Keresztény Nemzeti Egyesülés Pártja), which aimed at establishing a political platform for anti-revolutionary and conservative forces in Hungary against Károlyi’s politics. Among others, the party’s programme detailed how to settle into the world after the dethronement of the king and how to deal with the consequences of the war, for instance, the impending peace treaty (Cartledge 56–57).

After the Vix memorandum was received on February 26, 1919,9 which meant that a 40–50 km long zone would become neutral in order to ensure that Hungary would not threaten Romania (Bánfyyné et al. 18–19). Károlyi was forced to resign, because this neutral zone could not be rejected (Gergely and Pritz 24–25). Because of the fact that Károlyi could no longer fill in the position of the head of the country, as he could not approve any negotiation with the Romanian government, another party emerged to take control of Hungarian affairs. The Hungarian Social Democratic Party (HSDP) took over the governance of Hungary, led by Zsigmond Kunfi. After the HSDP and the Hungarian Party of Communists had united, Béla Kun was elected as the People’s Commissar for Foreign Affairs. On March 21, 1919, they declared that Hungary became a dictatorship of the proletariat (Gergely and Pritz 24–25). However, this form of government was not accepted by the Entente, or the successor states like Romania. Moreover, the governments of Romania and Czechoslovakia endeavoured to undermine the Hungarian military and political situation to turn the international reception of Hungary in their favour. These attempts were often illegitimate, for example, the Romanian army marched all the way into the heart of the country, as far as Budapest during the Hungarian-Romanian War of 1919 (Gergely and Pritz 34). After this move, it was not clear if Hungary could be restored at all, because there were many internal issues that hindered the political reconstruction of the country, including the question of who the new political leader would be or what changes would ensue in the political system.

Furthermore, Hungary was still in the period between the end of the war and the signing of a peace treaty, which meant that from a diplomatic perspective, the country was not considered as an independent one. Instead, this period was marred by political instability that is testified, besides the communist dictatorship of the Kun regime, by the sheer number of governments (Károlyi, Berinkey, Friedrich, Huszár, Simonyi-Semadam) (Gergely and Pritz 23–41). While these Hungarian governments did not serve long terms, as G. A. Finch, a contemporary American political scientist also observed, the short-term and instable governance was a considerable reason why the peace treaty could not be signed in 1919, because it hindered the peace talks as there was no stable political leader or body to negotiate with in favour of Hungary (159). While Hungary had to tackle with internal issues, including who would lead the country and what kind of political system should be established, in January 1919, after the armistices and the capitulations had been signed, the representatives of the Allied and Associated Belligerent Powers, as well as the Powers which had broken off diplomatic relations with the Central Powers met to decide the fate of Germany and its allies.

Diverging conceptions on the Hungarian borders within the British delegation

Before discussing the standpoints of the British delegation, it is worth examining how junior officers and political activists could increase their influence on the work of the British delegation. The reports from Vienna and Budapest were processed by the Western Department in the Foreign Office (Jeszenszky 88). Until 1905, the documents were transmitted to the competent ministers or the heads of the department without comments. The documents, which were judged more important, were printed and circulated in the government and foreign diplomatic missions. After 1906, a new system was introduced, so lower ranked clerks were granted the right to comment on these documents, thus relieving the burden of the minister. In consequence, the opinion of the competent head of a certain department became more important than the report of the diplomat on venue (Jeszenszky 88). The reason for that was the increased amount of diplomatic documents and a new generation who wanted to reform the Foreign Office, as the existing system became obsolete, and the formerly proposed reforms were insufficient.

However, these reforms in the structure and administration of the Foreign Office could bring about considerable changes in such a complex and delicate system of international relations at the turn of the century (Steiner 70–82). Because of that, many formerly unknown employees in the Foreign Office, such as George R. Clerk, Harold Nicolson, and, to a decisive extent, Eyre Crow gained influence over the issues related to Hungary (Jeszenszky 93). None of them were pro-Hungarian. Crowe did not particularly like Hungarians. Romsics claims that “Crowe too assessed the events [the Bolshevik Revolution in Hungary] as simple bribery and stamped as political ‘foolishness’ everything aimed at pacifying the bribers” (Romsics 2002, 93). Nicolson was rather indifferent towards Hungary in the beginning. He claimed after he had come back from a mission that the Bolsheviks in Hungary were not a serious threat (Doctrill and Steiner 76).

The Entente did not have a plan, a definite conception about what should have replaced the Monarchy. However, a highly efficient, pro-Slav propaganda team, led by Steed and Seton-Watson at Crewe House, submitted a modification of the peace treaties to the cabinet. Before this suggestion would have been accepted officially, Leopold Amery,10 a political secretary of the cabinet and one of Lloyd George’s advisors, had appealed to the Foreign Secretary, Arthur James Balfour in a memorandum, in which he emphasized that the procedure of the peace conference should be approached constructively and not from an anti-German point of view (Romsics 2005, 56). Concentrating only on appeasing the ambitions of the Entente Allies would lead to apprehension, obscurity and to another war (Jeszenszky 309–310). Amery emphasized that the realization of the suggested national states would be impossible and undesirable. It was impossible because there were no clear ethnic boundaries and it was also undesirable because the sole application of the nationalist principle would result in states economically incapable of existing. Instead, he suggested establishing a new Danube confederation, a superstate which included German-Austria, Bohemia, Hungary and which would have contained not only Slovakia but Transylvania, Bácska and Bánát as well as Yugoslavia and perhaps Romania and Bulgaria (Romsics 2005, 56–57). In such a community none of them would be independent but would have free scope to develop. Amery approved wartime propaganda and advocating the ambitions of nationalities as a necessary strategy for winning the war but these should be restrained at the final settlement in order to establish a supranational unity in Central– and South–Eastern Europe (Jeszenszky 311).

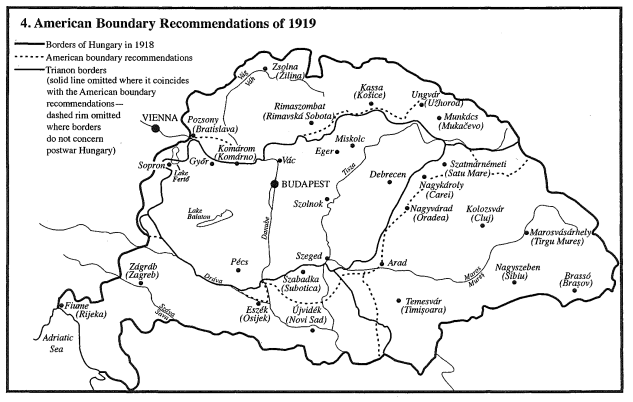

Though the protagonists of the Paris Conference agreed upon accepting President Wilson’s ideas, in fact they were hardly applied in practice. The standpoint of Woodrow Wilson was not that harsh as that of the Prime Minister of France. As President Wilson later stated, “considering that the Treaty of Trianon to which Hungary is a party was signed on June 4, 1920, and came into force according to the terms of its Article 364, but has not been ratified by the United States” (“Treaty Establishing Friendly Relations Between the United States and Hungary” 13. As the map below shows (Figure 1), President Wilson wanted to give what the delegation of Hungary wished to gain: those territories with Hungarian ethnic majority would have remained Hungarian territories. The American President did not want to punish Hungary as much as France, and that is why Wilson left the negotiations before signing the Trianon Peace Treaty, leaving only two countries to make the decisions: Great Britain and France. President Wilson’s intentions were directly in opposition to these. According to the Wilsonian fourteen points, the US President wished to open a new era in Europe’s history, which would have promoted the liberalisation of the world. Unfortunately, President Wilson stayed away from the peacemaking because the US Senate was too divided to accept the conditions of the settlement. However, the treaties with Germany, Austria and Hungary were finally signed on the 29th of August 1921 by U. Grant-Smith, Commissioner of the United States to Hungary, and Count Miklós Bánffy, Minister for Foreign Affairs to the Bethlen Government (Zeidler 2003, 311–312).

Figure 1: American Recommendations for the new Hungarian borders

Source: Romsics 2002, 181.

These points might be called guidelines rather than frames they should have worked between. As Harold Nicolson, who was an English diplomat serving as a junior clerk at the conference, remarked, “[g]iven the atmosphere of the time, given the passions aroused in all democracies by four years of war, it would have been impossible even for supermen to devise a peace of moderation and righteousness” (4). He was probably right on righteousness considering the emergence of World War II and the dissatisfaction of East-Central European nationalities up to the present. The British Prime Minister, David Lloyd George, maintained a liberal attitude emphasizing righteousness. He came to the conference with the desire to make a long-lasting and just peace. However, David Lloyd George was not able to decide on the fate of the Hungarian territories and people until the end of the conference partly because the leaders of the other two decision-making countries, the United States and France, could not stand on the same side.

The aim of the French Prime Minister, George Clemenceau, was clearer than Lloyd George’s: “Of the major Allies, the French were perhaps the best organised in planning ahead, mainly because they knew precisely what mattered to them and because their interests were not really global” (Marks 2). Gusztáv D. Kecskés claims that the change of official French foreign policy in favour of dismembering the Monarch was rather due to the changing military situation, and less because of the active campaign of the French experts, emigrant politicians or the pressure of the public opinion (131, 135–136). Notwithstanding this, it is still worth noting that these experts and pressure groups had a considerable impact on the French delegation. Between Clemenceau and Wilson the British PM stood in the middle of the events: Lloyd George did not want to allow the Hungarian government to sign a simple peace treaty, but did not have as great plans as the French delegation had. He was one of those politicians who in the beginning believed that Hungary needed to be punished for their war crimes, but eventually, he reconsidered the Hungarian case and tried to make a more appealing peace for Hungary. It is also an essential factor that Lloyd George often did not even listen to his advisors, mostly relied on the people who accompanied him to the peace talks (Bennett 156). Moreover, he occasionally did not even wish to listen to anyone: he wanted to create his own peace treaties (MacMillan 72).

David Lloyd George, who was against Hungary during most of the time turned to Wilson’s side, because he believed that if Croatia can be friendly towards Hungary apart from all the oppression they received as a part of the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy, then the Allied powers also need to listen to the Hungarian delegation (MacMillan 325). As it has been mentioned above, when the Romanian army marched as far as Budapest, it was the turning point because the delegations of Britain and France realized how unstable the political and military situation in Hungary was, and how the interference of the other countries proved to be harmful towards the Hungarian Peace Treaty. Lloyd George turned against Romania: according to him, it was only a chance for them to steal land using the opportunity that neither the Hungarian government, nor the Entente powers were able to predict how detrimental the outcome of the Peace Conference could be (MacMillan 328). The Romanians eventually occupied even Budapest, and with that they completely violated the agreement with the Entente. Eventually, Lloyd George and Clemenceau warned Romania and the countries which helped them, including Yugoslavia, to withdraw from Hungary, but still, it took quite a long time for the Romanian army to comply with this in March 1920. As Jan Smuts pointed out, “[w]hen the Hungarians and Romanians some time ago made a forward movement, the Peace Conference laid down a line of demarcation which neither should cross. It was a military, not a political line […]” (“General Smuts’s Mission to Hungary 1919”). This was among the first conflicts that the decision-making countries had to solve in connection with the possible outcome of the conference.

The British Prime Minister was among those politicians who decided the fate of the enemies of Britain and France. As the Prime Minister’s contemporary, Jane A. Stewart, wrote, “David Lloyd George, the son of a Welsh schoolmaster’s son, was among the conspicuous figures at the Peace Conference in Paris, directing the work of winding up the triumphant closing of the great war” (628). Lloyd George’s opening speech for the Peace Conference shows that he was aware of the fact that these peace negotiations would not be easy, and it would be among the greatest challenges that he, as a politician had to make:

"I believe that in the debates of this Conference there will at first inevitably be delays, but I guarantee from my knowledge of M. Clemenceau that there will be no time wasted. That is indispensable. The world is thirsting for peace. Millions of men are waiting to return to their normal life, and they will not forgive us too long delays." (“David Lloyd George’s Opening Address at the Paris Peace Conference, 18 January 1919”)

Even prior to the conference, one of the first steps that the Allied countries made after the First World War was to warn the Central Powers to withdraw all military forces from the invaded territories. The reparations had to be laid down, as well as the demilitarization of the Central Powers, mainly Austria-Hungary and Germany. The British Prime Minister and Clemenceau first decided not to admit Germany or any of its allies to the negotiations, which was unprecedented in European diplomacy. Traditionally, the defeated countries could speak for themselves, for their rights during the peace talks, but this time it was denied. In the case of the German peace treaty, the leaders of the peace negotiations did not allow any German leaders to participate at the conference, but for Hungary, they made an exception, mainly because it became clear that the Trianon Peace Treaty would cause great dispute even between France and Great Britain. While the Entente powers wanted to arrive at a decision about the fate of Hungary, they were also reluctant to listen to the Hungarian politicians and people. Despite this decision, the Hungarian delegation was eventually able to speak in front of the delegates of the Allied countries: this step also shed light on the difficulty of the process to get to the Hungarian peace treaty.

The whole process of the conference was characterized by disorganization. No programme was given along which the peace talks should have proceeded. The sections of the British Delegation suffered from lack of coordination and accurate instructions in their work. Their inevitable improvisation resulted in not being able to come to terms with the parties involved. Instead of it, they had to spend precious time on the aggressive and definite claims of the smaller powers including the Greeks, Romanians, Czechs, Slovaks and Serbs. Moreover, German, Hungarian and Turkish delegates were not even invited. The ad hoc appointed territorial committees did not know that their recommendations would be final, though they had the opportunity to consult experts, including Seton Watson, but economists’ considerations, like John Maynard Keynes,11 were not taken into account. As Harold Nicolson pointed out, this uncoordinated redrafting of territory has disastrous consequences of territorial and population loss to Hungary:

"The main task of the Committees was not […] to recommend a general territorial settlement, but to pronounce on the particular claims of certain States. This empirical and wholly adventitious method of appointment produced unfortunate results. The Committee on Rumanian Claims, for instance, thought only in terms of Transylvania, the Committee on Czech claims concentrated upon the southern frontier of Slovakia. It was only too late that it was realized that these two entirely separate Committees had between them imposed upon Hungary a loss of territory and population which, when combined, was very serious indeed. Had the work been concentrated in the hands of a ’Hungarian’ Committee, not only would a wider area of frontier been open for the give and take of discussion, but it would have been seen that the total cessions imposed placed more Magyars under alien rule than was consonant with the doctrine of Self-Determination." (104)

During the peace negotiations, it was clear that the British delegation did not represent the same point of view. The members of the delegation were divided into two groups: representatives of the cabinet and the Foreign Office. Depending upon which group a representative belonged to, their opinion could differ, or even be the opposite. Since the Foreign Office was characterized by an anti-Hungarian bias favouring a dismembered Monarchy, the members of the cabinet favoured a reorganized Monarchy, and supported the idea of ‘holding the Magyars together’ when questions about the new frontiers occurred.

After Charles IV’s disappointing agreement with Germany, different suggestions on the new frontiers of the successor states were presented. From the British Foreign Office, Lewis Namier, who was in close contact with Masaryk and Beneš, expressed his opinion on Amery’s proposal for a Danubian confederacy. Namier preferred the concept of forming nation states. He argued that creating a confederation is against the Danubian nationalities’ plan and that there was no reason to be concerned about the dysfunction of these nation states, but if tension occurred, the League of Nations would solve it. Namier envisaged a Romania together with the whole of Transylvania, and he took it for granted that Upper Hungary would be part of Slovakia (Romsics 2005, 57–58).

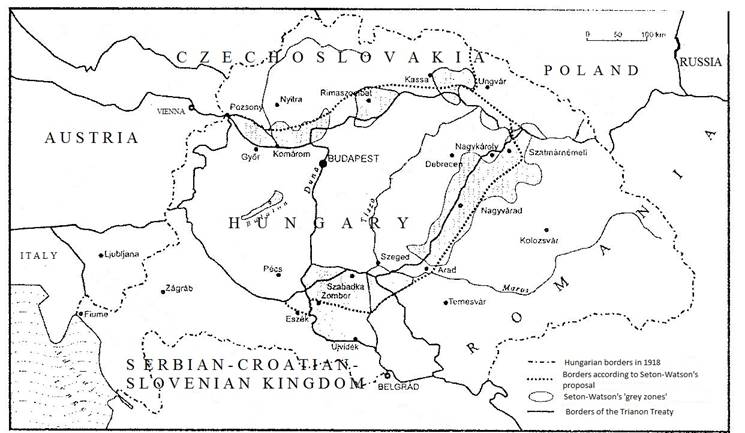

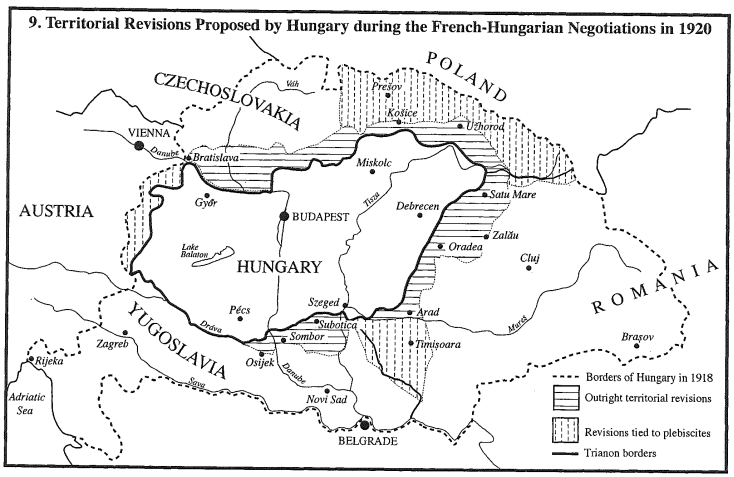

Among the above mentioned suggestions, Seton-Watson’s proposal was also discussed (Romsics 2005, 57–58). By Harold Nicolson’s own account, he and Allen Leeper “never moved a yard without previous consultation with experts of the authority of Dr. Seton Watson” (103). His proposal consisted of the concept of forming nation states as well. He created his plan keeping the Czechoslovak, Romanian and Yugoslavian strategic and economic interests in view against the Hungarian ones. Nevertheless, this plan was more favourable for Hungary than that which was accepted by the Peace Conference finally. He separated some so-called ‘grey zones’, which were inhabited mainly by Hungarians. Their affiliation should have been decided on the basis of careful international examinations (Figure 2) (Romsics 2005, 58).

Figure 2: The ’grey zones’ according to R. Seton-Watson’s proposal

Source: Romsics 2005, 59.

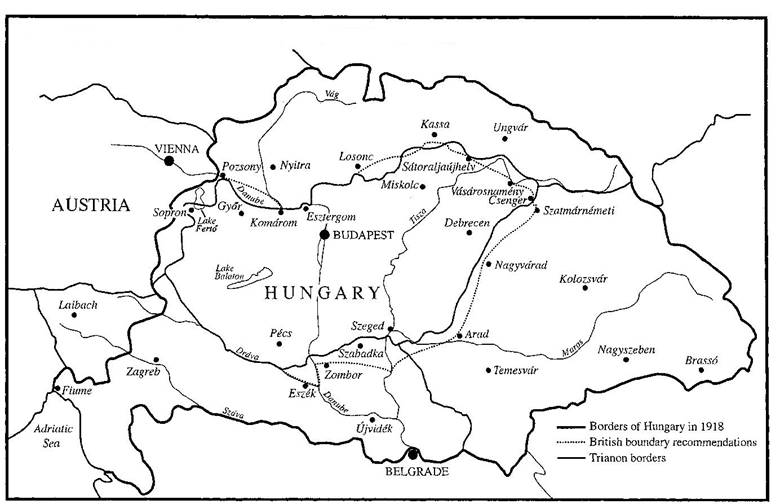

The British peace-delegation’s official suggestion for the Hungarian borders (Figure 3) was basically the same as that of Seton-Watson, except for the ‘grey zones’. Compared with Seton-Watson’s proposal, Csallóköz remained in Hungary, but in most cases, the British delegation decided in favour of the Slavs and Romanians, explaining their decision with economic reasons. This proposal was signed by the Assistant Under-Secretary of State, Eyre Crowe, the pro-Romanian Allen Leeper and the anti-Hungarian Harold Nicolson (Romsics 2005, 61–63).

Figure 3: British Boundary Recommendations

Source: Romsics 2002, 178.

These planned border-lines became more unfavourable for Hungary, when accepting Beneš’ demand, the British experts placed Csallóköz under Czechoslovakian control. In addition, the railway line of Szatmárnémeti-Nagykároly-Nagyvárad was given to Romania, and the Yugoslav-Hungarian borderline came to be traced along the Horgos-Kelebia-Kiskőszeg line so that Belgrade would be better protected (Romsics 2005, 64).

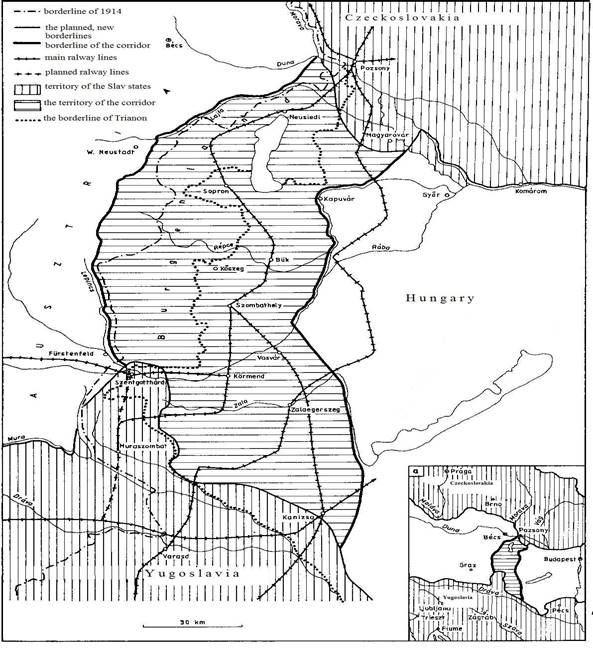

In a 1915 memorandum to the British Foreign Office, Tomáš Masaryk brought up the idea of a corridor which would link Czechoslovakia with Yugoslavia. This 11,500 km2 large area, would have included the Hungarian counties of Pozsony, Sopron, Moson, and Vas. The northern part of this corridor would have been devoted to Czechoslovakia, and the southern part to Yugoslavia. Masaryk’s explanation for forming this territory was the union of the Slavs and hindering the reunion of Austria with Hungary. In this way the Czech state would have had a passage to the Adriatic Sea (Figure 4).

Figure 4: Masaryk’s demand for the formation of a ‘Slav Corridor’

Source: Pándi 373.

However, Seton-Watson was against the idea of the corridor: “The claims to territory inhabited by Germans and to a corridor through western Hungary, though defensible on economic or strategic grounds, were clearly incompatible with the principle of national self-determination of which Masaryk was in general a most eloquent spokesman” (Seton-Watson 1981, 125). The Great Powers rejected the idea on 8 March of 1919, but one third of the territory of the corridor became Austrian land as Burgenland in August of 1919 though (Pándi 372). This also showed the impact political activists, like Seton-Watson, could exercise on the course of the peace conference.

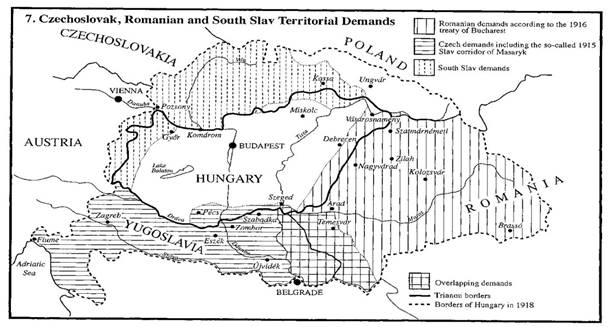

Lacking a separate committee which would have dealt with only the Hungarian borderlines, two other committees, that is, the Czecho-Slovak Territorial Committee and the Romanian-Yugoslav Committee, decided on Hungarian questions. Among the experts working here one could find Harold Nicolson as well. After hearing and studying the invited parties’ proposals, these committees made their own suggestions. These suggestions were generally accepted by the ‘Big Four’ or the Council of Foreign Ministers. The Romanian demands were submitted by Prime Minister Ion Brătianu. Ignác Romsics points out that the South Slav, Romanian and Czechoslovak demands were marked by a lack of restraint; their justifications were inconsistent and hypocritical. Brătianu laid his claim in accordance with the 1916 Bucharest Treaty. Romanian frontier suggestions extended southwest from Vásárosnamény towards Debrecen, then all the way down to the meeting of the Danube and the Tisza River (Romsics 2005, 144). He confirmed his demands with false statistics which showed exaggerated figures as for the Romanian population and underestimated data as for the Hungarian one (Figure 5).

Figure 5: Czechoslovak, Romanian and South Slav Territorial Demands

Source: Romsics 2002, 184.

The Czechoslovakian claims were presented by Prime Minister Karel Kramář and Foreign Minister Edvard Beneš on 5th of February, 1919. Besides forming the ‘Slavic Corridor’, connecting Czechoslovakia with Yugoslavia, and the area of Csallóköz, Beneš also laid a claim on the territories lying north from the Pozsony-Vác-Miskolc-Ung line. In this respect David Lloyd George remarked that Dr. Benes claimed territory inhabited by a preponderant majority of Magyars and the only reason for that was that it was essential to the Slovak population that they should have access to the Danube (913). Furthermore, Beneš announced that Czechoslovakia wished to constitute a federation with the Ruthenians (Romsics 2005, 74–75). The Czech Foreign Secretary argued that before the Hungarian conquest, Pannonia used to be under Slovak domination. According to him, the Hungarians persecuted the Slovaks up to the mountains and suppressed them. His other reason for gaining Northern Hungarian territories was economic. Czechoslovakia needed an exit to the sea, which would assure a direct usage of the Danube, thus the Danube River as a borderline was essential. Additionally, they needed this territory by reason of the railway connections which could be found there, though, Beneš admitted that this area was mainly inhabited by Hungarians. Nevertheless, he reasoned with unreliable Hungarian statistics and the racially mixed population of the area (Zeidler 2003, 50–51).

The Yugoslav claims were divided into three sections in Southern Hungary (Figure 5). They argued that they needed these areas due to strategic reasons. The first section ran along the Maros River from Arad to the Tisza River. This line was considered a strategically appropriate line of defence. The second section was located between the Tisza and the Danube Rivers. This area would have allowed the Yugoslavs to defend the whole of Bácska in case of an attack from the north. The third section ran from the Danube up to the Italian borderline following the Dráva River. This line was also considered a well defensible section against an assumable attack (Zeidler 2003, 61).

The more severe these frontiers became, the more Hungarian people were ordered under foreign rule. When it became obvious, Lloyd George expressed his objection to it. He predicted that there would never be peace in Europe if significant amount of Hungarian inhabitants came under other states’ rule. He suggested a humanistic approach when drawing borderlines, that is, every nation should be given its own motherland, which approach should precede every other strategic, economic or transport approaches (Romsics 2005, 64–65). Lloyd George ordered Field Marshall Jan Smuts to make an attempt to alter the British delegation’s border-suggestions. According to an article referring to the fact that David Lloyd George wanted to keep an eye on Hungary even before the peace negotiations, “General Smuts is […] being sent to Budapest to inquire into the position and supply the Conference with first-hand information on the whole question” (“General Smuts’s Mission to Hungary 1919”).

General Jan Christian Smuts became member of the War Cabinet in 1917. The fact that he was a foreigner (born in the Commonwealth in Southern Africa) made him a good negotiator, he was fighting against the British in the Second Boer War, and so he represented a different point of view that could be useful in the rapidly and radically changing political and military situation. David Lloyd George, Lord Milner (another member of the War Cabinet) and Smuts were considering Austria-Hungary’s separate peace attempts, but Smuts did not really sympathise with either the Austrians, or the Hungarians. However, the circle of David Lloyd George had an opportunist point of view; they accepted everything that would have stopped the war. After the Paris Peace Conference received the letter from Béla Kun, the Foreign Secretary of the Hungarian Soviet Republic in which he stated he would gladly receive an Entente diplomatic mission, the British Prime Minister was thinking about sending Smuts as the leader of this mission. In spite of the resistance of the Foreign Office and the French, the Peace Conference accepted the propositions of Lloyd George. Nevertheless, the Foreign Office managed to send their two representatives Harold Nicolson and Allen Leeper, members of the Czechoslovak and Yugoslavian-Romanian Territorial Council (Lojkó 327–329). At the negotiation on 5 April 1919, Kun committed an error, he demanded too much, and Smut interpreted it as the refusal of the British propositions, so the mission had ended. Notwithstanding this fiasco, at the end of his visit, Smuts bent towards the offer that Kun proposed: summon the people of the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy and decided the fate of the borders with them, not with the exclusion of them (MacMillan 326). Moreover, Smut did not evaluate his mission as unsuccessful, as on his way back to Paris, he stopped in Prague and Vienna, and the Czech President Masaryk agreed on the necessity of summoning a Central European Economic Conference (Romsics 2002, 95–96). He wrote in his final report that a second Smuts mission was planned, but it was cancelled due to the unlucky circumstances (reaching a critical point in the drafting of the German peace, illness of President Woodrow Wilson) (Lojkó 330–332).

The member of the Smuts mission, Nicholson gave voice to his unfavourable view on Hungarians in his memoires:

"[…] “Austria”, “Hungary”, “Bulgaria”, or “Turkey” were not in the forefront of our minds. It was the thought of new Serbia, the new Greece, the new Bohemia, the new Poland which made our hearts sing hymns at heaven’s gate. This angle of emotional approach is very significant. I believe it was a very general angle. It is one which will not be apparent from the documents in the case. It is one which presupposes a long and fervent study of “The New Europe”- a magazine then issued under the auspices of Dr. Ronald Burrows and Dr. Seton-Watson with the doctrines of which I was overwhelmingly imbued. Bias there was, and prejudice. But they proceeded, not from any revengeful desire to subjugate and penalise our late enemies, but from a fervent aspiration to create and fortify the new nations whom we regarded, with maternal instinct, as the justification of our sufferings and our victory. The Paris Peace Conference will never properly be understood unless this emotional impulse is emphasized at every stage[…] My feelings towards Hungary were less detached. I confess that I regarded, and still regard, that Turanian tribe with acute distaste. Like their cousins the Turks, they had destroyed much and created nothing. Buda Pest was a false city devoid of any autochthonous reality. For centuries the Magyars had oppressed their subject nationalities. The hour of liberation and of retribution was at hand." (26–27)

He acknowledged that he himself and his colleagues were under the influence of The New Europe. He mentioned the name of Seton-Watson explicitly, which clearly showed his authority and influence on the British delegation. From this perspective, the Hungarians were ‘demonised’, and, in contrast, the countries and national aspirations The New Europe supported were excessively glorified, thus they made this political and rational decision as something heavenly and transcendental. He claimed that these emotions and decisions could only be understood in the context of the Paris Peace Conference. Furthermore, Nicolson claimed that Hungarians and their cousins, the Turks could not do anything but simply destroy everything that was not true. In such a religious zeal, it is obvious that these ‘experts’ could not make rational verdicts, and they committed huge mistakes. He even admitted his bias, but did not evaluate it as something negative.

The diplomatic mission of Sir George Russel Clerk is also important to be mention, as during the war, Clerk sympathised with the circle of The New Europe (Lojkó 333). After a prolonged negotiation with the Romanians in September 1919 to stop the Romanian military advancement in Hungarian territories, Clerk stopped at Budapest (Romsics 2002, 114). During his short visit, he met people with various political affiliations, such as Ernő Garami, social democrat leader, who made him conclude the Hungarian problems could only be solved if a stable and viable government would have come into existence, which was acknowledged by the Peace Conference instead of sending ultimatums (Lojkó 334). Clerk did not think that the Friedrich government relying on the gentries could fulfil this role, as they did not have large social support, and the Romanian were still advancing, thus making Hungary vulnerable to another Bolshevik or extreme right dictatorship (Romsics 2002, 114–115). He redacted these principles in his memoranda written on 7 October.

The effect of this memorandum was that the Supreme Council of the Paris Peace Conference sent him on another mission to Budapest as their High Representative. His major tasks were to enforce the Romanian retreat and to create a Hungarian government based on mutual agreement. On 23 October, he arrived in Budapest, and commenced the negotiations on the next day. His negative attitude towards the Hungarian had gradually changed. He trusted Miklós Horthy despite the fact that the French observers regarded Horthy’s soldiers as adventurer who should have been disarmed. In addition, it must be remarked that the French were not worried about Hungarian democracy, but they feared the revenge of Szeged. Clerk’s positive opinion even convinced Eyre Crowe. With the help of Clerk, the Huszár government had been formed. On 1 December 1919, the Hungarian delegation had been invited by George Clemenceau in the name of the Supreme Council that signalled the end of the Hungarian crisis, and the end of exceptional Anglo-Hungarian relationship (Lojkó 334–337). Smuts, one of the leaders of this committee, at the end of his visit bent towards the offer that Kun proposed: summon the people of the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy and decided the fate of the borders with them, not with the exclusion of them (MacMillan 326).

Originally, both the diplomatic missions of Jan Smuts and Sir George Russel Clerk aimed at stabilising the Carpathian Basin after the Great War. The pro-Hungarian political groups within the British delegation also supported these missions, nonetheless, Seton-Watson and Steed also had an impact on these missions as Harold Nicolson and Allen Leeper were members of the Smuts mission and maintained direct contact with the British Slavophil groups. Contrary to his earlier neutral position, Nicolson became unfairly critical towards Hungarians due to his false pretensions and excessive emotionality (26–27).

As a result of his negotiation with Masaryk, Csallóköz with 400-500 thousand Magyars would have remained inside Hungary (Romsics 2005, 74). This proposal, however, never got accepted on a higher level of discussion though, and on 12 May 1919, the Council of Ten12 accepted the original British plan without any modification. In the disputes over borderlines to follow, Lloyd George stood up for Hungary for several times. On 10 June, he held the Czechs responsible for the Czech-Hungarian military conflict, who wanted to seize the northern Hungarian coal-fields and industry built upon it. Furthermore, on 12 June, he suggested that the Council of Four should hear the Hungarian delegates as well, before the new borderlines would be revealed (Romsics 2005, 68).

At the end of 1919 and the beginning of 1920, several British people of high rank disapproved the decisions made by the Peace Conference. The most significant opponent was James Bryce,13 who criticized the Romanians for their armed aggression in Transylvania, and the Peace Conference for their not hearing the Hungarian delegates at all. He reckoned Romania’s obtaining of the whole of Transylvania together with the Partium and Bánát outrageous, because this territory was inhabited by a significant proportion of Hungarian population (Romsics 2005, 69). While advocates of the Hungarian affairs envisaged a future war due to unfair ethnic arrangements, the anti-Hungarian group referred to the guaranteed minority rights and hoped for a prosperous economic cooperation between the newly outlined states, including Hungary, but failed to take hostility between them into account.

During the consultations in spring 1920, the disagreement between the British Foreign Office and Lloyd George on Hungarian matters was evident for everybody. Against their own Prime Minister, the British Foreign Office advocated the French proposals with regard to the Hungarian frontiers. Except Nitti, nobody stood by Lloyd George, so the reconsideration of these frontier lines was not possible. Although on 5 May 1921, the Treaty of Trianon became ratified by the British Parliament as well, several members of the ruling elite14 considered it deeply unjust and incompatible with the Wilsonian principles (Romsics 2005, 76–77).

The Romanian conflict helped the Hungarians in one matter: though Hungary was originally not entitled to express any opinion in this process, the guest Hungarian delegation obtained an opportunity to share their views after they received the draft of would-be conditions of the proposed peace. The delegation, led by Count Albert Apponyi, set off on the 5th of January, 1920. Whether it was the right decision to select Apponyi as the leader of the delegation or not was not congruent. On the one hand, the Count was among those politicians who were still respected by the people, but on the other hand, he was one of those politicians who were pro-German, which could have lessened the country’s chance for a fair peace treaty (Zeidler 2009, 26–27). The Entente countries and their alliescould use the Paris Peace Conference for two things: to punish and to reward (Zeidler 2009, 28). It meant that those who helped defeat Germany and its allies would be rewarded, which sometimes became equal to why Hungary had to lose the territories with Hungarians living on it. Knowing that the Allied powers already decided what to do with the country, Hungarians at home had already set out to devise a study, edited by Count Pál Teleki, which detailed the demographic boundaries of Hungary. The aim of Teleki was to prove the plausibility of ethnic borders, so that no Hungarian people could become the subject of another country, such as Romania (Cartledge 105–107). Count Albert Apponyi’s splendid speech had some influence, since both the British Foreign Secretary, Lord Curzon, and the Prime Minister, Lloyd George, urged new negotiations according to the Hungarian Notes. Hungary was given the opportunity to react to the prepared treaty. In these notes Hungary protested against the dismembering, the reparations clauses and especially the economic reasons which were emphasized more than the ethnic ones. Hungary demanded plebiscites in areas with mixed nationalities and were intended to be annexed by the neighbours. (Dockrill and Goold 126). Because Georges Clemenceau, the French Prime Minister still thought of Hungary as a non-reliable country, and he stated that he did not want to hear about the modifications, so Apponyi had to approach the problem of detaching territories from Hungary from another angle: the question of a referendum (Cartledge 112). During his speech, the Count highlighted that losing 2/3 of the territory and millions of Hungarian people would be unprecedented in the history of all peace treaties (Romsics 2000, 128). Apponyi pointed out that the peace treaty Hungary had to receive was crueller than what any other defeated state had to accept. According to Lloyd George, Apponyi’s speech was really convincing, it spoke to the heart of the audience, and it was not full of simple data. The British Prime Minister even asked for the map that Apponyi attached to support his speech (Figure 6), which contained how the borders should be drawn in relation to the Hungarian-inhabited territories. Apponyi’s other claim was to call referenda, because it was a possibility according to the American President’s peace terms (Cartledge 112).

All of this was advocated by the Italian Prime Minister, Francesco Nitti as well, but the French representatives, Alexandre Millerand, who replaced G. Clemenceau in his office, and Ambassador Philippe Berthelot, ardently rejected any alterations. In January 1920, a new cabinet was appointed in France. The concept of the new government differed from that of the old one. Millerand and Berthelot favoured the idea of the Monarchy’s reorganization instead of its dissolution. Nevertheless, the French security policy remained the same, and the Treaty of Trianon was considered as part of the reorganization of the East-Central European region in order to weaken Germany (Romsics 2005, 30–32). Finally, the document to be signed was placed in front of the Hungarians without any alterations, since, according to the British representative, Sir Eyre Crowe’s opinion:

"When we come to face these ethnographical difficulties it makes a great difference whether they arise between the Roumanians and the Hungarians who are our enemies, or between the Roumanians and the Serbs, who are our Allies. In the first case if it were found to be impossible to do justice to both sides, the balance must naturally be inclined towards our ally Roumania rather than towards our enemy Hungary." (Lloyd George 920)

Consequently, Hungary had to suffer these territorial losses not because of her punishment in the first place but because of appeasing the claims of the Romanians and the Slavs. Since France was the leading force at this peace conference, it was essential for Clemenceau to adjudge as much as possible to France’s above mentioned allies. Clemenceau accepted the nationalities’ plans about hindering Bolshevism, or weakening Germany.

Figure 6: Hungarian recommendation for the new borders

Source: Romsics 2002, 186.

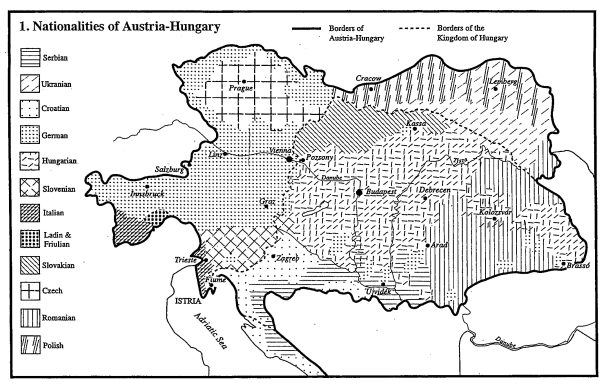

Hungary tried its best to avoid what could not be avoided, but eventually, Clemenceau’s idea prevailed and Hungary lost more than two-third of its territory. The delegates of the Simonyi-Semadam government (Ágoston Bernát and Alfréd Drasche-Lázár) signed the Trianon Peace Treaty on the 4th of June, 1920 (Szidiropulosz 191). The country became the greatest casualty of World War I, as the Trianon Treaty was much crueller than what Germany had to sign, mainly because of the demands of the countries that helped the Allied countries during the war. As Edvard Fueter stated, “Hungary formerly was composed of many different language units, among which the Magyars formed only the largest of the minorities. Now it has become entirely Magyar, excepting for the German components in the Western districts” (157–158). It is an important statement, because the leader of Great Britain was the one who was willing to listen to the Hungarian delegation’s reasons in order to avoid the dismemberment of whole country. As the map below shows (Figure 7), many nationalities lived within the borders of historic Hungary, but many people who were Hungarians had to live outside the borders after the Trianon Treaty which seemed to be disregarded by the conference. The day the Trianon Peace Treaty was signed, everything stopped in Hungary: the people and the machines as well, because they realized that this was the moment that would always have an effect on their lives (Szidiropulosz 191).

Even during the Paris Peace Conference, it became obvious for the British Prime Minister, David Lloyd George that after Britain and France, forced this treaty on Hungary, there could not be real and long lasting peace in Europe. Lloyd George admitted that when they became aware of the fact that Hungary lost two-third of its previous territory, it was already too late: they could not change the content of the peace treaty. The outcome of the Trianon Treaty could not be predicted because this was the very first treaty that prescribed such tremendous changes and stipulations in the life of a whole nation. This is why Lord Rothermere decided to bring the spotlight to the Hungarian situation. According to him, there were not many British people who were aware of what happened during the Peace Conference, or after, not to mention the understanding of the Hungarian situation in 1920. His decision to stand up for the rightfulness of Hungarian revisionism created a considerable basis for the acts in Hungary. “However, three million Magyars were left outside the contracted frontiers, a fact which Hungary neither forgave nor forgot as it blamed the peace treaty for all social and economic problems” (Marks 21). According to Lord Rothermere, the treaty could be best understood for the British people if they had imagined that the British people would have been divided among Germany, Russia and Turkey, because they were promised British land after the war (13). Because in the end, that was exactly what happened to Hungary: its territory was divided, and given to other countries with Hungarians living on those territories which made the Trianon Peace Treaty one of the cruellest decision in the history of peace treaties.

Figure 7: Nationalities of the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy

Source: Romsics 2002, 182.

Conclusion

The paper has examined those political reasons which affected the British politicians and activists in shaping their views on the Hungarian post-war settlement and the creation of the Trianon Peace Treaty. Maintaining the power balance in Europe was the main political interest of Great Britain. In order to reach this aim, the politicians’ main motivations at the peace settlement after the war were hindering German expansion towards the Balkans and Russian Bolshevism towards Europe, securing a long-lasting peace on the continent simultaneously.

Participants at the Peace Conference were not on the same opinion regarding the way that could have led to an enduring peace. Even within the British delegation, representatives of the Foreign Office opposed to that of the Cabinet. While the British Foreign Secretary advocated the Czech, Romanian, and Yugoslav claims, which meant reducing the territory of historical Hungary to its one-third, the British Prime Minister, David Lloyd George, agreed with Woodrow Wilson’s conception about self-determination. On several occasions, Lloyd George emphasized that the notion of self-determination should have been applied to the loser nations as well. Besides, he urged an invitation of the representatives of the Hungarian government to the peace conference, but by the time Count Apponyi arrived in Paris, the new borders for Hungary had already been settled.

Unlike Lloyd George, Grey’s attitude could be considered anti-German while he was in office until the end of 1916. He advocated all the proposals of the later formed alliance of the Little Entente, because he saw Hungary’s weakening as one of the guaranties of preventing German expansion. His intention coincided with Robert Seton-Watson and Wickham Steed’s views, who agitated for the Slav nationalities’ ambition of independence and the dismemberment of Austria-Hungary. The objective of their articles in The Times, The Spectator and later The New Europe was to convince British people of the legitimacy of those ambitions. They also made reports and suggestions on Hungarian cases for the Foreign Office, according to which the officials could form their own standpoint.

Although Lloyd George’s liberal attitude was favourable for Hungary, he did not receive enough advocacy and support during the discussions about the new Czechoslovak, Romanian and Yugoslav borders. President Wilson did not take part in the final negotiations, thus, he could not support Lloyd George in his opposition to the new borders. The Italian Prime Minister, Francesco Nitti’s help did not prove to be sufficient either against the ardent representatives of the anti-German views, consequently, Hungary had to suffer the most severe conditions accepted by the conference.

Works Cited

- Arday. L. 2009. Térkép, csata után: Magyarország a brit külpolitikában 1918-1919 [Map drawn after Battle: Hungary in British Foreign Policy 1918-1919], Budapest: General Press.

- Bánffyné Kalavszky Gy. – Nagy E. – Prantner Z. – Toroczkay B. 2013. Trianon 1920 – A történelem tanúi [Trianon 1920 – The Witnesses of History], Kisújszállás: Szalay-Pannon-Literatúra Kft.

- Bennett, G. H. 2003. “British Foreign Policy, 1900-1939.” A Companion to Early Twentieth Century Britain, edited by Chris Wrigley, Oxford: Blackwell, 125–137.

- Beretzky, Á. 2005. Scotus Viator és McCartney Elemér: Magyarországkép változó előjelekkel (1905-1945) [Scotus Viator and McCartney Elemér: The Image of Hungary with Varying Precursors (1905-1945)], Budapest: Akadémiai Kiadó.

- Bryce, Viscount. 1923. Memories of Travel, London: Macmillan.

- Cartledge, Bryan. 2009. Trianon egy angol szemével, Budapest: Officina Kiadó.

- Chopin, J. “Bibliographie.” La Nation Tchèque, Vol. 2, No. 8, Aug 15, 1916, p. 126. URL: https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k6558845m/f14.item (Access: 12.11.2021)

- Cora, Zoltán. 2019. “Alternatívák és valóság: Magyarország a brit és francia politikában az első világháború előtt és alatt [Alternatives and Reality: Hungary in British and French Policy Before and During the First World War].” A végnapok képei. Az I. világháború befejezésének 101. évfordulóján tartott tudományos szimpózium előadásai, edited by Czagány Gábor – Horváth Gábor, Szeged: Gerhardus Kiadó, 7–32.

- David Lloyd George’s Opening Address at the Paris Peace Conference, 18 January 1919. Source Records of the Great War 7. URL: https://www.firstworldwar.com/source/parispeaceconf_lloydgeorge.htm (Access: 17.03.2021).

- Denis, E. “Les Slovaques.” La Nation Tchèque, Vol. 2, No. 15, December 1, 1916, pp. 230–237. URL: https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k65584153/f6.item (Access: 18.03.2021).

- De Quirielle, “Un programme de M. H. Wickham Steed.” La Nation Tchèque (May 15, 1916) Vol. 2, No. 2, May 15, 1916, pp. 19–24. URL: https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k65584064/f3.item (Access: 18.03.2021)

- Dockrill, M. L. – Goold, D. 1981. Peace without Promise – Britain and the Peace Conferences 1919-23. London: Batsford.

- Dockrill, M. L. – Steiner, Z. 1980. “The Foreign Office at the Paris Peace Conference in 1919.” The International History Review, Vol. 2, No. 1, 1980, pp. 55–86.

- Finch, G. A. 1919. “The Peace Conference of Paris, 1919.” American Journal of International Law Vol. 13, No. 2, pp. 159–186. DOI: https://doi.org/10.2307/2188076

- Frank, T. 2018. “Három professzor. Az angol szak kezdetei Budapesten, 1886-1967 [Three Professors: The Beginnings of the English Major in Budapest, 1886-1967].” Britannia vonzásában, edited by idem, Budapest: Gondolat Kiadó, 99–113.

- Fueter, E. 1921. “The Regeneration of Hungary: A Survey of Post-War Conditions in the New Magyar State.” The Journal of International Relations Vol. 12, No. 2, 147–172.

- General Smuts’s Mission to Hungary. (Australian and N.Z. Cable Association) Paris, April 2. Colonist Vol. 61, No. 15039 (April 5, 1919), URL: https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/TC19190405.2.24.1.3?end_date=06-04-1919&items_per_page=50&query=general+smuts&snippet=true&start_date=04-04-1919&type=ARTICLE (Access: 17.03.2021).

- Gergely, J. – Pritz, P. 1998. A trianoni Magyarország 1918-1945 [Hungary after Trianon 1918-1945], Budapest: Vince Kiadó.

- Jeszenszky G. 1994. Az elveszett presztízs. [The Lost Prestige.] Budapest: Magyar Szemle Alapítvány.

- Kecskés, Gusztáv D. 2010. “A” trianoni békeszerződés kelet-közép-európai háttere a francia külpolitika perspektívájában.” Kisebbségkutatás Vol. 19, No. 2, 131–142.

- Lloyd George, D. 1938. The Truth about the Peace Treaties. Vol. I., London: V. Gollanz.

- Lojkó, M. 2004. “Brit békemiszziók Közep-Európában: Smuts tábornok és Sir George Clerk tárgyalásai 1919-ben.” Angliától Nagy-Britanniáig: magyar kutatók tanulmányai a brit történelemről, edited by Frank Tibor, Budapest: Gondolat, 327–339.

- MacMillan, M. 2005. Béketeremtők: az 1919-es párizsi békekonferencia [Peacemakers. The Paris Peace Conference and Its Attempt to End War], Budapest: Gabó.

- Magyarics, T. 2007. “Nagy-Britannia Közép-Európa-politikája 1918-tól napjanking [The Central European policy of Great Britain from 1918 to the Present Day].” Grotius, 3-49. Available: http://www.grotius.hu/doc/pub/RHIXRV/27%20magyarics%20tam%C3%A1s%20nagy-britannia%20k%C3%B6z%C3%A9p-eur%C3%B3pa-politik%C3%A1ja.pdf Access: 23.03.2021.

- Marks, S. 2003. The Illusion of Peace: International Relations in Europe, 1918-1933, New York: Palgrave.

- Nicolson, H. 1945. Peacemaking, 1919, London: Constable and Company Ltd.

- Ormos, M. 1983. Padovától Trianonig 1918-1920 [From Padova to Trianon 1918-1920], Budapest: Akadémiai Kiadó.

- Pándi. L. 1997. Köztes-Európa 1763-1993 [Middle-Europe 1763-1993], Budapest: Osiris.

- Papp, E. I. 2020. “British and French Political Approaches Towards Hungary at the Turn of the 20th Century.” Kiss Attila (ed.:) Distinguished Szeged Student Papers, Acta Iuvenum II, edited by Kiss Attila, Szeged: JATE Press, 89–138.

- Péter, L. 2012. Hungary’s Long Nineteenth Century. I., Boston–Leiden: Brill.

- Romsics, I. (2005): Helyünk és sorsunk a Duna-medencében [Our Place and Fate in the Danube Basin], Budapest.

- Romsics, I. 2000. Magyar Történeti Szöveggyűjtemény 1914-1999 [Sourcebook on Hungarian History, 1914-1999], Budapest: Osiris.

- Romsics, I. 2002. The Dismantling of Historic Hungary: The Peace Treaty of Trianon, 1920, New York: Columbia University Press.

- Rothermere, H. S. H. 1939. My Campaign for Hungary, London: Eyre and Spottiswoode.

- Scotus Viator. 1908. Racial Problems in Hungary, London: A. Constable and Co. Ltd.

- Seton-Watson, R. W. 1916. German, Slav, and Magyar: A Study in the Origins of the Great War, London: Williams and Norgate.

- Seton-Watson, H. and C. 1981. The Making of a New Europe, London: Methuen.

- Steiner, Z. S. 1969. The Foreign Office and Foreign Policy, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Stewart, Jane A. 1921. “A Great Man of The Day.” Journal of Education Vol. 94, No. 23, 628.

- Szidiropulosz, Archimédesz. 2003. Trianon utóélete [The Afterlife of Trianon]. Budapest: XX. Század Intézet.

- “Treaty Establishing Friendly Relations Between the United States and Hungary.” The American Journal of International Law Vol. 16, No. 1, Supplement: Official Documents (Jan 1922), 13–16.

- Yolland, A. B. 1906. Alexander Petőfi, Poet of the Hungarian War of Independence, Budapest: Franklin.

- Zeidler, Miklós. 2009. A revíziós gondolat [The revisionist idea]. Pozsony: Kalligram.

- Zeidler, Miklós. 2003. Trianon, Budapest: Osiris.

Notes

1 I am indebted to one of my former MA Thesis writers, Erik Papp, who wrote as well as published an excellent MA Thesis on the topic: British and French Political Approaches to Hungary at the Turn of the 19th–20th Century. Szeged, 2018. The published version of his thesis is Papp 2019. ↩

2 “To-say it is no longer possible or necessary to argue about the exact strength of Pan-Germanism on the eve of war. For in war moderate counsels are necessarily thrust into the background on every side; and to-day Germany is writing the Pan-German programme in letters of blood on the face of Europe. Her alliance with Austria-Hungary has become more indissoluble than ever, and the idea of a customs-union as a final seal upon the bond is being propagated by prominent politicians, publicists, professors, and bankers…To-day we are faced by a solid mid-European bloc of 120 millions, which can only be shattered or pared down by military effort, but cannot be split up by diplomacy…Unless we are prepared to desert our Allies and conclude an ignominious peace with Germany, we must counter the German plan of “Mitteleuropa” and “Berlin-Bagdad” by placing obstacles in its path. In one of its main aspects this war is the decisive struggle of Slav and German, and upon it depends the final settlement of the Balkan and Austrian problems […] Germany can only be defeated if we are prepared to back the Slavs and liberate the Slav democracies of Central Europe […] The essential preliminaries then, are the expulsion of the Turks from Europe and the disruption of the Habsburg Monarchy into its component parts. On its ruins new and vigorous national states will arise. The great historic memories of the past will be restored to the Commonwealth of Nations, and in their new form will constitute a chain of firm obstacles on the path of German aggression. (I) Poland, freed from its long bondage […] (2) Bohemia, who has been the vanguard of the struggle against Germanization for eight centuries […] (3) The small and landlocked Serbia of the past will be transformed into a strong and united Southern Slav State […] (4) independent Hungary, stripped of its oppressed nationalities and reduced to its true Magyar kernel […] emancipated from the corrupt oligarchy […]; and (5) Greater Roumania, consisting of the present kingdom, augmented by the Roumanian districts of Hungary, Bukovina, and Bessarabia.” Seton-Watson 1916, 171–174. ↩

3 For the antecedents of this in detail, see: Jeszenszky 1994. ↩

4 “Living far away from my native land, I have learned to love and admire Hungary, her people, her culture, her literature. The latter is the work of a great and noble race, which, despite the oppressions to which it has been subjected, despite the centuries of desperate struggle against the inroads of the devastating Turks, who might, for the generous self-sacrifice of the Magyars and their brilliant leaders, have overrun Europe, have produced a literature of which any civilised nation might well be proud.[…] I shall be able to render services far more valuable and lasting than could be done by scores of pamphlets or historical studies. Hungary and the Hungarians have, during the past, been but little known; the many distorted and ill-meaning reports spread about the country and its inhabitants cannot be better answered than by a study of literature. The many-headed dragon of malice and calumny cannot be more effectively combatted than by an insight into the character and thought of the people which has been so shamelessly maligned.” Yolland 3–4. ↩

5 “Nor do these pages, when I look over them, seem fully to convey a sense of the delicious freshness and wildness of the scenery, with its magnificent rock-peaks rising out of its sombre forests; still less perhaps of the charm which the simple, free and easy Hungarian life, the frank and hearty manners of the people, have for anyone who can find himself in sympathy with them. Nowhere in the European continent does an Englishman feel himself more at home. After a few weeks among the Magyars one can enter into the spirit of the national adage—an adage which a late respected missionary (a staid old Scotsman, sent to Pesth by the Society for the Conversion of the Jews) whose persistence in the duty he was charged with did not check his enjoyment of general society, is said to have been fond of repeating: "Extra Hungariam! non est vita, / Vel si quidem est, non est ita.” Bryce 139–140. ↩

6 The Spectator, November 2, 1907. URL: http://archive.spectator.co.uk/. (Access: 29.06.2020). ↩

7 Jules Chopin: Bibliographie. La Nation Tchèque, August 15, 1916. (1916) 126. URL: http://gallica.bnf.fr/accueil/?mode=desktop. (Access: 29.06.2020); Pierre de Quirielle: Un programme de M. H. Wickham Steed. La Nation Tchèque, May 15, 1916. (1916) 19-24. URL: http://gallica.bnf.fr/accueil/?mode=desktop. (Access: 29.06.2020); Ernest Denis: Les Slovaques. La Nation Tcheque, December 1, 1916. (1916) 230-237. URL: http://gallica.bnf.fr/accueil/?mode=desktop. (Access: 29.06.2020). ↩

8 English translation by Erik Papp, see Papp 2020. ↩

9 Fernand Vix was the appointed military leader in Hungary by the Entente powers, whose task was to supervise the Hungarian government, and its relationship with the Little Entente and Switzerland. It was also his assignment to make sure that Hungary kept to the conditions of the armistice. ↩

10 In the autumn of 1918, the British peace delegation sat down to appoint the frontiers of the new states. The most reasonable plan for Hungary was prepared by Leopold Amery, who was Hungarian on his mother’s side. ↩

11 The British economist suggested a new, world-wide trading system including Germany and Russia, too, to balance world-economy after the war. ↩

12 The Council of Ten, or the Supreme Council was constituted by the heads of government and foreign ministers of the USA, Great Britain, France, Italy and Japan to monopolize all the major decision making. ↩

13 British politician, Ambassador to the United States. He advocated the establishment of the League of Nations. ↩

14 Members of the House of Lords who refused it: Lord Newton, Viscount Bryce, Lord Sydenham, and Lord Montagu of Beaulieu. ↩

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.