Michelle Obama’s Becoming represents an ultimate dream: the story of a working class African American girl who becomes the first lady of the US. Although the book develops a special American rags to riches plot, the story covers not only the journey of becoming the First Lady, but also that of becoming a person with a voice and a project. In Becoming this project means a focus on change on many levels. I argue that ‘change’ in the text has both personal and political implications: I want to focus on how the personal and political senses of the term are represented in the autobiographical narrative. In order to look into the representations of change in the text, the paper investigates where the text comes from, what its modes of existence are, what subject positions it determines, how it is circulated.

In his A Home Elsewhere: Reading African American Classics in the Age of Obama Robert B. Stepto compares Barack Obama’s memoir Dreams from my Father to classics of African American literature (Stepto 2009a, 2). Texts by Frederick Douglass, James Weldon Johnson, W. E. B. DuBois, Zora Neale Hurston, and Toni Morrison are read along with Obama the literary author, revealing long lines of connections. As Stepto writes: “[t]hese are age-old themes in African American literature that have special poignancy and importance at the moment because […] Obama’s narrative […] refreshes and our readings and recollectionas of the whole of African American literature” (Stepto 2009a, 5). Eric D. Lamore follows up on Stepto’s project by drawing attention to the importance of the autobiographical tradition in African American writing (Lamore 3), a loose genre into which Barack Obama’s first book also belongs. With reference to them, my idea is that in Michelle Obama’s Becoming the story of finding one’s voice relies heavily on a body of African American writing about constructing one’s agency by transforming one’s self.

On the one hand, Becoming can be read as self-narration and political commentary in the sense of antebellum autobiographical slave narratives which had aimed to trigger political change by personal testimony. In the old slave narrative, the testimony came from a reliable source who had shaped his/her life in a way to accommodate different notions of freedom, from psychological to political. In Becoming, Michelle Obama tells the story of her life in order to show us that personal, social, and also political change is indeed possible to attain. For her, the question is not if change can be reached but rather how it is to be realized, so ‘change’ is shown to be a methodological question. The meticulous analyses of witty anecdotes in the book give us a hand in understanding how change of all sorts can be achieved most efficiently, a method to be learnt easily. Therefore, in this rags to riches story the main issue is not so much the success attained but the kinds of change that have brought success about. On the other hand, another intertextual influence is African American women’s fiction where the theme of finding one’s voice in the context of double oppression is vital. Perhaps the most famous fictional heroine of this type is Janie from Zora Neale Hurston’s Their Eyes Were Watching God, who runs away from her possessive husband into the arms of another just as possessive, where she learns that the way out of the situation is not running but using the language of the oppressor and fighting back verbally. By the end of the story and after the death of her third husband, Janie is actually able to tell her own story of how she learnt to articulate her opinion and aims. Patricia Hill Collins calls these kinds of narratives stories of black women’s empowerment (Collins 2). Becoming can be read as personal testimony of African American female empowerment as well in that it maps out possible routes of African American feminine ‘development’ or change.

Despite the strong focus on trajectories offered by black women’s lives, the subject positions determined by the narrative are not limited to women of color. Originally, antebellum narratives were written for the sake of the white audience, usually propped up by a Preface from a respected white editor. In Becoming there is no need for and editorial voice to introduce and appraise the author whom everybody knows as the ex- First Lady. Yet the book is similar to the old narratives in that it is written not only for the African American but just as much for the white American audience. Also, the global circulation and consumption of the book ensures that its story reaches an international readership. Michelle Obama makes her story of change visible and understandable that serves to motivate all the readers who can relate to it either on a personal, social, or political level.

1. Origins

The summary of the basic milestones of Michelle Obama’s life can help us locate the parallels between the text and African American autobiographical writing. Main events highlighted include references to family relations, the importance of education, and life turning events that feed into a story of psychological transformation, almost self-help. Michelle Robinson comes from a typical working class African American neighborhood in Chicago’s South Side. Her parents brought her up in a modest one-bedroom apartment on the top of her great aunt’s house. Her ticket to middle class existence was education. She learnt to read before going to school, and gave evidence of her skill on the first day in class, with a degree of success:

"When it came to my turn to read the words off the teacher’s manila cards, I stood up and gave it everything I had, rattling off “red,” “green,” and “blue” without effort. “Purple” took a second, though, and “orange” was hard. But it wasn’t until the letters W-H-I-T-E came up that I froze altogether, my throat instantly dry, my mouth awkward and unable to shape the sound as my brain glitched madly, trying to dig up a color that resembled “wuh-haaa.” It was a straight–up choke." (18)

Next day she asked for a do-over and showed she could read the tricky word “W-H-I-T-E” as well as all the best of the others.

In second grade she and some classmates were removed to a special class for high achieving kids. This became necessary because their form teacher had given up teaching and disciplining the kids in her class. Michelle’s mother complained about the level of education, and after a month’s worth of hassle the transfer was eventually completed, and she excelled in the new, project oriented environment. At 14, she was admitted to a reform magnet high school where she again shined, and despite a careers advisor’s advice that she was “not Princeton material,” she was accepted to Princeton, where she majored in sociology. Then she attended Harvard Law school and eventually got a job as a lawyer at Sidley Austin, a prestigious law firm in Chicago, earning a six-digit salary as a 24-year-old beginner. Throughout the book, Obama describes the strategy behind her success as a belief in the effort-reward connection (92). Her piano lessons at the age of four with her great aunt the piano teacher, and also the ones she listened to through the wall to her aunt’s apartment, convinced her early on that every effort brings its reward, that practice comes with success and approval. This conviction explains her willingness to put in long stretches of work for achieving a desired aim, her propensity for setting long term-goals that need extensive preparation. She talks of herself as a “detail-oriented person” (191) who draws pleasure from setting goals, of box-checking and monitoring progress (89, 190). Setting aims and ticking off the result of work also brings the fringe benefit of feeling in control of events (232).

It was Michelle’s meeting Barack Obama at Sidley’s that made her question the simple cause-effect idea of the effort-reward continuum. Barack, though a brilliant trainee lawyer, did not show interest in the material rewards being a lawyer meant. Instead of signing up for a good salary and networking, he was interested in how the life of a given community could be better organized. Early on in their relationship, Barack took Michelle along to a community meeting at a local church, where his task was to persuade locals to start up projects concerning their neighborhood (116). The difference between her own and Barack’s notion of social mobility had dawned on Michelle earlier already (101-105), but now listening to him, she also became committed to Barack’s idea. She understood that instead of material rewards of mobility, Barack was interested in mobility because he saw it as a way to become more efficient in implementing change.

"He was there to convince them that our stories connected us to one another, and through these connections, it was possible to harness discontent and convert it to something useful. …

His voice climbed in intensity as he got to the end of his pitch. He wasn’t a preacher, but he was definiely preaching something – a vision. He was making a bid for our investment. The choice, as he saw it, was this: You give up or you work for change. … ”Do we settle for the world as it is, or do we work for the world as it should be?”" (116, emphasis mine)

Barack’s vision was so powerful and persuasive that Michelle herself reacted to it approvingly, along with members of the local community.

The realization of the existence of different possible rewards to personal effort changed Michelle’s own life as well. She felt her professional life as a lawyer was without real significance, so she initiated a change in her career trajectory in order to engage in jobs where she felt her job mattered. She looked out for more community oriented work, following the example of inspiring African American women she knew like Susan Sher and Valerie Jarrett (151); they worked with principles Michelle also endorsed like Valerie’s Franklin-sounding tenet “[i]nspiration on its own was shallow; you had to back it up with hard work” (158). First, Michelle worked for Chicago City Hall for Valerie Jarrett in the mayor’s office as a liaison to other departments (Chotiner 2019), then as an assistant commissioner in charge of planning an economic development. Then she was the head of the nonprofit organization Public Allies that gave grants to talented locals to train them for jobs in facilitating work contexts. Later on she joined the University of Chicago Medical center to develop the contact between the university and the community of the South Side, where it is located. This was the job she left as the wife of the Democratic presidential candidate sometime in 2007.

2. African American autobiographical discourse in Becoming

When reviewing the sources of this rags to riches core narrative about change, the primary influence is obviously the African American autobiographical tradition. More specifically, a basic input can be located in the genre of the slave narrative which serves as the blueprint for different kinds of first person life writings in the African American literary context.

“Autobiographical narratives of former slaves,” W. L. Andrews writes, “comprise one of the most extensive and influential traditions of African American literature and culture” (12). The slave narrative is the first person narrative about the life of an escaped slave who has become free through luck and his or her own work, against all odds. Becoming free happens on several levels: the geographical mobility from the South to the North is paralleled by economic freedom to sell one’s labor. In addition, the psychological movement from seeing one’s self as free psychologically is presented coupled with a religious idea of freedom (Andrews 25) or conversion, and political ideas of freedom as well (Gould 17). The story of becoming free develops the theme that the narrator possesses a human self, a key issue of slave narratives (Andrews 26). The early eighteenth-century type of the slave narrative is practically a dual conversion and slave narrative, while the nineteenth-century version documents the evils of slavery to initiate political change. Both types share a handful of features. As testimonies, they are written in the first person, they relate the story of a conversion or resurrection from and old slave life to a new free life. A key element of breaking free is education, learning to read and write. Family relations (or their lack) are always made clear as a start. Physical and psychological tribulations of slaves at the hands of whites are enlisted, some of which function as sentimental or tear jerker elements aimed to shock readers (Gould 11). Writing by male and female ex-slave show a difference in concerns: most notably the role of family relations, especially motherhood, are presented differently (Andrews 26). As these narratives were to be read by a white audience to be won over to sympathize with the teller, the criticism of the white race was subtly calculated, the most horrendous tribulations deftly not told, were left as gaps (Morrison 1995, 90). All was written up in a highly polished style that pleased middle class white readers.

The slave narrative form was widely appropriated by African American authors of the 1970s-80s, an intertextual gesture that draws attention not so much to generic features but the social functions slave narratives have. Ashraf H. A. Rushdy has studied a range of novels form the 1970s and 1980s that have relied on the form of the slave narrative to ask the ‘why’ question: to consider the social significance of the fact that the inert nineteenth-century genre was being re-used in the aftermath of the Civil Rights Movement. As he explains, his method surveys the determining forces behind the interplay of factors normally called ‘tradition:’

"[w] e need to return the social to the literary when we explore how authors establish intertextual relationships with their predecessors as part of the strategy of revisionist striving for canonicity. Such an analytical method should prevent us from succumbing to the allure of a stable literary tradition, instead provoking us to search out the determining forces behind the impetus for constructing “traditions.” Since the “function of traditions” is to create the illusion of “unity out of disunity and to resolve, if not make invisible, the social contradictions or differences between texts,” our job as scholars of minority literatures should be to expose rather than perform that function." (Carby 42)

Rushdy surveyed the social cultural roles neo-slave narratives played by appropriating the form of the slave narrative. He studied texts he called neo-slave narratives as cultural products of a discursive formation in order to explore what social contradictions they sought to resolve or mask. In the case of Becoming, the rationale of comparing the text to nineteenth-century slave narratives can be similar to Rushdy’s project. The social-cultural significance of the story of an emerging self that uses the form of the slave-narrative can be charted in order to explore what social contradictions it ‘seeks to resolve or mask’ (ibid.).

Becoming proudly marshals several of the above features of the slave narrative. It is a first person narrative emphasizing family ties at the outset. It stresses the importance of education in transforming one’s life, even contains the scene of learning to read as a way to ‘freedom’ as experienced by Michelle the narrator (cf. the episode with reading ‘W-H-I-T-E’). It highlights the element of change as a key to improvement, i. e. ‘freedom,’ in life. It is full of anecdotes with morals about this ‘freedom.’ Also, one can detect some glossed over gaps, for instance the story of the Harvard years. Last but not least, the element of conversion is also present, not so much in a religious, but rather in what looks like a political sense first.

Instead of a checklist of items to be compared, let us focus on the conversion element of the slave narrative. I argue that the old theme of ‘conversion’ appears in Becoming as the issue of ‘change.’ Of course, this theme is connected to Michelle meeting and falling in love with Barack Obama. So I also claim that the love story reads as a story of conversion. In the scene at the community center looked into before, Michelle was won over by the vision Barack communicated, the idea that change needs to start with the individual whose actions matter for the community. Adopting this idea means a change in Michelle’s idea of social mobility. So far she had been intent on making efforts for material rewards, individually, while Barack’s notion of mobility requires mobility for the sake of the community and as a tool for change. This is a second sense a mobility that comes from Barack, referred to as mobility as obligation (101), which transforms Michelle’s first sense of individual mobility into a communally oriented sense of social mobility.

Mobility for the sake of the community and change from the level of the individual, from bottom up – this sounds political. It is also reminiscent of Barack Obama’s political slogans from later on in his political career. Yet, in many disparaging comments, Michelle makes clear how much she dislikes politics as a party level institution. Her dislike starts from her family’s distrust of politics as white people’s game to prevent the advancement of colored people and stretches to personal experiences of ruthless political interests in the face of individual values. Not surprisingly, she does not even fancy the idea of her husband becoming a politician (151) let alone a presidential candidate (224-5). However, when she was won over to the idea change from the bottom up for the community, she was into politics in a wider sense.

In an article in The New Yorker, Amy Davidson Sorkin discusses Michelle Obama’s ambivalent relation to politics. Sorkin comments on Michelle’s disparaging remarks on politics in the face of her commitment for engaging jobs and change, alluding to the fact that the account is political in a wider sense than that of party politics (Sorkin). It is political in its preference of mobility for the community, to which Michelle has been converted through her “love for her husband” – the title of the article refers to. So despite her dislike of party politics, Michelle Obama’s devotion to change and social justice seem political in the general sense that it is aimed at transforming the life of the community as well as that of the individual. This also resonates with Valerie Jarret’s general idea of political power that “comes from the bottom up” (Chotiner) Michelle interiorized early on.

The conversion aspect of slave narratives is also present in the text as the act of reinterpretation. Incidents of Michelle’s life as a girl are reconsidered from the new perspective of mobility for the community. She reflects on her removal from the useless second grade class to the special one as an extra opportunity and adds a concern about the rest of the class who remained in the old room with the incompetent teacher. What became of them? Surely they did not become graduates of Ivy League schools. – Similarly, she considers the case of the careers advisor who told her she was not Princeton material and she reflects on the negative stereotyping against high achieving working class colored students by professionals whose work should be to work against such stereotyping. Also, she remembers her father’s prolonged illness without medical care of any sort and final ten days in hospital when he was already beyond any help — she wonders how many others suffer from the same lack of basic healthcare.

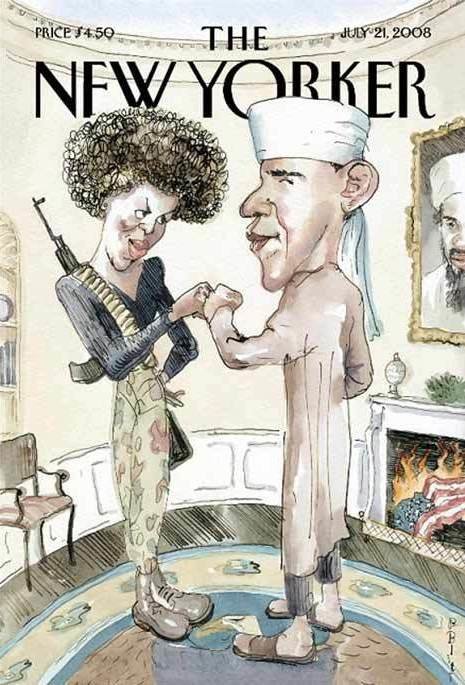

As the above examples indicate, the new perspective of mobility for the community enables the reinterpretation of limiting racial expectations as well. Obama calls these limiting racial expectations simply “the American gaze” (250, 252, 372). Throughout the text, ‘the American gaze’ means simplifying ready-made biased role models applied to colored (mostly female) characters. Michelle is in the lead role again: after enlisting the roles of colored students in Ivy League educational institutions, she confronts her readers with the ready-made expectations towards the African American wife of an African American Democratic presidential candidate. In many media reports, she was portrayed through the cliché of the angry black woman (264), the militant heiress of the Civil Rights movement, not patriotic, belonging to radical black church, like on The New Yorker cover image below she chooses not even to mention.

In this area, her reinterpretation of the negative social and racial stereotypes takes the form of personal testimony and performance. She is intent on planning new roles for herself. She started practicing this well before becoming the First Lady: this was the reason for opting for meaningful community oriented jobs, that is why she took part in her husband’s presidential campaigning actively, and that is why she also reinvented the roles of the First Lady, who, as we learn, has no actual job description (295), just an expected one that actually is a distraction from the “impactful work” she had in mind (309). So as the First Lady, she also starts her initiatives: healthy food for kids, the importance of sports in life, integrational programs for families of professional soldiers, and educational opportunities for girls.

3. Subject positions: Black Feminism and Empowerment in Becoming

The second source for the theme of change and telling one’s story is the vast body of literature and criticism by African American women. The female character learning to use her voice to act out her agency is a basic recurring theme in literature by African American women. We all remember Zora Neale Hurston’s Janie in Their Eyes Were Watching God, who lost three husbands but learnt to use her voice for articulating her opinion and destroying those of others limiting her. We all recall how Celie began to write and tell her story in Alice Walker’s The Color Purple to end up with a vocation, a voice, and a new gender identity. Another example can be Toni Morrison’s God help the Child. Its coal black female protagonist has fashioned herself into a successful businesswoman wearing only white clothes to enhance her black skin — but even she has to undergo change, and learn to speak up, to process. In all these stories, gaining possession of one’s voice is necessary for constructing one’s agency.

Before returning to additional features of the African American women’s writing, let us insert a remark. The casual reference to Morrison’s Bride from among the hundreds of other possible examples has not been purely coincidental. Morrison’s heroine was referred to because of the way her clothes relate to Michelle Obama’s new style. Michelle Obama has begun to show a preference for soft style white dresses around the time of her book tour, as one of her commentators remarked:

"Gone are the Gap-holiday-advert rainbow-bright colors, the neat pencil skirts and cute gingham checks, the school-fair-cake-stall J Crew cardigans. Instead, she is luminous and serene in all white, refined and elegant in wide trousers and silky tailoring. On stage on Monday evening, she looked positively angelic in a long white jumpsuit." (Cartner-Morley)

Michelle’s soft white dresses highlight her successful brand of blackness the same way they did for Bride in Morrison’s novel, drawing attention on Michelle Obama as the ‘face’ of her line of products she is marketing for a global audience.

In Michelle Obama’s autobiography there is an emphasis on the importance of women learning to use their own voices. Michelle experiences the uses of her voice and she shares stories about it. Yet the voice she uses is far from being noncontroversial. As a child, she is challenged by another girl because of her speech: “How come you talk like a white girl?” (40) – which she indeed does, her family intent on taking pride in the proper (white) way of speech, seeing it as a “way to transcend, get ourselves further” (40). It takes her get used to hearing her own voice in rooms dominated by white and mostly male others, but she strives to do so and by the time she becomes a lawyer she is “tri-lingual:” she speaks the patois of the South Side, the academic language of an Ivy League school, and a lawyer’s precise language (94). Eventually, she manages to succeed in articulating her needs as a working mom as well: “no matter how it panned out, I knew I’d at least done something good for myself speaking up about my needs. There was power, I felt, in just saying it out loud.” (202)

Much later, in her campaign speeches for her husband, she relies on her own story as an illustration of the principle that change is possible. She shares her own story in order to connect to people in the way Barack had talked about in the community meeting back in Chicago’s far South Side in the 1990s: “our stories connected us to one another and through those connections it was possible to harness discontent and convert it into something useful” (116). Similarly, her later talks to students stress her commitment to using one’s voice at the intersection of other issues like stereotypes and visibility. At the Elizabeth Garrett Anderson School for girls in England she projects her earlier self into the hopeful faces of colored girls around her:

"You had only to look around at the faces in the room to know that despite their strengths these girls would need to work hard to be seen. There were girls in hijab, girls for whom English was a second language, girls whose skin made up every shade of brown. I knew they would have to push back against the stereotypes that would get put on them, all the ways they would be defined before they’d had a chance to define themselves. They’d need to fight the invisibility that comes with being poor, female, and of color. They’d have to work to find their voices and not be diminished, to keep themselves from being beaten down." (318)

Projecting her own life trajectory for the girls, through this anecdote Michelle Obama maps out the girls’ future at the crossroads of education, finding a voice and gaining visibility against the work of biased clichés and stereotypes of the American gaze.

The voice and visibility she acquires in the above scenarios is referred to as soft power by her and her reviewers. She prefers soft power to direct confrontation in the text and her invention of roles play a part of that strategy. Peter Conrad describes her ‘soft power’ as a subtle mixture of domestic and public roles:

"Hillary Clinton antagonised housewives everywhere by refusing to stay at home and bake cookies; as First Lady, Michelle devoted herself to planting a vegetable garden in the White House grounds – an enterprise that looked harmlessly domestic, although this “miniature Eden” also provided her with an excuse for lecturing obese America about healthy eating." (Conrad)

In turn, St. Félix connects her soft power to the power of celebrity, as she is: “being awesomely at home wielding the soft power of celebrity” (St. Félix). Her soft power is neither traditional domestic power not political power per se: rather, it is the power to generate public attention and concern through her socially visible projects.

The process of change through the use of voice, new roles, and raising visibility described above appears to be similar to the notion of empowerment in classic Black Feminist texts. In Black Feminism, empowerment refers to an individual African American woman learning to speak for herself, also becoming one voice in a dialogue among people who have been silenced. In her Black Feminist Thought Patricia Hill Collins defines empowerment as an experience that “an individual black woman experiences when her consciousness about how she understands her everyday life changes” (x), which

"may stimulate her to embark on a path to personal freedom, even if it exists initially primarily in her own mind. If she is lucky enough to meet others who undergo similar journeys, she and they can change the world around them." (x)

Collins’ own individual voice as a critic provides a survey of Black female theorists’ thoughts on social injustice and empowerment, thus joining a dialogue and breaking the path for stories by others about change in their everyday lives. Similarly, Michelle Obama’s conclusion stresses the point that she told her own story of learning in order to make others follow her path:

"In sharing my story, I hope to help create space for other stories and other voices, to widen the pathway for who belongs and why. […] For every door that has been opened to me, I have tried to open my door to others." (421)

The subject position this kind of life writing determines is that of an African American female ‘speaking subject’ with a voice of her own. The book presents the process of how the voice emerges in the titles of its sections: a personal, a matrimonial, and a political voice coming into being supposedly one after another. However, logically what comes into being here it is ordered differently, the other way around. The speaking “I” has a political-communal voice, and a partner’s voice, but most importantly, it is an individual’s voice intent on change in the life of the individual for additional communal purposes against institutionalized forms of oppression (one form of activism in Collins, 204). This trajectory of the voice indicates that the subject position determined here is wider than initially thought: it is not only an African American female position but also that of the learned, reflective, professional woman intent on personal, social, and possibly political change.

4. Metaphors of ‘Becoming’

The text relies on two spatial metaphors which illustrate the process of becoming in a meaningful way: the garden and the White House old family dining room. Both the garden and the dining room appear as actual domestic spaces with wider metaphorical public connotations related to minority female role models and change as empowerment. The garden figures in the text as the First Lady’s actual garden and also as the “symbol” of her striving to perform an impactful job as a First Lady. To supplement the already existing decorative Rose Garden, Michelle Obama set out to start her garden on the South Lawn in 2009. The design consisted of raised beds of vegetables and herbs joined by paths, with border flowers. Groups of children came from local schools to help with planting, weeding, harvesting, and consuming. Through the years, the garden grew in size and was eventually equipped with benches and stone paths.

The general aim of the planting the garden was to raise the visibility of the need for healthy food for schoolchildren. The pretty image of a garden worked by schoolkids caught the public eye and so did the connected project of healthy food for kids in the form of healthy lunches, healthier selection of items in school cafeterias, less added sugar in food products aimed at child consumers. The garden was paraded as the source of fresh healthy produce, the transformative engine in which “seeds took root,” “plants produced” edible food from the dirt, as its published story American Grown already indicates (Michelle Obama 2012, 18). In a garden, relatively little investment can bring a big profit, provided the young plants are taken care of, are protected, watered. At the same time, there is also a measure of contingency at work in its life, as the weather may devastate any amount of careful tending.

The wider significance of the garden lies in the fact that it embodies growth, it stands for the project of change so important in Michelle Obama’s universe. In a garden the same events happen as in the case of personal change: taking root, producing (311), whist it needs to be tended carefully. For a garden, one has to plan, plant, care, watch, harvest, process – the full spectrum of growth has to be tackled. This cycle of growth needs an investment so that value is created. More specifically, The White House Gardens represent, as Martha MacDowell has argued in her recent book, the aspirations of American horticulture, which she sees as “a persistent metaphor for American culture” (McDowell 11) in general: Lincoln’s goats and the Kennedy’s roses lead the way to Obama’s vegetable patch.

In the case of Michelle Obama’s kitchen garden, the growth is both actual and communal, as not only plants grow but also people paying attention to them emerge. As Michelle commented on one of her initiatives “as with the garden, I was trying to grow something—, a network of advocates, a chorus of voices speaking up for their children and for their health,” (348) that is, not only plants but attention to them, too. Placing even beehives into the garden seems almost an overdoing of this metaphor for industry, diligence, and effort. Similarly, Barack Obama compared community organizing to “tending a garden” (Barack Obama 311), the ‘growth’ for the community being cohesion and common aims and voice. In this sense, garden work and life symbolize “diligence and faith” (336), as Michelle puts it, because of the commitment needed and the lurking contingencies all gardeners take for granted at the outset. The method needed for maintaining a garden makes Michelle’s old idea of effort and reward in a community context highly visible, both physically and metaphorically. This way the garden becomes a metaphor for Michelle Obama’s actual initiative and for her general method as well.

At this point it is necessary to mention that the image of the kitchen garden has been a recurring trope in writing by African American women. The creativity of African American women invested in tending the kitchen garden was described by Alice Walker in her widely known essay “In Search of Our Mothers’ Gardens.” Walker was searching for female literary roots, and after having found the work and grave of Zora Neale Hurston, she began to think why there were so few female literary ancestors to locate (Walker). In the essay she points out that literacy was not the main area of expressing creativity in the African American context, let alone among women. The creativity of African American mothers played out in different ways: in singing, in sewing, in cooking and last but not least in the kitchen garden they tended in their few spare moments (Walker), the luxuriant growth that brought food and renewal, rich with lush flowers.

So the kitchen garden on the South Lawn of the White House represents a space of feminine creativity also rooted in the African American experience. It is important that instead of yet another flower garden, the addition is an actual vegetable patch: working class, practical, functional, a lasting trace of minority presence in the space of the White House. No wonder Michelle Obama made every effort to preserve the garden after she left: as one of her last official actions, she set the garden in stone (Bottemiller Evich), had it fortified by stone structures so that the mark remains. The garden represents her legacy as First Lady.

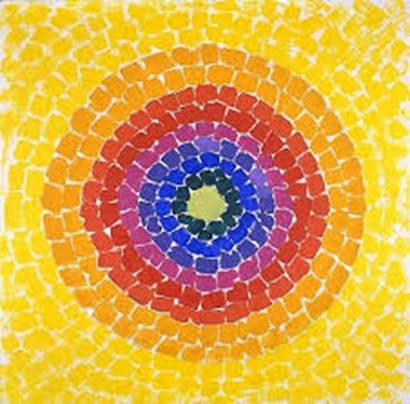

Another, perhaps less popular but equally spectacular metaphor of the process of ‘becoming’ in the text can be found in the redecorated small old family dining room of The White House. Originally, the small dining room was used for private events like work lunches, decorated in Neoclassical style, not open for visitors. The new design has a more Modernist optics, apart from changing the color of the walls from yellow to grey, the carpet and the curtains, the major addition to the room consisted in decorating it with Modern art by Robert Rauschenberg, Josef Albers and Anni Albers. The most significant addition was the piece Resurrection (1966, see below) by Washington Color School artist Alma Thomas, the first African American painter whose work is included in the White House permanent collection.

Commenting on the redecorations, Margaret Russell, editor-in-chief of Architectural Digest said that “[t]his is a terrific reflection of what the Obamas are doing in the White House. It is very respectful of the past yet embraces today,” The Washington Post reported. I would add that here again factual and metaphorical meanings of space are interposed on each other, as it happened in the case of the garden. Relating to ‘what the Obamas are doing in the White House’ both as a building and as the government, the redecorations are indeed illuminating. So much so that it is not only a constructive relation to the past that the redecorations reflect on both planes but also the willful inclusion of minority presence, an opening up of space for the public eye, all set up in a highly mannered and feminized form of action: interior decoration.

In Becoming feminine domestic spaces of the vegetable patch and the family dining room are opened up for public view and use. The opening up results in transforming these spaces from private to public ones with communal functions. The revision of the traditional use of these spaces involves the inclusion of the racial element as well.

5. Circulation, Consumption

The volume was contracted as part of a 65-million-dollar publishing deal with global circulation and publicity. Its positive international reception signals the fact that the Michelle Obama trademark has become an international mold easily embraceable by a wider audience than its original generic limitations would indicate. One of the most interesting questions for me is why this is so?

As shown above, the old slave narratives were written for a white audience with the aim of persuading readers to sympathize with the case of the African American storyteller. Not surprisingly, Michelle Obama’s autobiography has an appeal for white readers as well. It is a careful representation of anecdotes that maintain the subtle balance of documentation and case argued, criticizing US party politics and racial politics just mildly, foregrounding the positive self-fashioning process of ‘becoming.’ Erin Auby Kaplan calls this strategy of handling racial issues a ‘strategic shutting down’ the discussion of racism in America (Kaplan), a sad choice by a prominent African American who could have chosen to be truly emphatic to African Americans by “broaden[ing] the national narrative of exclusion from a story of black striving and overcoming to a story of black discontent” (Ibid). For Kaplan, this “follows the rules of assimilation.” Surely, she means assimilation in the vein of Booker T. Washington, Teddy Roosevelt’s one-time guest to the Old Family dining room.

Afua Hirsch reflects on the same scenario in a much more positive light. After pointing out that the American Dream context fits no African American story, not even Michelle Obama’s, because of the history of African Americans in the US, she diagnoses the fact that “most of Obama’s narrative on race, however, comes courtesy not of her own perspective, but that of the many commentators who weaponised her blackness against her,” a large part of which she chooses not to tell (Hirsch). Hirsch sees Obama’s gesture of emphasizing an idyllic childhood and upward social mobility instead of communal suffering and injustice in the South Side and at Ivy League institutions as a dignified tone reflecting the doctrine ‘When they go low, we go high.’ For Hirsch, the gesture of not telling forms part of Michelle Obama’s appeal.

One can also consider this strategy of talking about race in the light of the ‘effort-reward for the community’ continuum discussed so far. Considering Barack Obama’s basic conviction Michelle shares early on already that “our stories connected us to one another and through those connections it was possible to harness discontent and convert it into something useful” (116) in the light of Kaplan’s and Hirsch’s comments, I believe Michelle Obama does rely on the strategy of choosing not to tell much about humiliating race relations. The reason for this most probably is that she chooses to do something about them. In the framework of social mobility for the community, black discontent becomes the motivation behind pragmatic action aimed at restructuring and reinterpreting traditional US race relations and roles. For instance, by selling more books in 2018 than Fox ex-host author Bill O’Reilly who had infamously said back in 2007: “I don’t want to go on a lynching party against Michelle Obama unless there is evidence” (quoted in Hirsch).

This agenda reads like trying to initiate way out of the classic twentieth century opposition initiated by Booker T. Washington and W. E. B. DuBois. On the one hand, Booker T. Washington’s Atlanta compromise for assimilation did not include the option of renegotiating US race relations and shifting the status quo, neither did it stress the need for college education or for a voice whilst it insisted on racial compromise and industrial training (Washington). On the other hand, W. E. B. DuBois’s strategy for racial uplift involved the need for college education for the talented tenth, the belief for political power from top to bottom, the need for exceptional men (Du Bois). From the perspective of the Obamas’ emphasis on ‘change,’ neither resurrection nor exceptional (wo)men need wait. In Washington’s post-slavery world, resurrection was to happen in the far away future, not in the present while for the Obamas resurrection has already happened in the near past of the present perfect. That is why ‘Resurrection’ is (was) also hanging on the wall of the White House as part of a public display, where the Obamas have arrived as the result of their education and grassroots activism.

With the book’s work ethic and its ‘When they go low, we go high’ dignified doctrine the special US brand “Michelle Obama” has been invented. The brand has also been sold in the multimillion dollar business deal and the book is part of the marketing of the Michelle Obama brand for a global audience. The international stops of the book tour and the instant translations of the volume indicate the global scale of the marketing process. The brand sold is that of the intelligent, affluent, self-assured, professional, glamorous, democratic ex-political figure whose image may represent a moment of relief in the context of global political populism.

Indeed, I believe we are witnessing the birth of a book cycle here. After Michelle Obama’s first book on her First Lady’s garden American Grown, Becoming comes as her second volume, and if the principle for telling one’s story laid out in the book holds and the brand supporting this image is to be kept up, other books will follow. Writing books in print or thorough an internet platform of some sort like a blog or a homepage would be a natural way for keeping up the visibility of the Michelle Obama brand. Becoming may be even rewritten like Frederick Douglass’ Narrative that was rewritten three times, each time with a new and more political speaking subject (Stauffer, 214 and Stepto 2009b, viii). With Michelle’s captivating words resonating, I cannot wait to read and discuss them in due course.

Conclusion: Seeds of Change

Michelle Obama’s autobiography relies heavily on the discourses of the African American autobiographical tradition and female writing. Her text explores the key theme of conversion familiar from nineteenth-century slave narratives that reemerges with an added pragmatic aspect to it and explores how change can be present in the life of an individual who happens to be African American and female – in the face of standard expectations of social conformity and reproduction. In this sense, Obama’s stress on ‘change’ in its multiple senses is a way to convert a traditional feeling of racial discontent. The feminine aspect of conversion, feminine empowerment represents the second key issue of the text, illustrating the power of stories and of making up stories in a hostile social context as a form of activism. (This aspect of the text is to be explicated in further detail in a companion article soon.) By combining pragmatism with a feminine perspective, Michelle Obama is building a popular and lucrative cultural brand that attempts to provoke change in social life by showcasing it in literature.

Works Cited

- Andrews, William L. 1989. “Narrating Slavery” In Maryemma Graham et. al., eds. Teaching African American Literature: Theory and Practice. New York: Routledge. 12-30.

- Bottemiller Evich, Helena. 2016. “Michelle Obama Sets her Garden in Stone” Politico May 10, 2016. https://www.politico.com/story/2016/10/michelle-obama-garden-changes-white-house-229204 Access: May 10, 2019

- Carby, Hazel B. 1989. “The Canon: Civil War and Reconstruction” Michigan Quarterly Review 28: 35-43.

- Cartner-Morley, Jess. 2018. “Amazing Grace: Michelle Obama and the second coming of a style icon.” The Guardian Dec. 4, 2018. https://www.theguardian.com/fashion/2018/dec/04/amazing-grace-michelle-obama-and-the-second-coming-of-a-style-icon Access: March 27, 2019

- Chotiner, Isaac. 2019. “Valerie Jarrett Looks Back on the Obama White House” The New Yorker April 1, 2019. https://www.newyorker.com/news/q-and-a/valerie-jarrett-looks-back-on-the-obama-white-house Access: April 3, 2019

- Collins, Patricia Hill. 2000. Black Feminist Thought: Knowledge, Consciousness, and the Politics of Empowerment. NY: Routledge.

- Conrad, Peter. 2018. “Becoming by Michelle Obama – review.” The Guardian Nov 18, 2018. https://www.theguardian.com/books/2018/nov/18/becoming-by-michelle-obama-book-review-peter-conrad Access: March 27, 2019

- Davidson Sorkin, Amy. 2018. “Michelle Obama and Politics: A (Sort of) Love Story.” The New Yorker Dec. 27, 2018. https://www.newyorker.com/news/daily-comment/michelle-obama-and-politics-a-sort-of-love-story Access: March 27, 2019

- Du Bois, W. E. B. 1903. “The Talented Tenth” https://teachingamericanhistory.org/library/document/the-talented-tenth/ Access: May 20, 2019

- Fisch, Audrey, ed. 2007. The Cambridge Companion to the African American Slave Narrative. Cambridge: CUP.

- Gould, Philip. 2007. “The Rise of the Slave Narrative” In Audrey Fisch, ed. The Cambridge Companion to the African American Slave Narrative. Cambridge: CUP. 11-27.

- Graham, Maryemma, Sharon Pineault-Burke and Mariana White Davies, eds. 1989. Teaching African American Literature: Theory and Practice. New York: Routledge.

- Hirsch, Afua. 2018. “Becoming by Michelle Obama review: race, women, and the ugly side of politics.” The Guardian Nov. 14, 2014 Access: Nov. 15, 2018.

- Kaplan, Erin Aubry. 2019. “Michelle Obama’s Rules for Assimilation” The New York Times Feb 24, 2019. https://www.nytimes.com/2019/02/24/opinion/michelle-obama-becoming.html Access: March 28, 2019

- Koncius, Juara and Krissah Thompson. 2015. “Michelle Obama redecorated a White House room – and it’s much more modern.” The Washington Post. Feb. 10, 2015. https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/arts-and-entertainment/wp/2015/02/10/michelle-obama-redecorated-a-room-in-the-white-house-hint-its-super-modern/?utm_term=.53e617534138 Access: March 29, 2019

- Lamore, Eric D., 2016. “Introduction: African American Autobiography in ‘The Age of Obama’” In Lamore, Eric D., ed. Reading African American Autobiography: Twenty-First-Century Contexts and Criticism. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press. 3-18.

- McDowell, Martha. 2016. All the Presidents’ Gardens: Madison’s Cabbages to Kennedy’s Roses – How the White House Grounds Have Grown with America. Portland: Timber Press, 2016.

- Morrison, Toni. 1995. “The Site of Memory” Inventing the Truth: The Art and Craft of Memoir, 2d ed. Ed. William Zinsser. Boston; New York: Houghton Mifflin. 83-102. Web. Jan 28, 2017. https://www.ru.ac.za/media/rhodesuniversity/content/english/documents/Morrison_Site-of-Memory.pdf

- Obama, Barack. 2004. Dreams from my Father: A Story of Race and Inheritance. New York: Three Rivers Press, (1995).

- Obama, Michelle. 2018. Becoming. New York: Crown Publishing.

- ——. 2012. American Grown: The Story of the White House Kitchen Garden and Gardens Across America. New York: Crown Publishing.

- Rushdy, Ashraf H. A. 1999. Neo-slave Narratives: Studies in the Social Logic of a Literary Form. Oxford: OUP.

- Stauffer, John. 2007. “Frederick Douglass’s Self-fashioning and the making of a Representative American man.” In Audrey Fisch, ed. The Cambridge Companion to the African American Slave Narrative. Cambridge: CUP, 2007. 201-217.

- Stepto, Robert B. 2010. A Home Elsewhere: Reading African American Classics in the Age of Obama. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press.

- ——. 2009. “Introduction: Frederick Douglass Writes His Story” In Frederick Douglass. The Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave. Cambridge: Harvard UP. vii-xxviii.

- St. Félix, Doreeen. 2019. “Michelle Obama’s New Reign of Soft Power” The New Yorker Dec. 6, 2018. https://www.newyorker.com/books/page-turner/michelle-obamas-new-reign-of-soft-power Access: March 27, 2019

- Walker, Alice. 2002. “In Search of Our Mothers’ Gardens: The Creativity of Black Women in the South” Ms. Magazine 12(2002 Spring):2. http://www.msmagazine.com/spring2002/fromtheissue.asp Access: Sep. 10, 2009

- Washington, Booker T. 1895. “Atlanta Compromise Address 1895” History Matters. http://historymatters.gmu.edu/d/39/ Access: May 20, 2019

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.