Introduction

Wharton’s published travel pieces constitute what I propose to call ‘the Wharton map.’ Wharton’s published travel texts cover three European areas. First, she wrote about Italy and the presence of the Renaissance and Baroque past in Italian scenes in her Italian Villas and Their Gardens (1904) and its companion piece Italian Backgrounds (1905). Secondly, she concentrated on France, exploring historical continuity in French landscapes and architecture, especially cathedrals, in her A Motor–Flight through France (1908) and Fighting France (1915). Her French Ways and their Meaning (1919) is not a travel text but an ethnographically oriented account of French national traits as such. Thirdly, she wrote about her trip to Morocco, then a French protectorate, producing the first tourist book of the country in English titled In Morocco (1920). Wharton reported about “the strange survival of mediaeval life” (Wharton 1996, x) in the country before tourists and modernization erased it (Ibid.). This map is to be extended by her Aegean writing.

Academic research has produced further travel pieces to this set of five, expanding the Wharton map by previously unknown texts. In 1992, Wharton’s diary of her 1888 Aegean titled The Cruise of the Vanadis was published (Lesage 2004 (1992)). Frederick Wegener republished Wharton’s celebratory essay on French colonial administration in a piece linked to Wharton’s accounts of Morocco (Wharton 1998(1918)). In 2011 Patricia Fra López published Wharton’s 1925 diary of her trip to Compostela with Walter Berry and an unfinished essay titled “Back to Compostela” with a long introduction about Wharton’s visits to and notions of Spain. Also, a translated section of Wharton’s article in French titled “America at War” that eventually became part of her French Ways and Their Meaning was published in the TLS in 2018 (Ricard 2018). As the list shows, new items from the archive continue to shape and sharpen our knowledge of Wharton as an author and as a person (Ohler 2019, 28).

At the moment, the Osprey Notes exists as a notebook in a folder of the Beinecke Library at Yale. It contains fifteen handwritten pages of sites Wharton visited in 1926. There are ten entries altogether but only nine descriptive passages of visits on the Ionian Sea and in and around Athens, six pages of typescript altogether. The fragments capture visual impressions of a specific landscape or architectural sight and catalogue the presence or lack of beauty, peace, mystery experienced during the visit. The last entry titled “Moonlight on the Parthenon” remains only a caption, as it was never completed. A fragment itself, the Osprey Notes cannot function as a full-fledged travel book, nor does it develop a sustained argument about classical Greece or its retrieval in the present. However, the passages highlight certain sites and share a language of admiration that hint at the wider importance of the Greek impressions for Wharton the traveler. Also, in subsequent commentaries Wharton always speaks highly of the trip. So despite the scant amount of actual text and because of its later significance, it is worth reconstructing the actual context of the fragment and try to consider its entries in relation to Wharton’s earlier travel output and also frame its possible place in Wharton’s relation to traditions of writing about art and travel.

Placing the Osprey Notes on the Wharton map indicates the importance of classical Greece in Wharton’s quest for cultural continuity. In particular, an overview of the actual contexts of the trip suggests the trip is related to Wharton’s effort to grapple with her devastating experience of the Great War. Wharton’s nonfiction war writings have spurred a debate on her relation to cultural loss and modernism in general, and, as part of this, on what kind of feminine vision of the war behind the lines she represented (Kovács 2017, 545). If the Osprey Notes is considered from this perspective, I argue, the fragments of the notebook may reflect Wharton’s need for cultural and historical continuity after the cataclysm of WWI Jazz Age drifting is traditionally thought to be the result of.

1. The Wharton map at the intersection of traditions of writing travel

The reception of Wharton’s published travel writing locates her texts at the intersection of different traditions of writing travel. In The Cambridge Companion to Travel Writing, James Buzard surveys practices of the Grand Tour (1660-1840), and focuses on the search for the picturesque as a mediation between the beautiful and the sublime (Buzard 2002, 45) that lived on at the time of mass tourism after 1815, too (Ibid., 46) and eventually resulted in the traveler contra tourist dichotomy which “established a new paradigm suitable for the dawning age of tourism” (Ibid., 49). Helen Carr’s survey of modernism and travel continues to rely on the tourist vs. traveler dichotomy in the early nineteenth-century. Carr’s overview starts out with the assumption that the years 1880-1940 were the heyday of the British Empire and much travel writing shows complicity with imperialism (Carr 2002, 71). Yet, she also draws on Nicholas Thomas to propose that “imperialist ideology may have been more vulnerable, complex, and ambivalent than has been generally acknowledged” (Ibid., 71-2). She distinguishes three stages of writing about travel within this frame: realist instructive tales until 1900s, more subjective and literary accounts until before the Great War, and literary travel books between the wars about well-known areas showing new characteristics, pieces that raised the popularity of both travel and travel writing (Ibid., 75).

Carr refers to Wharton twice as an example. First, the golden calm of the pre-WWI period is illustrated by Wharton’s Italian Backgrounds that distances the mechanical sight-seer from the serious one (Ibid., 79), the tourist from the traveler. Second, in the interwar period, Wharton’s In Morocco is referred to as an ambiguous example of the colonial gaze, in which Wharton who admired French colonial administration and whose trip was made possible through it “writes regretfully about the loss of the Moroccan past”, so there seems to be “no simple hierarchy of the West and the rest: native arts are superior to Western vulgarity, even if the best of the West is superior to both” (Ibid., 82). From this generalizing perspective, Wharton’s Aegean notes from the interwar period are likely to bear the brunt of an ambiguous colonial gaze, motivated “by the fear that the rest of the world is losing its distinctive otherness” (Ibid., 81).

Sarah Bird Wright frames the intellectual and publishing contexts of Wharton’s travel writing without reference to the colonial frame in her Edith Wharton’s Travel Writing (1997). Instead she claims that Wharton’s travel writings are situated at the meeting point of distinctly different traditions of writing about travel and art. On the one hand, it was the picturesque tradition in the second part of the nineteenth-century that influenced Wharton’s thinking about travel and art. The aesthetic sensibility of cultured amateurs played the main role in these, opposed to the rapid lack of appreciation by tourists. On the other hand, a method of more scientific accuracy became accepted before the turn of the century, a trend Wharton also embraced (Wharton1990a, 890) but later rejected to return to Ruskin, Wright claims (Wright 1997, 10).

Wharton herself reflects on the problem of transitioning from the picturesque tradition of travel writing to a more technical one while working on Italian Backgrounds. In A Backward Glance she writes that aesthetic sentiments and impressions of art and travel by amateur cultivated travellers were to be replaced with technical accounts by trained scholars in the 1870s and 80s (Wharton 1990a, 890), professionals who did not deal in sentiments. The duality was to be transgressed by Bernard Berenson’s volumes in which the two were combined, and as Wharton comments: “lovers of Italy learned that aesthetic sensibility may be combined with the sternest scientific accuracy” (Ibid.). Wharton’s friendship with Bernard Berenson in her later life strengthened her desire for a mixed methodology “a field of observation wherein the mere lover of beauty can open the eyes and sharpen the hearing of the receptive traveller, as Pater, Symonds and Vernon Lee had done to readers of my generation” (Ibid., emphases mine). Although Ruskin’s name is not mentioned, the references to (precise) observation, seeing (differently) and hearing (the voice of the past) indicate a connection to Ruskin’s formal method of reading art as a connection between sentiments and technical detail.1 As a supplement to this, in her “Life and I” Wharton writes enthusiastically about her early encounter with Ruskin’s “cloudy pages” that “woke in me the habit of precise visual observation. The ethical & aesthetical fatras were easily enough got rid of later, & as an interpreter of visual impressions he did me incomparable service (Wharton 1990b,1084).

Wharton’s Italian Backgrounds indeed displays the effect of the clash between the earlier picturesque tradition of sentiments and scientific accounts of technical detail. On the one hand, as Wright shows, Wharton struggled with editorial expectations to write about picturesque scenes in Italian Villas. Also, in Italian Backgrounds Wharton challenges Ruskin’s adoration of the Italian Renaissance, to which she prefers and adds the Italian art of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries (Lasansky 2016, 154-5). On the other hand, Wharton’s precise observations are indeed influenced by Ruskin’s method of seeing, this is how she identifies the origin of Tuscan terracotta figures at San Vivaldo and challenges Ruskin’s canon of Italian art. No wonder Eleanor Dwight writes about Ruskin’s powerful influence on Wharton’s relation to art and architecture in general and to Italian architecture in particular (Ohler 2019, 21-2). Charles Eliot Norton also appears as a significant influence on Wharton’s relation to Italy. William Blazek argues for a threefold connection between Wharton and the ideas of Charles Eliot Norton’s Travels in Italy: “the importance of imagination as the central element of both artistic and social progress, the bond between aesthetics and morals, and the concept of service (Blazek 2016, 64). Expanding on these connections, Robin Peel connects Wharton’s immersion in Italy and writers about Italy to her “profound fascination with the mystical” (Peel 2012, 286).

The Ruskinian voice of the past to be heard by the traveler is also recorded in Wharton’s writings on France before and after WWI. Mary Suzanne Schriber wrote that the Great War turned Wharton’s travel writing on France from romance to nightmare (Schriber 1999, 143) as Wharton had to document the destruction of the architecture so precious to her. This accompanies the loss of the voice of the past from architecture parlante, especially notable in the case of ruined cathedrals (Kovács 2017, 559). Julie Olin-Ammentorp explains the significance of this further when she writes that for Wharton the war was fought for civilization (2004, 219) and “most if not all of Wharton’s post-war work can be seen as a meditation on the question of civilization” (2004, 220) (probably due to a fear of rootlessness (Olin-Ammentorp 2019, 264)), a cosmopolitan tendency Carol Singley attributes to Wharton’s search of moral consciousness influenced by Ernest Renan (Singley 2003, 42).

In Morocco sets out to record the presence of a medieval past in the French protectorate of Morocco. Wharton’s last travel book combines technical details of monuments with personal impressions of precious civilizations of the past encoded in architecture that shine out at the golden sunset hour (Kovács 2014, 63). The “picturesque opportunities” (Wharton 1996, vii) of the area are indeed used and, as before, architecture and art have a story to tell the observer about the past. From the perspective of the Orientalist drive of Wharton’s account that values the civilizing work of French colonial administration, her drive to preserve the Medieval past is ambivalent. Perhaps Wright’s transitionary model can be related to Carr’s description of the ambiguous colonial gaze in In Morocco: the individual variation in the colonial gaze may have to do with the return of the sentiment in the style of the Moroccan travel text in 1920.

The directions in Wharton reception situate the place of the Osprey Notes at the intersection of traditions of travel writing, art history, and theories of culture. It has been shown books and ideas about art and culture by Ruskin, Norton, or Berenson constitute cornerstones of Wharton’s theory of culture and art. Drizou’s reading of Wharton’s travel accounts to modern Greece in which “tropes of wandering and homecoming […] construct a symbolic narrative of return to the Greek ideals of human, historical, and cultural connectedness that Wharton sees missing in her contemporary modernity” (72) delineates the phenomenon of cultural nostalgia in a very precise way, with a focus on the trope of the Odyssey. The question to explore further is in what terms the cultural nostalgia is formulated. It is tempting to ask how the picturesque and the scientific traditions are combined in her notes of 1926 and whether any trace of the ambiguous colonial gaze is palpable there. Before looking into this question, let us briefly chart the temporal and geographical parameters of the cruise first.

2. Sources for reconstructing the itinerary of the Osprey and the scope of the Osprey Notes

The itinerary of the Osprey can be traced not so much on the basis of the Osprey Notes but rather by relying on extra documentation. First and foremost, Wharton’s autobiography A Backward Glance (Wharton 1990a, 1058-60) points out the significance of the cruise and its relation to the 1888 visit to the Aegean. Yet, this account articulates the significance of the journey to Wharton rather than its particulars. Various biographies also help to chart the scope, if not the details, of the enterprise. In terms of dates and sites and impressions, it is Margaret Chanler’s Autumn in the Valley (1936) that provides the most practical information about the design of the journey and also about the kind of art historical running commentary the connoisseur travellers must have made during their visits to sights. Last but not least, Wharton’s 1888 diary of the cruise with the Vanadis help the work of reconstruction in that some of its chapters overlap with the Notes. Wharton’s letters also provide clues about her experience, if not the details, of the trip.

Itinerary 1: Daisy Chanler’s Autumn in the Valley

Between April 1 1920 and May 30 1926 the Osprey took five travellers around the Aegean and the Easter Mediterranean. The party boarded the yacht in the port of Hyères, Wharton refers to the group as pilgrims in The Backward Glance. They cruised around the Peloponnesus by way of Sicily, they approached Athens through the Corinth channel, and in May they travelled around the islands of the Dodecannesos from Aegina to Delos and Naxos through Rhodes and Crete in search of places Daisy Chanler called “ancient shrines of beauty” (Chanler 1936, 242).

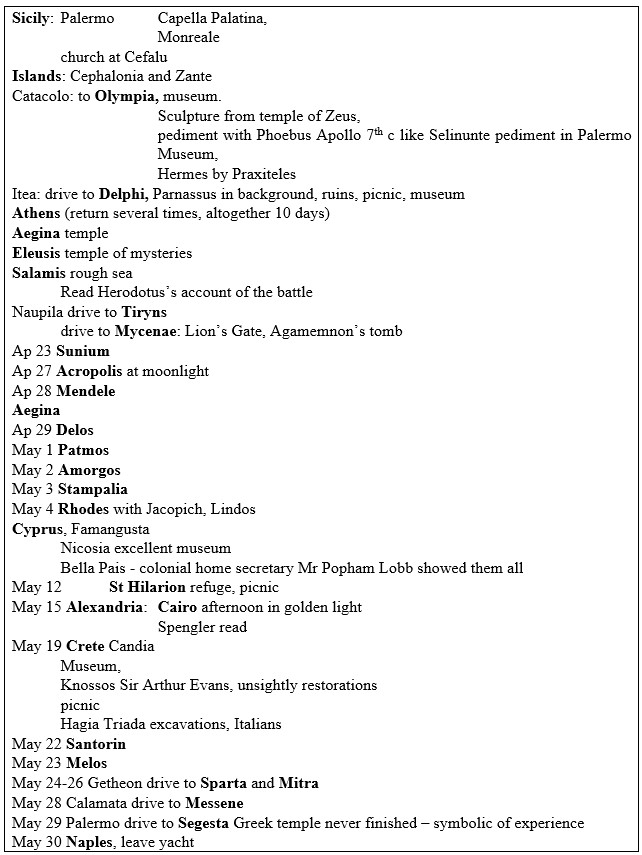

Chanler’s autobiography provides a detailed overview of the sites and highlights of the trip (dates are not always given).

Table 1: The itinerary according to Chanler’s account

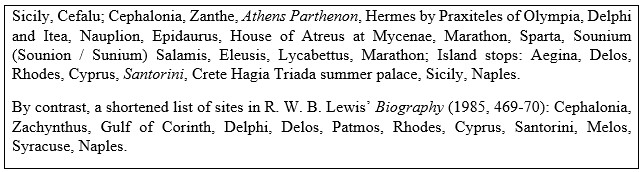

Hermione Lee’s biography charts the sites in a slightly different order. After the islands of Cephalonia and Zante she enlists Athens and the Parthenon and Olympia and Delphi afterwards, followed by the sites visited while returning to Athens repeatedly for fuel. Among the islands, Lee lists Santorini before Crete (Lee 2007, 643), and highlights the important moment of Wharton at the creek in Crete she remembered in her last letter to Berenson (Lewis and Lewis 1989, 602-3).

Table 2. A. List of sites visited in Lee with variation to Chanler in italics:

Chanler’s account proves to be a valuable source not only because it provides basic information for the reconstruction of the itinerary. It is also useful because it inspires ideas about the conversations that might have been made during the excursions or on the board of the Osprey, as her comments overlap with Wharton’s notes. Similarly to Wharton, Chanler discusses the stupid looking charioteer at the museum in Dephi (Chanler 1936, 217), the timeless beauty of the Acropolis (Ibid., 218), the lack of mystery at Eleusis (Ibid., 221), even the experience of the Acropolis at moonlight (Ibid., 220). In addition to what Wharton says, Chanler emphasizes the learning that went into the arrangements and excursions: she writes about reading Herodotus’ account of the battle at Salamis when rough sea prevented the landing (Ibid., 221-2), the bookshelf of the Osprey and the importance of The Odyssey for the party (Ibid., 211-2). The account also features a strong comparative aspect, a readiness to juxtapose items of art visited, for instance the pediment of Phoebus Apollo at the Museum of Olympia with its Sicilian Selinunte counterpart (Ibid., 216) or the behive structure of the tomb of Agamemnon at Mycenae to the roof of the sacred grotto at Delos (Ibid., 222-3). In addition, Chanler loves to refer to the beauty of sights, the effect of the light on the scenery, for instance at the Acropolis. Her final remark reveals an intention to induce others to travel and experience beauty (Ibid., 241-2). All in all, Chanler’s account reads like a scholarly handbook version of the encrypted Notes of the journey.

Itinerary 2: Wharton’s Notes

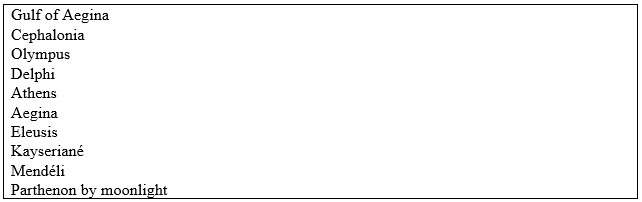

Wharton’s notes are comprised of 10 fragments on handwritten pages. The entries are not dated, they are headed by locations that can be linked to Daisy Chanler’s itinerary. The headings do not all conform to Chanler’s ones.

Table 3: Wharton’s headings

When compared to the full itinerary reconstructed above, it becomes obvious that the notes cover only a small portion of the actual cruise, namely the visits between the island of Cephalonia and the days in and around Athens. Possibly, the writing of the entries began after arriving at Athens as the sea of Aegina is described by reference to sculptures at the Parthenon. Also, the final entry ‘Parthenon by moonlight’ must be either a reference to the evening Daisy Chanler also remembered fondly from April 27 (Chanler 1936, 220) or the day after when they visited again, so the coverage ends before sailing for the Aegean islands.

Wharton’s diary about her first Aegean cruise converges with the second journey and the Osprey Notes. In 1888 the cruise started with a North African leg from Algiers to Malta before setting out for a trek around Sicily. Then the company visited Corfu, Cephalonia, Zante, proceeding to the Aegean islands right after, through Milo, Santorin, and Rhodes. From Rhodes they went North to Smyrna, Mytinele and back to Mt. Athos before arriving at Athens and Corynth. Then they cruised the Albanian and Dalmatian shore, finishing the trip with Zara. They left the ship at Ancona. The cruise of the Vanadis partly overlapped with the itinerary of the Osprey: both included the Ionian islands and the Aegean islands, and the trips to Athens and her surroundings. As for the textual connection, there is also overlap in terms of Wharton’s actual entries, there are sections in both texts on: Athens (sections on Gulf of Aegina and the view from the Acropolis), The Ionian Islands (Corinth, Eleusis).

3. Attic shapes past, present, absent: continuity and picturesque scenes in the Osprey Notes

The ten fragmented passages of the Osprey Notes represent different levels of picturesque description. Three entries are practically empty: Cephalonia (1) and Athens (5) are short notes about the itinerary only, while ‘The Parthenon by moonlight’ (10) contains no text at all, it presents only a title. Among the remaining seven entries one can find full descriptions of seascape or landscape, architecture, vegetation and in some cases also the impressions these scenes make. On the basis of the quantity of reflection, it is the Delphi (4) and the Mendéli (9) segments that stand out as the fullest, while the description of the gulf of Aegina (1) Olympia (3), Kayseriané (8) and Eleusis (7) contain some features of what I would like to call Wharton’s ‘picturesque scene.’

The Delphi (4) note presents a picturesque scene in detail. The passage begins with the travellers watching the land from the yacht, then landing at Itea, in the bay underneath the hills of Delphi, taking in the view of the olive orchards of Apollo, of the bay, of the mountains with snow on the top. Then follows the visual description of the ascent to the shrine, the elevation leading to commentary: “Unimaginable beauty — up and up.” (Delphi). Moving closer, the landscape and the ruins are named and described until a quiet sort of verbal ecstasy is reached: “Below the spring we lunched under huge olives on the slope just above the ruins of the Gymnasium, where the great circular swimming-pool is still well-preserved. All was beauty, serenity and awe. A matchless landscape.” (Delphi) In other words, the scene is watched, the visual image is considered and taken in to be measured up in the form of an evaluative impression. The account of an afternoon stroll that repeats the elements of the first impression but the evaluative part is not repeated, only the visual. Finally, an additional sober sequence breaks the awe of the fragment about items of art at the museum that cannot compare to the Apollo of Olymp.

The Mendéli (9) fragment represents a visit to Mendéli monastery that also reports about an experience of beauty. In this note, the description of the approach to the monastery begins with the identification of the hills and elevations, and is then punctuated by the view of the actual monastery. The complete and prosperous shape of the buildings offers no picturesque quality, yet “there is beauty” in the symmetry of the building, its relation to the vegetation and to the silver water flowing by the building. The valuable impression of the landscape is collected during a walk above the monastery in the hill, the view of the orchards and forest, hills, plains, sea (all identified by name), a new story at every turn. As a culmination point, Wharton reflects: “What a landscape!”. As an addition, she identifies the impression through a literary allusion to Keat’s “Ode on a Grecian Urn”: “As we returned, the air was full of sweet bells, and a flock of black goats with undulating horns came down the hill tended by a tiny boy and girl, and followed by a flock of honey-brown sheep with long hieratic fleeces. – „O little town??…” It was all saturated with Keats.” The timeless quality of the picturesque scene is not spelled out explicitly, only the reference to the scene as similar to the one on the urn in Keats, which implies Keat’s sense of timelessness:

"Thou, silent form, dost tease us out of thought

As doth eternity: Cold Pastoral!

When old age shall this generation waste,

Thou shalt remain, in midst of other woe

Than ours, a friend to man, to whom thou say’st,

"Beauty is truth, truth beauty,—that is all

Ye know on earth, and all ye need to know.""

The Attic shape of the typically Greek picturesque scene evokes an impression of the Romantic notion of timeless imaginative beauty in the observer.

In the companion piece to this fragment, Kayseriané (8), the impression of security and dreams created by the picturesque scene is explicated by the image of the beehive.

"No view, but huge shady plane trees in the outer court, and the usual impression of coolness, meditation, security and dreams. Very picturesque inner courts, wildly irregular with deep archways, overhanging loggias, old crumbling stone stairways, and the low-arched cloister preceding the little church, so honey-brown, domed, embroidered, with comb-like traceries, that it might have been made by the bees, the celebrated bees of Hymettus – and the monks after all might be compared to them, with their patient building-up and their storing of sweetness, in all the wild warring times." (Kayseriané)

The building of the church looks like a beehive, and also functions like a beehive in the image: the monks are identified with bees and are storing sweetness of the peace of the past at the wild “warring” time of the present.

The fragment about Eleusis explains the quality of the saturated impression of the peace of the past further. The approach and the landscape and ruins are described here as well, but, surprisingly, the lack of vegetation and of water results in the comment that the effect is useless: “not mysterious enough. There are no trees, no waters, to help one to dream back into the past.” (Eleusis, Wharton’s emphasis). It follows from this that the impression created by the approach, the view, the landscape, the vegetation and the water serves a definite purpose: it is supposed to help the observer, “dream back into the past,” imagine to be present in the past for a short mysterious moment in time. Again, this is an instance where a picturesque scene could mysteriously evoke the timeless harmony of ancient Greece like it did in Keats’s poem. Unfortunately, the model is present only in its absence, as Wharton laments the lack of the experience this time, but even this absence helps one assess the expected content of what I would call “Wharton’s picturesque scene”: arrival at a place with a view, lush vegetation, some form of water, and an added moment of reflection on the continuity of the past.

Unfortunately, the entry on the Parthenon is missing from the Notes although it would undoubtedly be an ideal site for a picturesque scene and an experience of continuity between past and present. Therefore, it comes as a disappointment that there is only the promising heading “The Parthenon by moonlightMoonlight on the Parthenon.” that ends the notebook. It makes one ask how moonlight at the scene might enhance the mystery of the presence of past harmony at the Parthenon, as Wharton observed it. Regrettably, the Parthenon is only referred to earlier, via its horses and other sculpture when the waves of the gulf of Aegina are described in the first entry.

Conclusion

Edith Wharton’s manuscript notebook about her 1926 cruise to the Aegean and the Eastern Mediterranean extends the Wharton map geographically. Its picturesque descriptions of natural sceneries are coupled with an additional element of emotional response as well. Conceptually, the Osprey Notes can be linked to Wharton’s return to Ruskin’s precise observation as a method of describing nature. The descriptive look I would like to call “Wharton’s picturesque scene” focuses on sites where a sense of historical continuity can be reconstructed as an emotional experience, and eventually becomes a memory.

However, it has to be acknowledged that the Notes is a fragment that gives little evidence about wider post-war concerns such as a position on changing gender roles or colonialism. It is fragmented in several senses as it is partial, cursory, full of implication. It would be challenging to reconstruct the missing ‘Acropolis’ scene of the text with the help of external documentation. Perhaps with the help of additional letters or texts, this work of critical reconstruction can be performed later on.

Works cited

- Blazek, William. 2016. “’The Very Beginning of Things’: Reading Wharton through Charles Eliot Norton’s Life and Writings on Italy.” In Goldsmith, Meredith, Orlando, Emily J., and Campbell, Donna M., eds. Edith Wharton and Cosmopolitanism. Gainesville: University Press of Florida. 62-86.

- Buzard, James. 2002. “The Grand Tour and after (1660-1840).” In Peter Hulme and Tim Youngs, eds. The Cambridge Companion to Travel Writing. Cambridge: CUP. 37-52.

- Carr, Helen. 2002. “Modernism and Travel (1880-1940).” In Peter Hulme and Tim Youngs, eds. The Cambridge Companion to Travel Writing. Cambridge: CUP. 70-86.

- Chanler, Margaret Terry. 1936. Autumn in the Valley. New York: Little, Brown and Co.

- Drizou, Mirtou. 2019. “E dith Wharton’s Odyssey.” In Rattray, Laura and Jennifer Haytock, eds. A New Edith Wharton Studies. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 65-79.

- Goldsmith, Meredith Orlando, Emily J., and Campbell, Donna M., eds. 2016. Edith Wharton and Cosmopolitanism. Gainesville: University Press of Florida.

- Hewison, Robert. 1975. Ruskin: The Argument of the Eye. Princeton: Princeton University Press. Web. http://www.victorianweb.org/authors/ruskin/hewison/1.html Access: July 10, 2020

- Kite, Stephen. 2017 (2012). Building Ruskin’s Italy: Watching Architecture. New York: Routledge.

- Kovács, Ágnes Zsófia. 2017. “Edith Wharton’s vision of continuity in wartime France.” Neohelicon 44:3, 541-562.

- ——. 2014. “The Rhetoric of Unreality: Travel Writing and Ethnography in Edith Wharton’s In Morocco.” In Eleftheria Arapoglou, Mónika Fodor and Jopi Nyman, eds. Mobile Narratives: Travel, Migration, Transculturation. New York: Routledge. 58-69.

- Lasansky, Medina D. 2016. “Beyond the Guidebook: Edith Wharton’s Rediscovery of San Vivaldo.” In Goldsmith, Meredith Orlando, Emily J., and Campbell, Donna M., eds. Edith Wharton and Cosmopolitanism. Gainesville: University Press of Florida. 132-165.

- Lee, Hermione. 2007. Edith Wharton. London: Vintage.

- Lesage, Claudine. 2004. (1992) “Introduction.” In The Cruise of the Vanadis. Ed., intr. Claudine Lesage. 2004 (1992). London: Bloomsbury. 19-24.

- Lewis, R. W. B. and Nancy Lewis, eds. 1989. Edith Wharton: Selected Letters. New York, Macmillan.

- Lewis, R. W. B. 1985 (1975). Edith Wharton: A Biography. New York: Fromm.

- Ohler, Paul. 2019. “Creative Process and Literary Form in Edith Wharton’s Archive.” In Rattray, Laura and Jennifer Haytock, eds. A New Edith Wharton Studies. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 15-31.

- Olin-Ammentorp, Julia. 2019. “Questions of Travel and Home.” In Julie Olin-Ammentorp, Edith Wharton, Willa Cather, and the Place of Culture. Lincoln: Nebraska UP. 258-304.

- ——. 2004. Edith Wharton’s Writings from the Great War. Gainesville: University Press of Florida.

- Peel, Robin. 2012. “Wharton and Italy.” In Rattray, Laura, ed. Edith Wharton in Context. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 285- 292.

- Rattray, Laura, ed. 2012. Edith Wharton in Context. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Rattray, Laura and Jennifer Haytock, eds. 2019. A New Edith Wharton Studies. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Ruskin, John. 1886 (1849). The Seven Lamps of Architecture. Sunnyside: John Allen. (5th ed.)

- Schriber, Mary Suzanne. 1999. “Fighting France: Travel Writing in the Grotesque.” In Clare Colquitt, Dusan Goodman, Candance Waid, eds. A Foreward Glance: New Essays on Edith Wharton. Newark: University of Delaware Press. 139-148.

- Singley, Carol J. 2003. “Race, Culture, Nation: Edith Wharton and Ernest Renan.” Twentieth Century Literature 49: 1, 32-45.

- Wright, Sarah Bird. 1997. Edith Wharton’s Travel Writing. New York: St. Martin’s.

- Wharton, Edith. 2018. “America at War” trans. Virginia Ricard. TLS Feb 18, 2018, 3-5.

- ——. 2011. Back to Compostela: The Woman, the Writer, the Way: Edith Wharton and the Way to St. James / Regreso a Compostela: La Mujer, la escritora, el Camino: Edith Wharton y el Camino de Santiago. Ed. and trans. Patricia Fra López. Santiago de Compostela: Universidade de Santiago de Compostela, Servizo de Publicaciónes e Intercambo Científico.

- ——. 2004 (1992). The Cruise of the Vanadis. Ed., intr. Claudine Lesage. London: Bloomsbury.

- ——. 1998. “Les Oeuvres de mme Lyautey ou Maroc.” Tulsa Studies 17:1, 23-27. Originally published France-Maroc 2 (1918): 306-8.

- ——. 1996(1920). In Morocco. Hopewell: Eco Press.

- ——. 1990a. A Backward Glance. In Cynthia Griffin Wolff, ed., intr. Edith Wharton: Novellas and Other Writings. New York: The Library of America. 771-1068.

- ——. 1990b. “Life and I.” In Cynthia Griffin Wolff, ed., intr. Edith Wharton: Novellas and Other Writings. New York: The Library of America. 1071-1096.

- ——. 1926. Osprey Notes. Box 51 folder 1535. Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University.

Notes

1 Ruskin uses the analytic skills of the natural scientist in his readings of painting and architecture, and in both areas he tries to go beyond the surface of the picturesque. He shows that “even those things which seemed mechanical indifferent, or contemptible, depend for their perfection upon the acknowledgements of sacred principles of faith, truth, and obedience” (Ruskin 1886, 7). His accounts of architecture from the 1850s-80s describe layers of stone, eventually telling the life story of a building. Buildings of the Gothic and the early Renaissance present the most organic examples of such architectural stories. Although Ruskin relies on several disciplines in his observations, as Sephen Kite in Building Ruskin’s Italy puts it, he never identifies with any of them, he remains an amateur. Ruskin’s descriptions focus on not only the visual and tactile description of a building but also the emotional effect and the moral or religious values the work carries (Kite 2017, 8-9). Robert Hewison in his Ruskin: the argument of the eye claims that in Ruskin’s visual imagination each fact finds its place in three orders of truth: truth of fact, truth of thought, and finally the truth of symbol (Hewison 1975). Kite puts this more directly when he says that Ruskin provides visual, imaginative and moral/religious readings to the “facts” he describes (9). ↩

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.