“I am not erudite enough to be interdisciplinary but I can break rules.” (Spivak)

There is no such thing as wrong screening room and that’s a good thing, too.

(After Stanley Fish, who later attacked Alan Sokal’s intellectual trap on interdisciplinarity in humanities)

In Don DeLillo’s Americana, David Bell, “the child of Godard and Coca-Cola,” (DeLillo, 269) a young TV network executive, takes his 16mm Canon Scoopic camera and decides to explore the very heart of America. As he starts shooting, people in front of the lens start to open up, and David succeeds in revealing something innermost, something hidden, a kernel that for him defines America. This lies behind the power of the image of America – but curiously, the film stock will never make it to the screen.

[source:

http://www.canon.com/camera-museum/camera/cine/data/1970_ds8.html]

[source:

http://www.canon.com/camera-museum/camera/cine/data/1970_ds8.html]

David Bell’s camera nonetheless captured the image that may be comprehended as the “cultural idiom” expressed through imagery, more precisely, through the cinema. This way, the cinema becomes a kind of screen for the subject to access cultural definitions, cultural information, more precisely, it becomes an interface.

Today the interfaces that help retrieve and use information, above all cultural information, are predominantly visual: photography, cinema, VCR, DVD, and the computer, which has come to dominate the visual landscape in this sense, acting as the par excellence interface among interfaces. Lev Manovich defines the technological apparati that enable the user (who is no longer a mere spectator or an observer, but an interactive agent engaged not only in the production of meaning but of the work of art as such) to access and work with cultural information as cultural interfaces (Manovich, 68). Although Manovich insists on the primacy of the computer and the human-computer interface acting as the example of cultural interface, arguing for the active use of imagery and real-time response, I wish to broaden the scope, since the older cultural forms, such as the cinema, did not only contribute to the development of such interfaces, as he claims, but also they have become such cultural interfaces as more and more techniques have been feeding back into their mechanism. Just to mention one example: it is true that filmic techniques had enormous influence on the form and content of computer games, but it is equally true that specific computer game formulas and visual techniques revolutionized the cinema in turn. In other words, computer-based data processing in terms of cultural information has come really close to the way the cinema is used as such an interface today.

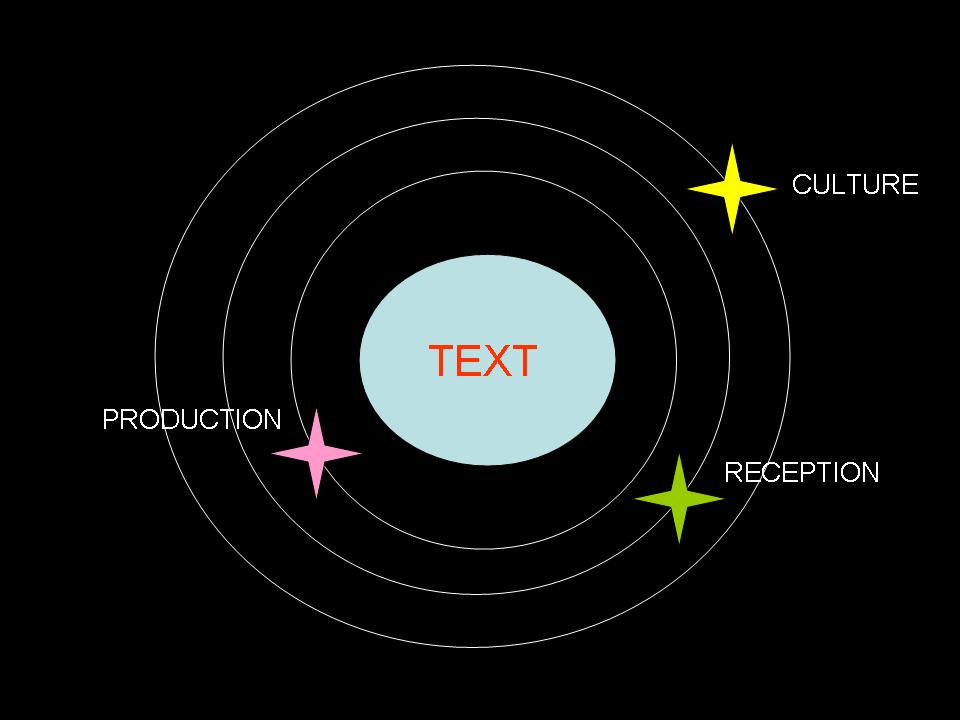

To pursue this idea further, let me turn to perhaps the most “delicious” definition of the cinema by Rick Altman. Contrary to the usual way of defining cinema as a text, utilized by traditional film studies, where the strata playing roles in the production of meaning circulate without any apparent interaction – culture thus floats without influencing the reception, reception does not have any effect on production, and production is seen as detached from the produced film text - Altman understands cinema as an event.

[image based on Altman's diagram, Altman, 2]

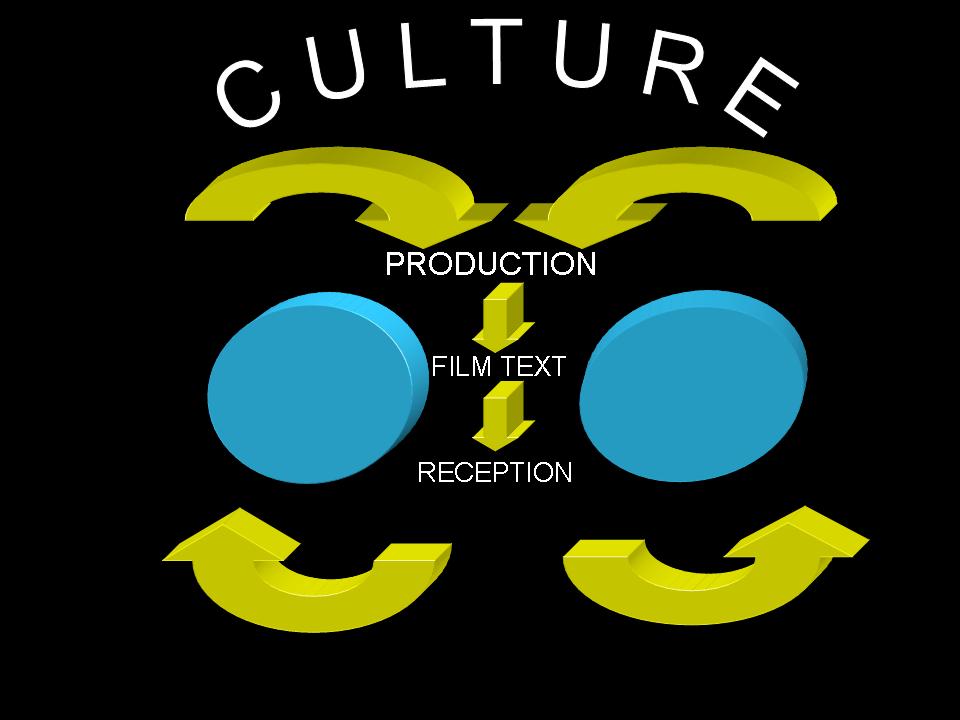

The consequences of this shift are liberating. First of all, cinema becomes an interactive event, not a one-way information retrieving act, since the separation of the dimension of cinematic meaning production is in Altman’s view channeled into an endless process of interaction. Second, the spectator is not simply “pulled” into the event, but partakes of it, actively engaged with the cultural information available via the cultural interface of the screen, becoming a user of information instead of a passive receptacle. This also means that the user produces responses triggered by the cultural information that feeds back into the circulation. This endless circle of production and perception finds its visual model in Altman (3) in the form of the doughnut:

![]()

[image based on Altman's diagram, Altman, 3]

[image based on Altman's diagram, Altman, 3]

The context in which the doughnut exists is culture, of course, and one may proceed in the model from the top, i.e. the site of production through the central hole (the individual film) towards the other side, the site of reception, broadening out into the context of culture itself, and – on the same surface, like in a Moebius strip – the interaction reaches the point where it began. What this model calls attention to is that no cultural product accessed via a cultural interface can be seen as a one-way model, occasionally transmitting cultural information without being reacted to immediately in an interactive manner by the users of that information with their separate and particular cultural context and situated knowledge.

Let us see how this works. Our example here is Jay and Silent Bob Strike Back (2001) directed by Kevin Smith [trailer | features], since this funny movie quite explicitly sheds light on the way the doughnut model operates. The Lawrence-Hardy figures of Jay and Silent Bob are first (in the previous films of Smith) models for comic strips. As the popularity of the comics rises, Hollywood soon tries to take financial advantage of the phenomenon, and plans to make a movie based on the Jay and Silent Bob stories. However, the two protagonists learn that on the Internet there already is a huge debate whether the stories should be turned into film or they are just trash and not worth a dime. Still in the production phase, Jay and Silent Bob traverse the US to get to Hollywood and take over the production of the film about the figures they are the primary models of. They arrive at Miramax studio, which is actually the studio producing the very film(s) in which they appear, and try to get involved in the making of their own movie.

So far it should be clear that the production is, paradoxically enough, already preceded by the reception, which thus has an influence on the film text that is planned to reach the audience. Moreover, when Jay and Silent Bob hit the studio (almost literally taking it by storm), a very elaborate and eloquent intertextual and interactive cultural game begins, as they meet their own cameos (played by James van der Beek from the hit teen TV series Dawson’s Creek and Jason Biggs, star of the American Pie films) and engage in a fight with Mark Hamill, alias Luke Skywalker, but before that they occasionally meet a nun played by Carrie Fisher, a.k.a. Princess Leia... Clearly, the title of the film, then, i.e. Jay and Silent Bob Strike Back is already playing on the cultural knowledge of the spectator-user, and invites him/her to engage in a complex intertextual game that can be only effective and amusing if the cultural interface is activated by the user.

What happens to the cultural idiom then? If the cultural idiom is transmitted through a cultural interface as, par excellence, an image, then it obviously has to go through this interactive model, reproduced – today primarily – digitally, electronically and visually. Interestingly and importantly, this reproduction involves the user as a co-author, which is an obvious change of the situation described by Walter Benjamin in his seminal essay “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction.” It is at this juncture where the study of the US and the Americas becomes intriguing especially from our Szeged point-of-view, since our engagement with cultural information from and about America is predominantly visual and retrieved via cultural interfaces.

Walter Benjamin prefigured the potential of the cinematic medium when he stated that “[film as] immediate reality has become an orchid in the land of technology” (Benjamin, 235). This “orchid” has been the most popular among other species of technological organisms insofar, apart from TV and Internet. Andr� Glucksman (who was often quoted by Susan Sontag) was the first to claim publicly that “wars are won or lost on TV” in our world of mediated reality and pictorial turns, of images and image-makers. W.J.T. Mitchell called this current obsession the tyranny of the visual. Paul Virilio, in turn, remarked that in the age of electronic reproduction when success depends ultimately on “the conquest of image,” it is viewing and screening that replaces real existence. “Rewind, Play and Fast Forward,” Virilio notes, have replaced our “Past, Present and Future.” In an interview Norman Mailer gave to The American Conservative in December 2002, after the interviewer stressed the cinematic facet of the amateur videos that filmed the 9/11 event in NYC, the writer responded: “ […] we were watching the same action movie we had been looking at for years. That may be at the core of the immense impact 9/11 had on America. Our movies came off the screen and chased us down the canyons of the city” (Chan, 2003). These examples recount the power of the image (and the technological apparatus behind it) in building and contesting a given cultural reality.

The study of the U.S. has greatly employed―as if under the aegis of Gene Wise’s “ritual rhetoric of newness”―current technologies, as “immediate realities” to work in favor of a more internationalized study of America. The multimedia world of the international CNN-effects, of America on-line, the discursive world of techno-fundamentalism and electronic ‘colonization’ have not only complemented the luxury world of disciplinary anachronisms―that seem to function more and more as a kind of theme park (or rather ironically as South Park) within the ever expanding field of American Studies of the third millenium―but opened new critical [G]ates and ‘[W]indows’ to the world as yet another (Macintosh) ‘[A]pple’ from the tree of cultural knowledge.

[source: http://www.southparkstudios.com/downloads/images ]

American Studies through film, as American Studies in general, are saturated with building and contesting theories and methods regarding the field. The film as immediate reality is one of the best playgrounds for these contests. As Sol Cohen remarks, contemporary film studies depict a “boundless, undisciplined discipline.” By deconstructing the epistemological boundary between fiction and non-fiction, a fiction film becomes its own documentary, Sam Girgus claims, because the film is the cultural witness of the age when it was produced. Think of the more or less humorous example in Galaxy Quest (1999, directed by Dean Parisot) where a group of aliens take for granted the (mocked) Star Trek film series as a real, historical documentary of American culture.

[source: http://www.allmoviephoto.com/photo/1999_Galaxy_Quest_photo.html ]

They kidnap the scared actors―themselves ironic remakes of the Star Trek real actors, who are doing promotional work to improve movie sales―in order to save their extraterrestrial civilization on the basis of an American filmic experience thought real and thus useful by the alien 'others'. The paradox is that the visual innuendo of the aliens proves useful in their war against their enemies, and thus establishes the ‘watched’ film as the culturally equivalent genre for ‘doing history.’

[source: http://www.allmoviephoto.com/photo/1999_Galaxy_Quest_photo.html ]

Under the guiding tenet of films being at the same time their own documentaries, fiction films about America have become, outside the country, and even inside it, cultural recordings of a given time and place. The American cinema, in this context, is a multiple cultural space that represents a special type of interpretation; it exposes multiple systems and views of American experience and meaning production to another interpretive community. Film is a medium through which a culture can present itself to other cultures while keeping a variable mirror to itself. American film industry, with special regard to Hollywood, is one of the best image-makers of the country. It is the universality of image and film language that plays the role of common denominator in presenting, translating, commenting, understanding and contesting a culture. The American film is the medium that presents the area studies of the United States in the form of the cultural contour. It is an interpretative context that presents to the world multiple iconic movements of what America seems to be. From center(s) or margin(s), whatever angle the issue was joined from moviemakers to viewers, America remained “a point of reference.” (Kroes, 75) Perhaps more than any commodified form of American culture, the American film has heavily been, especially in the past decades, subject to intense international commentary and gained special emphasis in the academic curricula about the study of the United States.

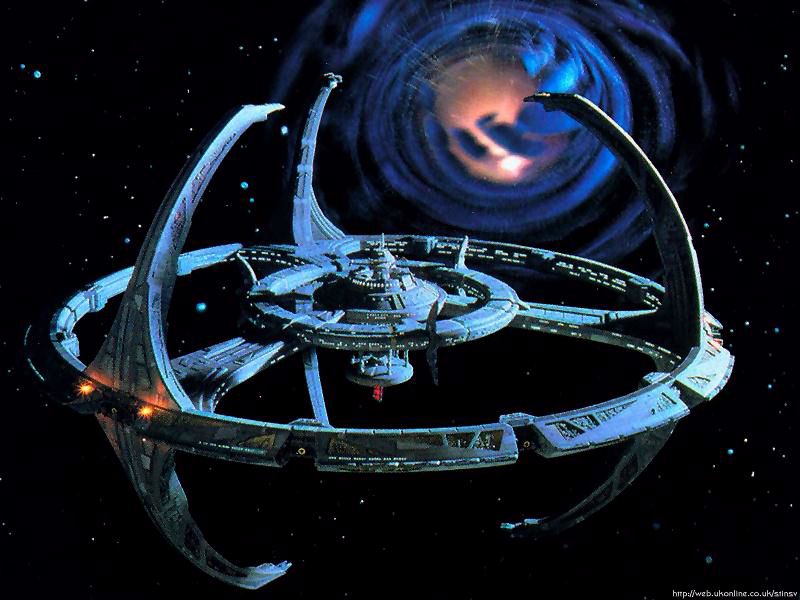

On the level of U.S. symposia, similar to a permanently increasing number of American and non-American scholars (Paul Lauter, Alice Kessler Harris, Emory Elliott and many others) Jane C. Desmond and Virginia R. Domínguez argued in 1996 in “Resituating American Studies in a Critical Internationalism” for a concerted effort in American Studies to evolve toward a more intensified internationalization of the study of United States by more fully involving non-U.S. scholars in the production of cultural texts about the U.S. in a creative critical interface between domestic and international perspectives. More recently, John Carlos Rowe advocated a “new internationalism that will take seriously the different social, political, and educational purposes American Studies serves in its different situations around the globe” (Rowe, 27, 31) and called for a post-nationalist thinking in the study the United States. Donald E. Pease, Robyn Wiegman and the New Americanists urge for a permanent dialogism between the multiple “futures” of the discipline, ranging from the “comparatist” to “posthegemonic,” “differentialist” and “counterhegemonic” studies (Pease and Wiegman, 1-42). On the level of non-U.S. based American Studies conference in 2003, at the opening speeches of the American Study Days in Szeged, Hungary, Bálint Rozsnyai the chair of the American Studies Department of Szeged University and Jonathan Veitch, dean of Eugene Lang College, New York stressed the imminent importance of multimedia employed interdisciplinary teaching, study, research and understanding of the U.S. in the context of New American studies. Among the current modes of U.S. studies in the global context, film as a paradigm of critical internationalism has taken its most pragmatic role at our Institute of English and American Studies, too. The American film has become in the past years at the Department of American Studies (that this year celebrates it 20th anniversary) not as much as an option but rather an imperative. The American film and the American visual culture, here and now, are viable analytical spaces of cultural and intercultural understanding. Our Institute and especially the Department of American Studies host an increasing number of optional courses on American film, film adaptation, film semiotics, and a survey course on film theory. As a result, a mounting number of major papers and MA papers are currently written in the field of film studies and visual culture. The study of America through film, in this context, is at its best when it serves―as Siegfied Kracauer, Erwin Panofsky or Stanley Cavell have shown―an “external reality.” The America of outside America is similar to the space bases of the Deep Space 9, Voyager, Babylon 5 that work as cultural intertexts that promote the study of a culture from outside the entity that is considered to be The Country.

[sources:

http://www2.warnerbros.com/babylon5/imagecorridor.html;

http://www.xs4all.nl/~dassel/wall/ultimate.jpg;

http://www.startrek.com/startrek/view/library/episodes/VOY/index.html ]

In tandem with this internationalizing function the logo of the

Department of American

Studies in Szeged depicts an astronaut

signifying the non-US based scholar in its quest for understanding US from

outside its geographical limits. (Cf. also Bálint Rozsnyai’s response to the

issue of Internationalizing American Studies at

http://crossroads.georgetown.edu/interroads/rozsnyai.html.)

signifying the non-US based scholar in its quest for understanding US from

outside its geographical limits. (Cf. also Bálint Rozsnyai’s response to the

issue of Internationalizing American Studies at

http://crossroads.georgetown.edu/interroads/rozsnyai.html.)

Among the new technologies employed in the study of American culture in the

age of electronic reproduction the Internet with all its .org, .net, .gov,

.com sites has taken its pragmatic role. Internet provides dynamically

interactive syllabi such as the American Studies Crossroads project

![]() ,

while American films (TV, video, CD-ROM/DVD) usually function as primary

texts (similar in function to the literary texts) in the curricula. The

Internet and film introduce, as Alan B. Howard argued, three dimensions to

the enterprise of the study of America (Howard 1999). First of all, these

new databases are more democratic tools for interrogating cultural ‘dogmas,’

canonized or marginalized paradigms through URLs, listservs, blogs,

discussion rooms and lists, mailing lists, etc. These allow the

incorporation of enormous quantities of information from all over the globe

and permit much subtler kinds of analysis from the polyphonic hyperspace.

This might be one very popular approach in the so-called post-hegemonic

global American studies. Secondly, the multimedia as ‘technicalia,’ permit

the organic inclusion and a more widespread academic use of ‘unconventional

histories’ of the non-canonized cultural pradigms that have been treated as

“naive or amateur” images, objects, sounds, events, etc. within the

institutionalized frame of the American Studies (Cf. Roy Rozenzweig’s CD ROM

Who Built America?

http://www.ashp.cuny.edu/WBAcd-roms.html and

http://www.ashp.cuny.edu/WIP1.html This project started in the 1990s as

a collection of memoirs, family photos and oral interviews and is now one of

the canonized, frequently referred hypertext databases in U.S. studies.)

Because of its interactive character multimedia enhances the existence of a

live interface, conceived as a “technologically mediated collaborative work”

(Howard 1999) between academics, between teachers and students, among

students, between academics and non-academics. This is the third and perhaps

most complex dimension in the study of American in the current age. In other

words, the employment of new technologies inaugurates a multifold modeling

for New Americanists by presenting “multiple perspective solutions to single

problems usually posed within the walls of a classroom” or conference

building. According to Alan B. Howard, the new technologies adapted to the

study of the U.S. tend to “subvert existing modes of thought” and “the

social and institutional structures that support them.” At the same time

these encourage “the proliferation of competing organizations” and schools,

and enhance the existence of various kinds of cultural texts that work

outside “traditional and established centers of authority” whatever they are

in given regional contexts. This process is an open-ended project―with all

its advantages and disadvantages―because, as Howard further states, it

allows “almost anyone to do American Studies with the authority the

technology itself confers, and to do it without the traditional internal and

external markers of legitimacy and reliability.” The ‘power’ points these

new technologies present within American Studies are the question of the

boundaries of the traditional discipline, the questionable notion of

expertise, and professional arenas capable of hosting and producing

“distinctive American Studies ventures” (Howard, 1999).

,

while American films (TV, video, CD-ROM/DVD) usually function as primary

texts (similar in function to the literary texts) in the curricula. The

Internet and film introduce, as Alan B. Howard argued, three dimensions to

the enterprise of the study of America (Howard 1999). First of all, these

new databases are more democratic tools for interrogating cultural ‘dogmas,’

canonized or marginalized paradigms through URLs, listservs, blogs,

discussion rooms and lists, mailing lists, etc. These allow the

incorporation of enormous quantities of information from all over the globe

and permit much subtler kinds of analysis from the polyphonic hyperspace.

This might be one very popular approach in the so-called post-hegemonic

global American studies. Secondly, the multimedia as ‘technicalia,’ permit

the organic inclusion and a more widespread academic use of ‘unconventional

histories’ of the non-canonized cultural pradigms that have been treated as

“naive or amateur” images, objects, sounds, events, etc. within the

institutionalized frame of the American Studies (Cf. Roy Rozenzweig’s CD ROM

Who Built America?

http://www.ashp.cuny.edu/WBAcd-roms.html and

http://www.ashp.cuny.edu/WIP1.html This project started in the 1990s as

a collection of memoirs, family photos and oral interviews and is now one of

the canonized, frequently referred hypertext databases in U.S. studies.)

Because of its interactive character multimedia enhances the existence of a

live interface, conceived as a “technologically mediated collaborative work”

(Howard 1999) between academics, between teachers and students, among

students, between academics and non-academics. This is the third and perhaps

most complex dimension in the study of American in the current age. In other

words, the employment of new technologies inaugurates a multifold modeling

for New Americanists by presenting “multiple perspective solutions to single

problems usually posed within the walls of a classroom” or conference

building. According to Alan B. Howard, the new technologies adapted to the

study of the U.S. tend to “subvert existing modes of thought” and “the

social and institutional structures that support them.” At the same time

these encourage “the proliferation of competing organizations” and schools,

and enhance the existence of various kinds of cultural texts that work

outside “traditional and established centers of authority” whatever they are

in given regional contexts. This process is an open-ended project―with all

its advantages and disadvantages―because, as Howard further states, it

allows “almost anyone to do American Studies with the authority the

technology itself confers, and to do it without the traditional internal and

external markers of legitimacy and reliability.” The ‘power’ points these

new technologies present within American Studies are the question of the

boundaries of the traditional discipline, the questionable notion of

expertise, and professional arenas capable of hosting and producing

“distinctive American Studies ventures” (Howard, 1999).

American Studies is today, more than ever, a dynamic process of cultural and technological dissemination that has long left the building of the Humanities and does not even think of asking, as the Donkey in Shrek: “are we there yet?” We, as multiple users of the curricular and extracurricular multimedia society should be more aware of the fact that the most important factors behind the technological apparatus and, at the same time, the most underutilized resource in any university, especially in the context of our regional New American Studies in the digital age, are the students themselves. In the light of W. Benjamin’s idea expressed above in this e-text, it seems that it is these electronically socialized students who are our most “immediate reality” in the age of electronic reproduction. Students are surfing with complex purposes among our distinctive regional American Studies venture(s), and they are primarily encouraged, as regional new Americanists, to inhabit the digital microcosm of the present Americana webpage. Together with the department staff (that provides courses, publications, academic performance, etc. inside or outside the university), our students can help building our department’s image, because they are part of the critical interface our department, institute and university present on an international, interdisciplinary terrain. Our students bring their technologized knowledge when practicing their craft inside but mostly “outside university” (Howard 1999) in a “transnational and translational” (Bhabha) world of intercultural exchanges dominated by images and representations.

Works Cited

Altman, Rick. (1992) "General Introduction: Cinema as Event," in Rick Altman, ed. (1992) Sound Theory/Sound Practice. New York: Routledge., 1-14.

Benjamin, Walter. (1973) Illuminations. London: Fontana/Collins.

Brown, James. (2002) “Review of Sam Girgus’s America on film: Modernism, Documentary and a Changing of America”. Retrieved from http://www.latrobe.edu.au/screeningthepast/reviews/rev_16/JBbr16a.html Access: 2004 November 16.

Cohen, Sol “An Innocent Eye: The “Pictorial Turn”, Film Studies…” Available: http://www.historycooperative.org/journals/heq/43.2/cohen.html Access: 2005. April 22.

DeLillo, Don. (1990) Americana. London: Penguin.

Desmond, Jane C. and Domínguez, Virginia R. (1996) “Resituating American Studies in a Critical Internationalism”, American Quarterly 48:3 (1996), 475-490.

Evans, Chan. (2003) “War and Images: 9/11/01, Susan Sontag, Jean Baudrillard, and Paul Virilio.” Retrived from http://www.filmint.nu/netonly/eng/warandimages.htm Access: 2004. November 24.

Girgus, Sam (2002) America on film: Modernism, Documentary and a Changing of America. Cambridge: Cambridge U P.

Howard, Alan B. (1999) “American Studies and the New Technologies.” Retrieved from http://www.xroads.virginia.edu/~AS@UVA/SAAS/main.html Access: 2004. June 9.

Kroes, Rob (1996) If You’ve Seen One, You’ve Seen the Mall. Urbana and Chicago: U of Illinois P.

Stewart, Kathleen (1996) A Space on the Side of the Road. Cultural Poetics in an “Other” America. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Pease, Donald E. and Wiegman, Robin, eds. (2002) The Futures of American Studies. Duke UP, Durham.

Rowe, John Carlos, ed. (2000) “Post-Nationalism, Globalism, and the New American Studies.” In Post-Nationalist American Studies, ed. J.C. Rowe. Berkeley and Los Angeles: U of California P., 32-39.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 2.5 License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 2.5 License.

Copyright (c) 2005 Réka M. Cristian, Zoltán Dragon

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.