1. Postcolonial Theories and the Early 1990s’ Disney Animations: Aladdin, The Lion King and Pocahontas

The aim of this essay is to analyze three major animated films of Walt Disney Pictures – namely, Aladdin (1992), The Lion King (1994) and Pocahontas (1995) – produced in the first half of the 1990s. I will exemplify with these three films the working pattern of postcolonial theory within the dominant American story-telling in the political context of the first Gulf War. I will provide a short summary on the related postcolonial terms and theory together with relevant film theories since this paper is a cross-section of postcolonial and film studies. Postcolonial focus will be on (1) the basic dialogue of culture and nature in and among the discourse of the films; (2) the description of three synthesizing characters and their Hegelian relation to one another. The aim is also to highlight the fact that the basic dialogues of characters and music through the conscious sequencing of the animated movies constitute nothing more than a retold version of the grand narratives of the American nation.

The recurring method of investigation in the present paper is the Hegelian dialectics (Hegel 647-692). The triangle of thesis-antithesis-synthesis can be found in and among the three films. Moving in a chronological order, Aladdin bears the thesis of culture; The Lion King is the antithesis of Aladdin, as it entertains the idea of nature; in the story of Pocahontas nature and culture are brought together and thus the synthesis is formed. Within each of the films there can be found a character who resolves the tension between the good and the evil characters. I call this figure a “synthesizing character” because without him/her/it the dichotomy between the opposing sides would never be resolved. The three synthesizing characters’ relation to one another implies the same dialectical method. Film music as traits of characters also fits into the framework of Hegelian dialectics.

The present analysis works on the fields of postcolonial and film studies, therefore the most important secondary sources are from these fields. Edward Said’s Orientalism is an often cited work in this paper. He claims that Orientalism is a Western style of domination and restructuring of the Orient (Said 873), which idea is precisely typical to Disney animations. The American interpretation of distinct cultures can be best understood with the help of Said’s article. Another book proved to be useful to me on the similar topic. It is E. Ann Kaplan’s Looking for the Other, which deals with postcolonial issues in the framework of films. Since this paper is also a cross-section of filmic and postcolonial studies, this book helped me a lot in pointing out filmic phenomena that carry postcolonial relevance. Mouse Morality, written by Annalee R. Ward, offers full interpretations of Disney animated films. The author analyzes the movies from a moral perspective, which has not always served my interest. However, several notable remarks are involved in her argumentation, and for this reason, I found it reasonable to cite them. Last but not least, I would emphasize the merits of Alan Nadel’s article “A Whole New (Disney) World Order: Aladdin, Atomic Power, and the Muslim Middle East.” Nadel offers several reasons and clues on the tight relationship of the picture Aladdin and the actual political power relation between the United States and the Middle East. His article was of great help to me when discussing Genie’s character as well.

The key concept of postcolonialism, according to Bill Aschcroft, is an uncentred pluralist point of view of experience, that is, the intermingling of the center and the marginal (Aschcroft 11). Under the terms ‘center’ he means the “privileging norm,” the one that is the denial of the value of the peripheral (3). Aschcroft claims that imperial expansion resulted in the destabilized, pluralist point-of-view in which the acknowledgement of central values exclusively is not possible. One cannot talk about Aladdin only referring to the American values inserted in it. Elements of Arab culture have to be taken into consideration as well, and the intermingling of the two sets of values and points of view legitimizes the postcolonial interpretation of the film. It should also be noted that the perspective of Disney movies on different cultures is always from the center: films like Aladdin gives an interpretation of the Arab world through the lens of the American Disney. Several further principles are responsible for this phenomenon. Disney films represent other cultures “as if they could not represent themselves” (Said 875)–it is Said’s remark on the Western interpretations on the Orient. The West, referring to the central, describes, teaches and rules over the Orient from an exterior situation. The Orient is the entity under the political and ideological management of the Western. Thus Orientalism is a discourse of power based on ideology, which leads to a manipulated representation on the Orient as it actually is. These representations through the media flood the popular mind. Said elsewhere brings in the example of the Arabs. He claims that they are thought of as “camel-riding, terrorist, hook-nosed, venal lechers whose undeserved wealth is an affront to real civilization” (Said 108). Said’s theory leads to the recognition that it is not the Orient that the audience is presented with; it is just a fake image through the eyes of the Western. Logically, the audience is given a picture of the Western and of Western ideologies rather than an interpretation of the Orient. This phenomenon is a key concept in Disney films. No matter what topic they present, it is ultimately an image on American or Western values that can be distilled from the films.

Gloria Anzaldúa’s notion of the “borderlands” is also a key concept of this paper. Primarily in the context of sexuality, her argumentation articulates that the one who objects the rules, laws and basic values of the given community he/she belongs to, becomes a deviant. Deviants are outcast of the community. “Deviance is whatever condemned by the community. Most societies try to get rid of their deviants” (Anzaldúa 40), she claims. The place where deviants live is at the “borderlands” in Anzaldúa’s concept. Homi K. Bhabha names this relocation “in-between space,” “interstitial space” and “unhomeliness.” According to him, “it is a condition of extra-terrestrial and cross-cultural initiations” (Bhabha 940). Anzaldúa primarily associates deviance with women. She claims that “if a woman rebels, she is a mujer mala (bad woman)” (Anzaldúa 39). The borderland position and the concept of the mujer mala are applied in my discussion about Pocahontas. My argument is that Pocahontas and Smith are deviants because they become outcast of their communities due to their relationship and thus have to stay in the in-between position of the borderlands.

The themes of analysis in this paper are animated movies. Animated films are special cases in film theory since most fictions and documentary films work with three-dimensional, full-sized characters, object, etc. to create a live-action. Animated film, as its name implies is about the creation of series of two-dimensional images by animators. As David Bordwell and Kristin Thomson point out, the most important difference between live-actions and animated films is the production stage (46). Instead of the continuous filming of ongoing actions, animated films are based on the one by one shooting a series of images created by an animator (47). Technology brought about a revolution in animated film production. The greatest change came with the application of computers: slight alterations and swift movements of the images are created with the help if it (48-49). Disney Animation applies the technology of CGI (Computer Graphic Interface) and CAPS (Computer Animation Production System) to make its pictures more life-like1. Even though animation films seemingly lack the connections with the real world (even with the application of computer animation), animated fictions do reflect reality. The umbilical cord that keeps them alive is ideology. According to Louis Althusser, “ideology is a representation of the imaginary relationship of individuals to their real conditions of existence” (693). No wonder that ideology is given a special importance in filmmaking, since films are par excellence representations. Ideology works through the method of interpellation. Althusser claims that individuals become subjects at the moment they are hailed at (interpellated) and they answer to this interpellation (698-699). It is also essential to realize that the relationship between the individual and his/her existence is imaginary, i.e. the individual misrecognizes his/her position. Althusser also points out the importance of the “Ideological State Apparatuses” (701). These includes cultural institutions, like the family, churches, schools, television and cinema. The end of this ideological process is to maintain the existing social order. Robert Stam says that cinema applies this method by fixing its audience “in a position where a particular mode of perception and consciousness appears natural. Both the cinematic apparatus and specific film devices (the perspectival image, point-of-view editing) serve to “subject” the spectator” (136). Kaplan goes further and claims that “Hollywood’s representations unconsciously reflect or embody the colonial imagination” (61). Kaplan’s idea is similar to Said’s theory about the false representation of the Orient due to a problematic Western approach. Referring back to white travelers heading to the Orient, she points out that the Western imagination considered itself the only “civilized” culture (Kaplan ibid.). Though it has changed now, patterns of it remained in the ideological framework of cinema. Kaplan says that the “imperial gaze” is an apparatus that still operates in American culture today to trigger the damaging of inter-racial relations (60).

Story-telling is a way of conveying ideologies to individuals. Jean-François Lyotard in The Postmodern Condition, describes grand narratives or metanarratives as stories about the world that strive to sum it all up in one account (355-356). He finds them problematic and claims that smaller narratives (petits récits) would express a wider range of values. This is exactly what American ideological state apparatuses are striving against in Disney animations. The advertising of the American values gives no place to different ones, or even if it does so, it is only to highlight the contrast and to conclude the merits of American values. Stam in Film Theory suggests the same about Disney animations. He claims, referring to Dorfman, that Disney cartoons are permeated with imperialist racism (Stam 273). Benedict Anderson, though referring to nation-building policies, claims that in them “one sees both a genuine, popular nationalist enthusiasm and a systematic, even Machiavellian, instilling of nationalist ideology through the mass media, the educational system, etc” (Anderson 113-114). Disney’s approach, being nationalist and imperialistic, shares a lot with Anderson’s remark. Story-telling thus has an inestimable role in conveying these ideologies as it functions “as a legitimation of the existing power relations, customs and so on.”2 The trick in Disney animations is that a clear-cut ideology has to be wrapped up for the primarily children audience. Moreover, Disney cannot afford to be politically incorrect. For these reasons, the company sells its movies as the mere opposite of what they are actually about. With this method, Disney captures “all the real world to integrate it into its synthetic universe, in the form of a vast reality show.”3 When the “show” begins with the company’s logo, the subject/the audience is, in an Alhusserian view, already interpellated. In fairy tales, the interpellation is at the beginning of the tale. “Once upon a time…” gives no specific data about the context; its role is to hail the listener. Since Disney movies lack this specific introductory interpellation, the logo of the company takes the place of fairy-tale introduction as an alternative means of interpellation.

Not only the ideological background but also the actual geopolitical situation should be mentioned here. The Gulf War, just like the Vietnam War, generated tension in the United States. Pacifists rallied and protested throughout the country and spread ideas concerning the nonsense of the war and the inability of politicians. These rallies put the United States into the role of the oppressive power and propagated the idea of finishing the war the sooner the better. Tension within the country was obvious. As Alan Nadel points out in his essay, another threat was in the air. The threat of possible nuclear weapons that the Middle East might have gathered throughout the previous years made the people of the United States more uneasy (Nadel 187). This anxiety is further detailed during the analysis of the Disney movie, Aladdin. The film industry started to revive the nation’s grand narrative and to tell it as many times as possible to the doubting millions in the country. One of the main American grand narratives is the discovery of America and the arrival of the first European settlers – which events evoke similar ideas as some of the Gulf War: the collision of two worlds and the consequent battle for land, the issue of victory and that of defeat.

2. Traditional Approaches: Culture and Nature in the Early 1990s’ Disney Animations

In a Hegelian dialectic relation of culture and nature, the film Aladdin is the representation of culture. As Alan Nadel points out in his essay, all the characters have dual natures and are behind at least one disguise (189). My observation is that even this film is a disguise. The advertising of the Western culture is disguised in the frame of the Muslim Middle East. Aladdin is nothing but the sequencing of Western paradigms inserted in an Arab context. Thus, Aladdin is not at all about the Arab world; it is about the power and master position of the Western civilization, and more precisely, of a post-Gulf-war United States. The choice of the context gives way to another kind of colonization marked under the flag of the American manifest destiny. The aim of it is to make the (primarily children) audience believe that such distinct cultures as the Arab incorporate almost exclusively American elements. Hence, the authentic Arab cultural context gets a fake interpretation. Slavoj Žižek claims that today’s multiculturalism experiences the Other deprived of its Otherness (11). He offers for this the example of the decaffeinated coffee, which is deprived from its very essence: caffeine. The idealized Other has the same pattern: its reality is deprived of its substance. As it is mentioned in the “Filmmaker’s Audio Commentary”4 Aladdin’s character was based on the figure of American actor Tom Cruise5; Jasmine’s face came from animator Mark Henn’s daughter and her figure was drawn on the basis of a careful study on professional American models6. Most persons Genie embodies are famous American showmen, actors and media gurus. The importance and different roles of Genie are discussed later. Intertextual references to previously released Disney cartoons (Pinocchio,7 The Little Mermaid,8 The Beauty and the Beast9) on the one hand are humorous; on the other hand, suggest the borderless influence of the American media on film production.

The complex relationship between of the United States and the countries of the Middle East is present in Aladdin. The frame of the Western culture on the Muslim world mirrors a specific cultural imbalance. In the filmic narrative, the instability of power is understood as a delicate question. There seems to be no one who has full independency. The Sultan and Jafar are equally dependent on each another (by hierarchical position and hypnotizing); Aladdin and Jasmine are confined by the law concerning their possible marriage and by their social statuses; Genie is the slave of his master – however free he seems to be (Nadel, 190). The actual political background shows a parallel to this instability. Nadel points out that after the end of the Gulf War in March 1991, a sense of insecurity was growing concerning Iraq’s nuclear weapon capacity (187). Although the United States liberated Kuwait and won the Gulf War, its position was fragile due to Iraq’s (possible) hidden nuclear weapons.

Nadel claims that Genie’s enormous power is equivalent to the atomic power inasmuch as both have “phenomenal cosmic power in an itty-bitty living space.”10 The oil beneath Arabia gave such wealth to the Middle East that the acquisition of Western technology to produce nuclear weapons seemed to be frightening (Nadel, 192). In other words, whoever has Genie has power. This delicacy of power threatens with losing of the ruling position. Kaplan says that this anxiety results in an imperial gaze that creates four types of images of others. One of them is imaging minorities as immoral or simply evil, who are not capable to distinguish between right and wrong (Kaplan, 80). Aladdin is a good example to this kind of image on Muslim people. The evil characters in the film have typical, Middle-Eastern features (Jafar is very tall and silent; Iago is very small and loud; the apple man who wants to cut off Jasmine’s hand is an enormous man with giant hands11). As opposed to them, Aladdin, Jasmine, the Sultan and Genie have Western profiles.

The magnification of these characteristics is applied to make it easy to recognize the negative part. As Ward claims, “Disney villains are usually coded by color or shadow [. . .] or by excess” (40). The distinction between good and evil is articulated, in Aladdin, as well, by an even more spectacular method: coloring. The conscious usage of red and blue symbolizing evil and good respectively recurs several times in the movie.12 Red and blue as binary oppositions are different from the general, complementary color usage. However, in the historical and political context of the United States they are best known as the opposites of each other: the Republican and the Democrats. I do not claim here that the usage of red for the evil characters might suggest an opposing view-point to the Republican Party, for instance. My point is only that the choice of the two colors implies an essentially American atmosphere since the nature of this binary opposition is not universal, but rather US specific. Jafar and Iago are in red; under Jafar’s hypnotization everything turns into red, even his cellar in the palace is of red color. This association of the red color and the evil has its root in the Judeo-Christian culture. Satan is envisioned to have red skin, hell is commonly thought about as red. The apple in the Garden of Eden (associated with the paradigm of the sin) is red. It was the Serpent who brought about the fall in Genesis; Jafar can never be seen without his stick that has the face of a serpent carved in it. Aside from the cultural codes, the red color refers to heat as well, which is very typical to the climate of the Middle East. Blue, on the other hand, has a reference to water. The necessity of water in the Middle East is obvious (oases), in other words, the good has to be there to counterbalance (or defeat) the bad side of things. Aladdin, Jasmine and Genie are ‘blue’ characters and it is not a coincidence that the blue/good characters are the ones who has Western/American features.

Aladdin

Good Characters

Evil Characters

The duality of the Western and the Arab culture is also present in Disney’s method of drawing. Unlike the previously released Disney animations, Aladdin is drawn mostly with curvy, thick and thin lines. On one hand, this method of drawing resembles the typical Arabian calligraphy. On the other hand, the American caricaturist, Al Hirschfeld applied the somewhat same distinctively bold, curvy lines with little or no shading in his drawings13 which suggests Westernized shapes. The form of the characters thus, are based on Hirschfeld’s caricatures, the surroundings have the Arabian calligraphic elements.14 Therefore, both in its shape and message, Aladdin is heavily loaded with cultural codes. In the triangle of the three films further analyzed, Aladdin is, thereof, associated with the idea of ‘culture.’

The Lion King is most often referred to as a moral ‘educator’ on the issue of responsibility, family relationships, life and death (Ward, 30). In my view, however, The Lion King is analyzed as the representation of nature seen as opposite of culture. It is widely known that Walt Disney Pictures produces animated movies mostly with animal characters. These films take place in urban settings (e.g. 101 Dalmatians) or in the wilderness under the influence of the man (e.g. Bambi). No animated movies on animals were produced without the presence of the man previous to The Lion King.15 This film takes place in Africa that used to be a less known part of the world, an entity characterized seen as “dark,” unknown. This dark, mysterious feature of the scenery is enhanced at the very beginning of the movie, too. The unusual, black background provides the main scheme-scene for some seconds and then the common light blue logo of Walt Disney Pictures logo with the shooting star creeps into the screen as the sign of Western civilization that lurks from behind. The stars flies by and the screen goes blank again.16 This method suggests mystery and oddness that are magnified by the unusual silence during the presentation of the logo. This silence is broken by a frighteningly loud and harsh African chant.17 The title of the film appears after more than four minutes, which is exceptionally long time for contextualization. This length is needed to give enough time to the audience to be emerged in the world of Africa. The title appears on the same black background as the logo did. However, it lacks any typical Disney decoration; it is just the mere title that appears. All these unusually simple features serve to introduce a similarly unusual context: Africa.

As pointed out previously, the choice of color is of special importance in Disney animations. In The Lion King, however, it would be difficult to categorize the characters on the basis of given colors. While in Aladdin red and blue represent evil and good respectively, The Lion King works only with shades. Colors matter less. The light shade of colors is used in the cases of good characters and secure places. The evil characters and the ‘forbidden’ places are colored with dark shades. This method in Aladdin is less sophisticated but in The Lion King is necessary because the depiction of the wild, rampant nature needs varying colors. The application of vivid colors in connection with the African setting refers to the power of nature. The distinct colors of blossoming trees and bushes and the hundreds of shades of green are mirroring the inestimable power of nature. Rain (as a form of water) is here a recurring theme. It brings life to plants and animals and quenches the fire; rain is responsible to birth and renewal whereas fire refers to destruction (Ward 21). Nature works on the whole scale of life and determines everything within the film itself, too.

The rules of nature are articulated not only in its representation. The circle of life is the spirit of the movie in two main respects. The first incorporates life and death and everything in-between, in general.18 The second is a narrower reading: it refers to the food chain, which is very often mentioned in the film. Antelopes are eaten up by lions whose bodies become grass when they die; grass is eaten up by antelopes.19 The constant threat of being killed (by another animal) is present throughout the whole film. This theme is rarely applied by Disney; here it emphasizes the cruel laws of survival. The narrativity of the film follows a circular pattern tailored after the circle of life. It starts and ends with the birth of the new king. The scenery and the music are the same at the beginning and at the end; the audience is reminded of the beginning of the film and thus the story can start again… This approach of narration cannot be found in Aladdin: its storyline goes from point A to point B, and thus would be best illustrated with a line. The Lion King, can be visualized in the shape of a circle. These two shapes are exactly the ones that describe the different time-perspectives of Western civilization and non-Western tribes.20

Pocahontas is the synthesis of Aladdin and The Lion King. It incorporates the discussed features of both movies, by involves a combined idea of nature and culture prominent through the issue and the perspective of time. Since the linear and the circular concepts of time can hardly be used here at the same time, the filmmakers decided on the application of the linear version21 in this film, but embedded the other significant shape, too: the line and the circle are combined together in the compass or the “spinning arrow.”22 This recurring prop has a symbolic value, that is, the meeting of the two worlds. It is the compass that brings the British to the New World, and it is the “spinning arrow” (later identified with the compass) that “is pointing [Pocahontas] down to [her] path,”23 which turns out to be the encounter with the colonizers. The core of the story is told in that small object.

The story itself is based on the well-known legend of Pocahontas. Filmmakers have changed several elements of this story and reformulated the life of Pocahontas into a specific Disney version. The question of historical accuracy can be a problem here, which is, nowadays a ‘charge’ against Disney adapting the story of Pocahontas. Pocahontas is the first animated movie of the company that has historical relevance. The leading characters are real figures and the given situation of colonization is a historically recorded event. Yet, several data are changed—or neglected— because, as supervising animator Glen Keane puts it, “[the filmmakers] had to decide between being historically accurate or socially responsible” (Ward 37). The core of the story is the inevitable clashing of different values and thus, war between the British and the American Natives. In a wider perspective, the expected outcome of culture (cf. Aladdin) and nature (cf. The Lion King) is the conflicting of them (cf. Pocahontas). For this reason, Pocahontas can be interpreted as the synthesis of Aladdin and The Lion King. As I have previously pointed out, the idea of culture is associated with the Western world (the colonizers, in Pocahontas), while the idea of nature refers to the Native people. The idea of nature associated with the Natives is that Pocahontas is built upon the significance of nature on the side of the colonized people; nature is the basic framework of their culture. The tension between the ideas of culture and nature is dissolved in the story of Pocahontas; therefore the audience is faced with images and music that equally share the concepts of the Western and the Native worlds.

One of these features is the characterization of Pocahontas. Her body, like that of Jasmine, was based on American models, but is “different than the Caucasian kind of look,”24 as Glen Keane, supervisor animator of Pocahontas, claims. She has narrower eyes and a strict line of chin, opposed to previous Disney female character with the typical big eyes and smooth lines of the face. Pocahontas is “more of a woman than a teenager,”25 and with this change comes sexuality. This is actually not a new topic to Disney. Elizabeth Bell points out the fact that Disney artists capture femininity and, at the same time, also capture “performative enactments of gender and cultural codes for feminine sexuality” (Bell 120). Pocahontas’s voluptuous body reflects the Western male vision on exotic women: she has the body of a Western woman but has the exotic features that make her other than Western women. The idea of being drawn from a Western male point of view actually appears in the movie. When John Smith glances at Pocahontas, he does so not directly, but in the reflection of the water in his hand.26 This involves the very idea that he cannot look at Pocahontas as she is; she is seen by him indirectly through his Western view. In general, it can be stated that Natives are presented the same way in the film. The perspective of the Disney animators on Native people is highly influenced by their position as Westerners.27 When a Disney animation is made on another culture, it cannot be produced without the interference of Western paradigms. This is the theoretical reason why Disney heroines are always characterized with the features of Western women and the good characteristics, accordingly, are associated with beauty according to Western concepts, even though the given character is of another culture.

A postcolonial notion is significant in Pocahontas: the issue of borderlands. This place is the in-between place between two communities. According to Gloria Anzaldúa, those people are forced to live in the borderlands who are considered deviant. In Pocahontas, there are two deviants who live in the borderlands: Pocahontas and John Smith. Both are deviant to their community, mostly because they have a conspiracy with the other coming from another community. Both of them disobey the laws they are ordered to (Pocahontas is not allowed to leave the village; Smith is a scout with the mission to hunt down Indians.) Pocahontas’ position within Anzaldúa’s concepts is more peculiar. Anzaldúa claims that a woman has three choices: becoming a nun, a prostitute or a mother. Pocahontas’ choice is rather the second one. Her position in the community could be best described by Anzaldúa’s term “mujer mala” (bad woman).The place where they meet is the river, a natural and a symbolic boundary. It is also significant to know that the warfare between Natives and the British originates from the borderland. The pretext of the fighting is the murder of Kocoum at the riverside. People who neither belong to a community nor to the other are forced to live in between the two communities, that is, on the borderlands. This is the most dangerous zone, since the grievances of the two sides are clashing there (Anzaldúa 42-43). The original version of Pocahontas contained a song that later was abandoned. It was called “In the Middle of the River.” As previously mentioned, this song has a lot in common with Anzaldùa’s thesis on the borderland position. The following excerpt explains why:

POCAHONTAS: My mother used to say that whenever there’s anger and hatred on both sides of the river, you can always find the place of peace in the middle of the river.

JOHN: The middle of the river?

POCAHONTAS: When the land is full of anger, when the fists of hate are shook, when there is no common ground to be found, where to look?

JOHN: We will meet in the middle of the river; we will hide in the heart of the cloud. If that’s the place where we can be together, we’ll be there somehow. […] we’ll be living in the middle of the river.

POCAHONTAS & JOHN: I don’t know what they hate so much about you. I don’t know what they cannot forgive. All I know is I couldn’t live without you, though we live in the middle of the river. […]

POCAHONTAS: If the is no land for us, where can we look?

JOHN: In the middle of the river.28

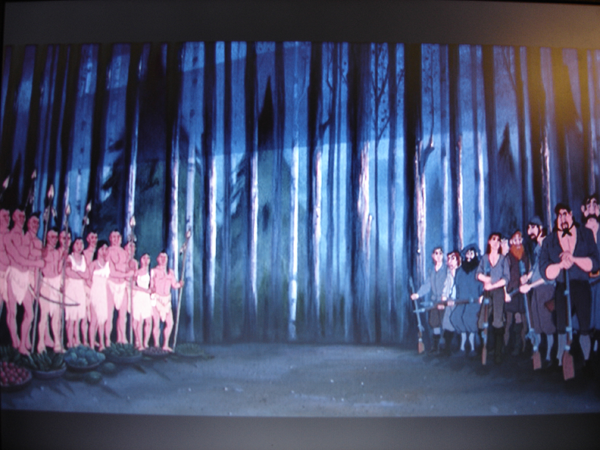

The audience is shown no precise reference to the past of Pocahontas’s mother, but this song gives some hints. In Alzaldúa’s essay, it is the woman who becomes a deviant (cf. mujer mala); thus it is suggested that Pocahontas’s mother had the similar deviant feature as her daughter has now. The lyrics, although referring to a river, precisely define the position of the borderland: between the two banks, in the water. Geographically speaking, it might as well refer to the Atlantic Ocean as a borderland between the European and the American continent. The same idea appears towards the end of the movie. Pocahontas and Smith are saying their farewells surrounded by the British and the Natives. When deciding whether to leave or stay, Pocahontas looks at the people around them, who are standing divided: in the left side of the picture the Natives, on the right, the British are standing in line.

Between them, there is the borderline resembling to a river or ocean (in its color).29 It is also important to note that on both sides, people are holding weapons in there hands, suggesting their hostility towards the other. It is also significant that the issue of deviance and the borderline has not occurred before. Aladdin and The Lion King separately stand for the two clashing sides: culture and nature. When the two (are threatening to) come together, the borderline is made at once, and the ones outcast of the two sides are pushed to that land.30

The climax of the film is the scene of war – a war that is never fought in the movie. Instead, fierce marches are sung by the two sides. This song “Savages” does not lack political incorrectness; moreover, it is nothing but the shocking anger and grievance felt against the other.31 Since the war is not fought because of the heroic deed of Pocahontas and because it would hardly fit in the framework of Disney to show bloody shots of wars, the song has to articulate the opposition as much as it can. Natives are called “filthy little heathens”32 by Ratcliffe who reminds his men that there is “what you get when races are diverse.”33 It is also heavily emphasized that the difference between the two peoples are the real cause of the war: “They’re not like you and me / which means they must be evil”34 (“which mean they can’t be trusted”35). This line precisely recalls the characterization of Arab men in Aladdin and of villain animals in The Lion King.

3. Cultural Codes, Cores and Choirs: Synthesizing Characters and Film Music

All three movies have a so-called synthesizing character, who/which is the synthesis of all other characters and personifies the one who carries the essence of the given film’s context. These specifically synthesizing characters symbolically represent culture and/or nature. It is not only the characters which bring the core of the film but film music, as well. Disney works with the most acknowledged composers and lyricists to attain such heightened levels of intellectual and emotional associations as pictures do. Stam refers to Brown, who argues that “music, as a non-iconic medium when accompanying the other tracks of film, can have a generalizing function, encouraging the spectator to receive the scene on the level of myth, while also triggering a “field of association” likely to foster emotional identification” (Stam 219-220). Disney animations usually work with diegetic, semi-synchronous, post-synchronized music. Songs hardly ever come from outside, they are usually sung by a given character within the course of events. They “lubricate the spectator’s psyche, oil the wheels of narrative continuity [. . .], direct emotional responses and regulate our sympathies” (Stam 221). The issue of the synthesizing characters is intertwined with film music, more precisely with the opening scores and introductory songs. Film music is nothing but the traits of these characters. My assumption here is that the synthesizing characters are just as much the core of the plot and of the movie as film music is. In Aladdin, the synthesizing character is Genie.  The opposition of Aladdin and Jafar is dissolved in the character of Genie. Genies are originally imaginary spirits in ancient Middle Eastern stories and the concept of this spirit with magical power has, thus an Arab reference. Genie in Aladdin is endowed with the mixed profile of a variety of American celebrities, actors and showmen, like Jack Nicholson and Grucho Marx. Genie’s different personality (made visible through a couple of intertextual references to American films), however, make him the most American character whereas his role should have the most essential references to the Arab culture. As Nadel points out, Genie’s character is more complicated since it is also associated with the image of the atomic power, as a cloud-like steam figure that it comes out from its bottle. He symbolizes the desert (that contains oil that makes a profit, which enables its countries to have nuclear weapons) and with him the good as well as the bad can gain power over the other (Nadel 192). When Jafar is turned into a genie,36 he “swells to an apex of dark energy surrounded by the halo of an atomic insignia” (Nadel 193). The metamorphosis of Jafar creates a hellish picture: the dominant color is red, the fire is burning and the snake is present.

The opposition of Aladdin and Jafar is dissolved in the character of Genie. Genies are originally imaginary spirits in ancient Middle Eastern stories and the concept of this spirit with magical power has, thus an Arab reference. Genie in Aladdin is endowed with the mixed profile of a variety of American celebrities, actors and showmen, like Jack Nicholson and Grucho Marx. Genie’s different personality (made visible through a couple of intertextual references to American films), however, make him the most American character whereas his role should have the most essential references to the Arab culture. As Nadel points out, Genie’s character is more complicated since it is also associated with the image of the atomic power, as a cloud-like steam figure that it comes out from its bottle. He symbolizes the desert (that contains oil that makes a profit, which enables its countries to have nuclear weapons) and with him the good as well as the bad can gain power over the other (Nadel 192). When Jafar is turned into a genie,36 he “swells to an apex of dark energy surrounded by the halo of an atomic insignia” (Nadel 193). The metamorphosis of Jafar creates a hellish picture: the dominant color is red, the fire is burning and the snake is present.

Genie’s role in the film is versatile. He is by definition a slave to his present master, but at the same time, has the power to change forms and, thus, to change the course of events. He depends on his master, just like his master depends on him. There is one thing Genie cannot be exceeded in: knowledge. He knows all cultural references and moreover and seems to know even the very script of the film (he brings in the script of the on-going film lines to Aladdin37). Moreover, it is Genie who ultimately frames the movie. The first character that appears is the figure of an incipient narrator: an Arab merchant. He introduces the story of Aladdin but fails to return at the end to close the frame. Instead, Genie appears, tears up the reel and says “Made you look.”38 The narrator (wearing a cloak with the same blue color as Genie’s) is, at the beginning, dubbed by Robin Williams, who is Genie’s actual voice. Interestingly, even the animator of these two characters is the same: Eric Goldberg. Genie’s role as main narrator makes him the most essential character. He is not a god-like figure (since he also has the role of the slave), but he definitely transcends and incorporates all space and time. Genie has not one specific form because he is a shape-shifter. He cannot be described with any geometrical form, whereas the other characters are based on a more strict body-geometry. Aladdin’s body resembles two triangles; Jafar is two perpendicular lines (like the letter T); the Sultan has an egg-shape. Genie incorporates all these forms and has even more shapes. His transcendental figure is closely connected to culture: the genie-essence is related to the myths and legends of the Arab world, but the forms he takes and the people he embodies are from the American and Western culture.

As I have articulated at the beginning of this part, the figure of synthesizing characters and film music are very closely connected to each other. Introductory songs especially are means to contextualize these movies and to give the very essence of culture and/or nature appearing in them. In introductory songs, the musical pattern has a distinctive feature that characterizes the context of the film. In the case of Aladdin, this musical feature is the typically Arab serpent-charming melody. Similarly to the Arabian calligraphy in the method of drawing, the Arabesque style in music refers to the culture of the context. Music and the animation together enhance the effect: in the title sequence and song of Aladdin, the lines of the calligraphy and the same similarly curvy line of the music39 together introduce the audience to a “faraway place.”40 This song is the “Arabian Nights,” the introductory song of Aladdin.41 The form is connected to the culture of the Middle East, but the lyrics carry the criticism of that world. The Arab merchant (the narrator/Genie) sing a song about his homeland. Yet, he refers to the place as if he were an outsider: “Oh, I come from a land, from a faraway place.”42 The first version of the song turned out to be more than politically incorrect. For this reason the line “Where they’ll cut off your ear if they don’t like your face”43 was rephrased to the neutral line of “[W]here it’s flat and immense and the heat is intense.”44 The following line makes clear that the lyrics are not from the Arab merchant’s point-of-view: “It’s barbaric, but hey, it’s home!”45 The song “Arabian Night” is the perspective of the Western culture on the Middle East. The introductory song in Aladdin, hence, is quite similarly constructed to the character of Genie. The form of Genie and the form of the song bear Arab cultural references, whereas the content of Genie (the different Western personalities) and the content (lyrics, point-of-view) of the song are saturated with American cultural elements.

The synthesizing character in The Lion King is Rafiki, a mandrill, often referred to as a baboon, who is the one who carries the essence of Africa, on the one hand, and on the other, dissolves the dichotomy of Simba, the protagonist and Scar, the antagonist.  His character is that of the medicine men in primordial cultures. He conducts the rituals, stands beside the leader and knows the secrets of the community. He is a highly esteemed figure although his behavior and his rhetoric are odd. He is the oldest member of Pride Land, his esteem is due to this feature of his.46 Rafiki always brings along his cane with the orange rattle on it. Wherever he goes, the rhythm of the rattle and the rhythm of Africa are with him (he can also be an embodiment of the African trickster figure, who is mainly a monkey). When he initiates Simba to the hidden knowledge of his own, African community, he shakes the rattle above Simba’s head and smears the juice of the rattle on his forehead. When a new life47 or a new reign48 starts, Rafiki gives his blessings by shaking the rattle. When an era closes down (at Mufasa’s death49), the rattle remains silent. Rafiki conjures up the rhythm of Africa when he chants the song “Asante Sana.” This song is an existing Kenyan chant, but which here has a humorous meaning: “Thank you very much, squash banana, you’re a baboon, I am not.”50 No other animals can be connected with the rhythm in this film as much as Rafiki, therefore, he can be said to be the ‘ambassador’ of Africa. Unlike Genie in Aladdin, he is not a transcendental but an animal character. It is claimed that the scene between Rafiki and Simba as the new king51 was influenced by the relationship of King Arthur and Merlin.52 The relationship between Rafiki and Simba does reflect the one between Merlin and King Arthur in general, but it cannot be claimed that Rafiki is the strict analogue of Merlin. Merlin was a magician in the Arthurian legend and in this respect is rather like Genie in Aladdin. Rafiki has no power over space and time and has no mighty power as Genie has. His power lies in his age and his wisdom. These enable him with the necessary means to convince Simba to return and take his place on Pride Rock. Rafiki, like an early psychoanalyst, brings Simba back to his past to find out where he went wrong. Simba’s way back to his past is described in the same manner as it is described when he leaves the community. He creeps away from the hyenas under thorny bushes,53 and follows Rafiki to the lake through the same route with the same movements but in the opposite direction.54 Rafiki’s importance is in his ability to make Simba realize his tragic flaw – the death of his father. Only with Rafiki’s help can Simba face his past and return to the community he belongs. Ultimately, Rafiki is the catalyst that influences the course of events and brings everything back to its right order. In this respect, he has the same circular role as Genie but it is important to see the nature of the difference between them. Genie is a transcendental figure, who lives in the realm of imagination and his mere existence depends on faith in a specific culture. Rafiki is an animal character with no visible transcendental value. He is a medicine man-like, philosophical figure of the oldest creature, who is highly esteemed in the community of animals due to his age and knowledge. His existence does not depend either on faith or culture, but mostly on nature.

His character is that of the medicine men in primordial cultures. He conducts the rituals, stands beside the leader and knows the secrets of the community. He is a highly esteemed figure although his behavior and his rhetoric are odd. He is the oldest member of Pride Land, his esteem is due to this feature of his.46 Rafiki always brings along his cane with the orange rattle on it. Wherever he goes, the rhythm of the rattle and the rhythm of Africa are with him (he can also be an embodiment of the African trickster figure, who is mainly a monkey). When he initiates Simba to the hidden knowledge of his own, African community, he shakes the rattle above Simba’s head and smears the juice of the rattle on his forehead. When a new life47 or a new reign48 starts, Rafiki gives his blessings by shaking the rattle. When an era closes down (at Mufasa’s death49), the rattle remains silent. Rafiki conjures up the rhythm of Africa when he chants the song “Asante Sana.” This song is an existing Kenyan chant, but which here has a humorous meaning: “Thank you very much, squash banana, you’re a baboon, I am not.”50 No other animals can be connected with the rhythm in this film as much as Rafiki, therefore, he can be said to be the ‘ambassador’ of Africa. Unlike Genie in Aladdin, he is not a transcendental but an animal character. It is claimed that the scene between Rafiki and Simba as the new king51 was influenced by the relationship of King Arthur and Merlin.52 The relationship between Rafiki and Simba does reflect the one between Merlin and King Arthur in general, but it cannot be claimed that Rafiki is the strict analogue of Merlin. Merlin was a magician in the Arthurian legend and in this respect is rather like Genie in Aladdin. Rafiki has no power over space and time and has no mighty power as Genie has. His power lies in his age and his wisdom. These enable him with the necessary means to convince Simba to return and take his place on Pride Rock. Rafiki, like an early psychoanalyst, brings Simba back to his past to find out where he went wrong. Simba’s way back to his past is described in the same manner as it is described when he leaves the community. He creeps away from the hyenas under thorny bushes,53 and follows Rafiki to the lake through the same route with the same movements but in the opposite direction.54 Rafiki’s importance is in his ability to make Simba realize his tragic flaw – the death of his father. Only with Rafiki’s help can Simba face his past and return to the community he belongs. Ultimately, Rafiki is the catalyst that influences the course of events and brings everything back to its right order. In this respect, he has the same circular role as Genie but it is important to see the nature of the difference between them. Genie is a transcendental figure, who lives in the realm of imagination and his mere existence depends on faith in a specific culture. Rafiki is an animal character with no visible transcendental value. He is a medicine man-like, philosophical figure of the oldest creature, who is highly esteemed in the community of animals due to his age and knowledge. His existence does not depend either on faith or culture, but mostly on nature.

The musical score in The Lion King is based on rhythm, unlike in Aladdin where the Arabesque is associated with melody. The essence of Africa, of African tribal lifestyle, is in its rhythm. As previously pointed out, Rafiki’s constant rattling is responsible to maintain the African context. Hans Zimmer, composer of The Lion King, says the musical inspiration to the film was gained from the chants of indigenous African tribes and actually a Zulu choir sang the chants of The Lion King.55 Like in Aladdin, this film also has an introductory song: “Circle of Life.”56 The song starts out with the opening call of South-African born artist, Lebo M. The one-minute chant “Nants’ Inconyama” places the audience into the frame of the continent. As Zimmer remarks, with Lebo’s chanting “you know that you’re not in Kansas anymore.”57 Lebo is backed up by the Zulu choir conducted by him, and their chanting accompanies the “anthem”58 “The Circle of Life.” The song is almost four minutes long and except for a half-minute bridge, lacks musical instruments responsible for melody. Melody creeps into the song only by the entrance of Carmen Twillie’s voice. Rhythm is dominant, brought about not only with percussions but by the continuous chanting of the African choir. The lyrics of the song were written by Tim Rice, but have nothing to do with the African context. Life, death and our place in the world are independent of it. Not only the character of Rafiki but also the introductory song is associated with the idea of nature. The context of Africa is best illustrated with this special rhythm that can be found not only in the music but also in the synthesizing character of Rafiki.

The synthesizing character in Pocahontas is Grandmother Willow. Her existence (as a tree) is a natural state, but her existence as Grandmother Willow depends on the belief of the tribe. Therefore, her character recalls a complex mixture of Genie and Rafiki. In this respect, she synthesizes not only the British and the Natives but the two, previously discussed synthesizing characters, as well. Grandmother Willow is actually a 400 years old tree. “Grandmother” refers to her age and to the family lines and ancestors of the people in the tribe. (She also takes the role of the mother in the case of Pocahontas.) “Willow” conjures up the image of a weeping willow (which she indeed is), and reminds the audience to the word “widow.” Widows, by definition, live alone, like Grandmother Willow. She lives unaccompanied, alone, far from the tribe. In this respect, she is similar to Rafiki, who lives outside the community but for it. Grandmother Willow has her roots in the river, which provides the symbolic value of the borderline space in the film. This is the place where Pocahontas and John Smith meet most of the time. Their meeting is regarded as a sinful deed, a deliberate disobedience against the orders of their communities. Where Pocahontas and Smith meet is a no (wo)man’s land, a place where the two can be who they indeed are: interstitial characters. This context with the presence of the tree (Grandmother Willow) is similar to that of the Garden of Eden, where the first humans, Adam and Eve lived and from where their knowledge and sin derive. In other words, a Western paradigm with Native concepts is implied in the role of Grandmother Willow. The most important role of hers is her presence whenever a change occurs in the story (catalyst). When Pocahontas and Smith are not listened to by their people, it is Grandmother Willow who shows them the ripples on the surface of the water as the analogue of the need to stand up and speak up: “[S]omeone has to start [the ripples],”59 she says. This lesson teaches Pocahontas and John to act against their roles and start negotiations with the others, or at least get them to sit down and talk. Grandmother Willow reappears at the morning of the planned execution of John Smith. She tells Pocahontas that her path leads to him (the compass appears again, symbolizing the coexistence of the Natives and the colonizing British.) This idea is in accordance with that of Franz Fanon, who points out that Western discourses of power understand the desire of the woman of color to be “colonized” by a white man (Fanon 41-63). The path of the Native American Pocahontas leads to the white John Smith, analogously: coexistence of the colonizers and colonized is desired.

The synthesizing character in Pocahontas is Grandmother Willow. Her existence (as a tree) is a natural state, but her existence as Grandmother Willow depends on the belief of the tribe. Therefore, her character recalls a complex mixture of Genie and Rafiki. In this respect, she synthesizes not only the British and the Natives but the two, previously discussed synthesizing characters, as well. Grandmother Willow is actually a 400 years old tree. “Grandmother” refers to her age and to the family lines and ancestors of the people in the tribe. (She also takes the role of the mother in the case of Pocahontas.) “Willow” conjures up the image of a weeping willow (which she indeed is), and reminds the audience to the word “widow.” Widows, by definition, live alone, like Grandmother Willow. She lives unaccompanied, alone, far from the tribe. In this respect, she is similar to Rafiki, who lives outside the community but for it. Grandmother Willow has her roots in the river, which provides the symbolic value of the borderline space in the film. This is the place where Pocahontas and John Smith meet most of the time. Their meeting is regarded as a sinful deed, a deliberate disobedience against the orders of their communities. Where Pocahontas and Smith meet is a no (wo)man’s land, a place where the two can be who they indeed are: interstitial characters. This context with the presence of the tree (Grandmother Willow) is similar to that of the Garden of Eden, where the first humans, Adam and Eve lived and from where their knowledge and sin derive. In other words, a Western paradigm with Native concepts is implied in the role of Grandmother Willow. The most important role of hers is her presence whenever a change occurs in the story (catalyst). When Pocahontas and Smith are not listened to by their people, it is Grandmother Willow who shows them the ripples on the surface of the water as the analogue of the need to stand up and speak up: “[S]omeone has to start [the ripples],”59 she says. This lesson teaches Pocahontas and John to act against their roles and start negotiations with the others, or at least get them to sit down and talk. Grandmother Willow reappears at the morning of the planned execution of John Smith. She tells Pocahontas that her path leads to him (the compass appears again, symbolizing the coexistence of the Natives and the colonizing British.) This idea is in accordance with that of Franz Fanon, who points out that Western discourses of power understand the desire of the woman of color to be “colonized” by a white man (Fanon 41-63). The path of the Native American Pocahontas leads to the white John Smith, analogously: coexistence of the colonizers and colonized is desired.

The film music of Pocahontas can be understood as the essential “sum” of the filmic narratives from Aladdin and The Lion King. Just like Grandmother Willow, who can be viewed as the synthesis of Genie and Rafiki. Since Pocahontas is about two different worlds, the process of contextualization is at two places and thus accompanied by two different songs. The opening scene is in the 17th century Britain, where the Susan Constant with its crew is preparing to leave the harbor. The first introductory song is “The Virginia Company,”60 which is like a recruiting music. The lyrics sums up the goals and ends of the voyage: “For the new world is like heaven, / And we’ll all be rich and free, / Or so we have been told by the Virginia Company.”61 The song ends with a serious storm over the sea, which is the first sign that the merits of the new world might not be as easy to grasp as it was sung in the introductory song of the British.

The scene dissolves in thick fog and a distant drum can be heard.62 This is the opening of the second introductory song. It implies the title sequence as well. The drumming and chanting accompany the song “Steady as the Beating Drum.”63 This song introduces the audience to the world of the Native Americans, precisely the life of the Powhatans. The form of the song relies on the sound of the drum, which refers to the rhythm of the Native tribe. The importance of the drums is emphasized in the repeated line of “Steady as the beating drum,” which refers to the harmonious, peaceful life of the Natives. The cyclical repetition, as a determining factor in their lifestyle is referred to with the same line: “Seasons go and seasons come / Steady as the beating drum.”64 Unlike the first introductory song, the values underlined are not related to money, glory or power, but refer to the basic laws and beliefs of the tribe. It also implies a religious aspect as well “Oh, great spirit, hear our song / help us keep the ancient ways, / Keep the sacred fire strong.”65 The ongoing images depict the lifestyle of the Natives, including their work, roles and kinship relations among the tribe. The application of two introductory songs makes the audience face two distinct worlds and contexts at the outset of the movie.

The roles of the synthesizing characters are not only significant in the films they are participating in, but also in their relationship to one another. Within the films, their primary role is to ease and dissolve the tension between the protagonist and the antagonist, and to synthesize the differences of two opposing sides. Their other significant role is that they are or carry the essence of the contexts of the films they are situated in. The three characters’ relationship to one another works in a similar pattern. It is Grandmother Willow who is the ultimate synthesizing character because her figure is originated both from Genie and from Rafiki; nature and transcendental issues come together in the character of Grandmother Willow. This synthesis works with film music and introductory songs, as well. Since they place the audience in a given context, they carry the complex, intertwined ideas of culture and nature.

4. “Disney-sembling” the Mythic America

The global political situation at the beginning of the 1990s caused an urge to revive the origins of the American nation. Walt Disney Pictures revives it by the three films mentioned. I claimed that the films are in a symbolic relationship to one another based on the dialectics of culture and nature. I also pointed out that the films are actually about the American values represented in different territories and thus convey a nationalist accent. During the composition of the present paper, the idea has arisen whether the consequences drawn here can be applied to further Disney animations from a later period. I suppose that these results can be accounted for only in the era of the early 1990s. Later on, after the release of Pocahontas, a shift can be observed in Disney’s approach. In 1996, The Hunchback of Notre-Dame brings in “the reverse:” the myth of the protagonist’s handsome look is shattered by the characterization of Quasimodo. The mere choice of topic for adaptation signals the “wind of change.” In 1997, Mulan, the heroic story of a Chinese girl has irreversibly changed the profile of Disney. Turning from nationalist accent to postnationalist ideas, Walt Disney Pictures definitely incorporates trends that are culturally and politically dominant. Globalization and internationalism are becoming key concepts of the third millennium Walt Disney Productions. “The postnationalist is not a new critical practice; it builds upon previous work, within and outside the American Studies that is critical of U.S. hegemony and the constructedness of both national myths and national borders” (Rowe 3). This quotation supports the idea that Disney has given up building American or Americanizing myths and has turned to a global, international level and representation, which is a topic for another, further research.

Appendix – Lyrics

Appendix 1/1 – Aladdin (1992)

Arabian Nights

From Aladdin

Music and Lyrics by Alan Menken

Oh I come from a land, from a faraway place

Where the caravan camels roam

Where it’s flat and immense

And the heat is intense

It’s barbaric, but hey, it’s home

When the wind’s from the east

And the sun’s from the west

And the sand in the glass is right

Come on down

Stop on by

Hop a carpet and fly

To another Arabian night

Arabian nights

Like Arabian days

More often than not

Are hotter than hot

In a lot of good ways

Arabian nights

‘Neath Arabian moons

A fool off his guard

Could fall and fall hard

Out there on the dunes

Appendix 1/2 – The Lion King (1994)

The Circle of Life

From The Lion King

Music and lyrics by Tim Rice and Elton John

From the day we arrive on the planet

And blinking, step into the sun

There’s more to see than can ever be seen

More to do than can ever be done

There’s far too much to take in here

More to find than can ever be found

But the sun rolling high

Through the sapphire sky

Keeps great and small on the endless round

It’s the circle of life

And it moves us all

Through despair and hope

Through faith and love

Till we find our place

On the path unwinding

In the circle

The circle of life

Appendix 1/3 – Pocahontas (1995)

The Virginia Company

From Pocahontas

Music by Alan Menken and Stephen Schwartz

In sixteen hundred seven

We sail the open sea

For glory, God, and gold

And The Virginia Company

For the New World is like heaven

And we’ll all be rich and free

Or so we have been told

By The Virginia Company

For glory, God and gold

And The Virginia Company

On the beaches of Virginny

There’s diamonds like debris

There’s silver rivers flow

And gold you pick right off a tree

With a nugget for my Winnie

And another one for me

And all the rest’ll go

To The Virginia Company

It’s glory, God and gold

And The Virginia Company

Steady as the Beating Drum

From Pocahontas

Music and lyrics by Alan Menken and Stephen Schwartz

Hega hega ya-hi-ye-hega

Ya-hi-ye-ne-he hega

Hega hega ya-hi-ye-hega

Ya-hi-ye-ne-he hega

Steady as the beating drum

Singing to the cedar flute

Seasons go and seasons come

Bring the corn and bear the fruit

By the waters sweet and clean

Where the mighty sturgeon lives

Plant the squash and reap the bean

All the earth our mother gives

O Great Spirit, hear our song

Help us keep the ancient ways

Keep the sacred fire strong

Walk in balance all our days

Seasons go and seasons come

Steady as the beating drum

Plum to seed to bud to plum

(Hega hega ya-hi-ye hega)

Steady as the beating drum

Hega hega ya-hi-ye-hega

Ya-hi-ye-ne-he hega

Savages

From Pocahontas

Music and Lyrics by Alan Menken and Stephen Schwartz

What can you expect

From filthy little heathens?

Their whole disgusting race is like a curse

Their skin’s a hellish red

They’re only good when dead

They’re vermin, as I said

And worse

They’re savages! Savages!

Barely even human

Savages! Savages!

Drive them from our shore!

They’re not like you and me

Which means they must be evil

We must sound the drums of war!

They’re savages! Savages!

Dirty redskin devils!

Now we sound the drums of war!

This is what we feared

The paleface is a demon

The only thing they feel at all is greed

Beneath that milky hide

There’s emptiness inside

I wonder if they even bleed

They’re savages! Savages!

Barely even human

Savages! Savages!

Killers at the core

They’re different from us

Which means they can’t be trusted

We must sound the drums of war

They’re savages! Savages!

First we deal with this one

Then we sound the drums of war

Savages! Savages!

Let’s go kill a few, men!

Savages! Savages!

Now it’s up to you, men!

Savages! Savages!

Barely even human!

Now we sound the drums of war!

Notes

1 Clements and Musker, 1992, Bonus Features, “Filmmakers’ Audio Commentary,” 0:05:13 ↩

2 “Grand narratives,” in Encyclopedia of Marxism: Glossary of Terms. Available: www.marxists.org/glossary/terms/g/r.htm. Access: 10 November 2005. ↩

3 Jean Baudrillard, “Disneyworld Company,” Event-Scenes (1996), available: http://www.ctheory.net/articles.aspx?id=158, access: 10 November 2005 ↩

4 Clements and Musker, 1992, “Filmmakers’ Audio Commentary.” ↩

5 op. cit., 0:33:44 ↩

6 op. cit., 0:53:30 ↩

7 Clements and Musker, 1992, 0:42:56 ↩

8 op. cit., 0:43:46 ↩

9 op. cit., 0:45:07 ↩

10 op. cit., 0:42:18 ↩

11 op. cit., 0:17:36 ↩

12 Clements and Musker, 1992, “Filmmakers’ Audio Commentary,” 0:03:02 – 0:03:20 ↩

13 “Al Hirschfeld.” Available: http://www.answers.com/topic/al-hirschfeld?gwp=19, Access: 5 November 2005. ↩

14 Clements and Musker, 1992, “Filmmakers’ Audio Commentary,” 0:07:06 ↩

15 Later on A Bug’s Life (1998, in co-operation with Pixar Animation Studios) and Dinosaur (2000) incorporated the same idea. ↩

16 Allers and Minkoff, 1994, 0:00:13 – 0:00:27 ↩

17 op. cit., 0:00:31 ↩

18 Cf. the lyrics of the “Circle of Life” in Appendix 1/2. ↩

19 Allers and Minkoff, op. cit., 0:09:35 ↩

20 Szőnyi, György Endre, “Az ezotéria diszkrét bája. Mágia és okkultizmus a kultúrtörténész szemével,” presented at Mindentudás Egyeteme – Szeged, 19 October 2005 ↩

21 It is also a way to fix the position of the audience in Western point-of-view. ↩

22 Gabriel and Goldberg, 1995, 0:15:49 ↩

23 op. cit., 0:16:05 ↩

24 Gabriel and Goldberg, 1995, Bonus Features, “Production,” 0:02:14 ↩

25 Gabriel and Goldberg, 1995, Bonus Features, “The Making of Pocahontas,” 0:12:56 ↩

26 Gabriel and Goldberg, op. cit., 0:27:59 ↩

27 cf. Said’s theory on Orientalism mentioned in part 1 ↩

28 Gabriel and Goldberg, 1995, Bonus features, Production, “Abandoned Concept: In the Middle of the River,” (Schwartz, 1993) ↩

29 Gabriel and Goldberg, op. cit., 1:10:03 ↩

30 With some relevance, the issue of scapegoating can be mentioned here. The British are involved in the war with the Native on the pretext of their captain’s captivity; the Natives, as Powhatans articulates it, were not in trouble had it not been for Pocahontas who deliberately disobeys and leaves the village. ↩

31 For the lyrics of “Savages,” see Appendix 1/3. ↩

32 Gabriel and Goldberg, op. cit., 1:01:18 ↩

33 op. cit., 1:01:22 ↩

34 op. cit., 1:01:38 ↩

35 op. cit., 1:02:16 ↩

36 Clements and Musker, op. cit., 1:17:42 ↩

37 Clements and Musker, op. cit., 1:04:57 ↩

38 op. cit., 1:22:08 ↩

39 Clements and Musker, op. cit. 0:00:16 – 0:00:29 ↩

40 op. cit., 0:00:33 ↩

41 For the lyrics of “Arabian Nights,” see Appendix 1/1. ↩

42 ibid. (emphasis mine) ↩

43 “Aladdin.” Available: http://www.answers.com/topic/aladdin-1992-film?gwp=19, Access: 5 November 2005. ↩

44 Clements and Musker, op. cit. 0:00:38 – 0:00:41 ↩

45 op. cit., 0:00:42 – 0:00:45 (emphasis mine) ↩

46 In primordial cultures, shamans were men who either were the eldest member in the community or had some kind of physical disorder. Rafiki has a similar disorder: he has a tail although mandrills do not have any. ↩

47 Allers and Minkoff, op. cit., 0:02:58 ↩

48 op. cit., 1:17:54 ↩

49 op. cit., 0:39:06 ↩

50 Allers and Minkoff, 1994, Bonus Features, “Filmmakers’ Audio Commentary,” 1:01:06 ↩

51 Allers and Minkoff, op. cit., 1:18:02 – 1:18:10 ↩

52 Allers and Minkoff, 1994, Bonus Features, “Filmmakers’ Audio Commentary,” 1:18:07 ↩

53 Allers and Minkoff, op. cit., 0:37:38 – 0:37:52 ↩

54 op. cit., 1:02:23 – 1:02:42 ↩

55 Allers and Minkoff, 1994, Bonus Features, “Orchestral Color,” 0:01:43 ↩

56 For the lyrics “Circle of Life,” see Appendix 1/2. ↩

57 Allers and Minkoff, 1994, Bonus Features, “Music: African Influence,” 0:00:22 ↩

58 Allers and Minkoff, 1994, Bonus Features, “Filmmakers’ Audio Commentary,” 0:01:33 ↩

59 Gabriel and Goldberg, op. cit., 0:55:14 ↩

60 For the lyrics of “The Virginia Company,” see Appendix 1/3. ↩

61 op. cit., 0:00:24 ↩

62 op. cit., 0:05:22 ↩

63 For the lyrics of “Steady as the Beating Drum,” see Appendix 1/3. ↩

64 op. cit., 0:06:35 ↩

65 op. cit., 0:06:23 ↩

Bibligoraphy

Primary sources

- Allers, Roger and Rob Minkoff dir. The Lion King. Written by Irene Mecchi, Jonathan Roberts and Linda Woolverton. Walt Disney Pictures, 1994.

- Clements, Ron and John Musker dir. Aladdin. Written by Roger Allens and Ron Clements. Walt Disney Pictures, 1992.

- Gabriel, Mike and Eric Goldberg dir. Pocahontas. Written by Carl Binder, Susannah Grant, Philip LaZebnik. Walt Disney Pictures, 1995.

Secondary sources

- Althusser, Louis. “Ideology and Ideological State Apparatus.” In Rivkin and Ryan eds., Literary Theory: An Anthology. Malden: Blackwell, 2004, 693-702.

- Anderson, Benedict. Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism. (Revised Edition.) London: Verso, 1991.

- Anzaldúa, Gloria. Borderlands/La Frontera. San Francisco: Aunt Lute Books, 1999.

- Ashcroft, Bill et al. The Empire Writes Back. Theory and Practice in Post-Colonial Literatures. Second Edition. London: Routledge, 2004.

- Bell, Elizabeth et al. From Mouse to Mermaid. The Politics of Film, Gender, and Culture. Indianapolis, Indiana: Indiana UP, 1995.

- Bernstein, Matthew and Gaylyn Studlar eds. Visions of the East: Orientalism in Film. New Brunswick, New Jersey: Rutgers UP, 1997.

- Bhabha, Homi K. “The Location of Culture.” In Rivkin and Ryan eds., Literary Theory: An Anthology. Malden: Blackwell Publishing Ltd, 1998, 940.

- Bordwell, David and Thompson, Kristin. Film Art: An Introduction. London: McGraw-Hill, 1997.

- Fanon, Frantz. Black Skin White Masks. London: Pluto Press, 1986.

- Hegel, G.W.F. “Dialectics.” In Rivkin and Ryan eds., Literary Theory: An Anthology. Malden: Blackwell Publishing Ltd, 2004, 647-692.

- Lyotard, Jean-François. “The Postmodern Condition.” In Rivkin and Ryan eds., Literary Theory: An Anthology. Malden: Blackwell Publishing Ltd, 2004, 355-364.

- Kaplan, E. Ann. Looking for the Other: Feminism, Film, and the Imperial Gaze. New York, New York: Routledge, 1997.

- Nadel, Alan. “A Whole New (Disney) World Order: Aladdin, Atomic Power, and the Muslim Middle East.” In Matthew Bernstein and Gaylyn Studlar eds. Visions of the East: Orientalism in Film. New Brunswick, New Jersey: Rutgers UP, 1997, 184-203.

- Rivkin, Julie and Micheal Ryan, eds. Literary Theory: An Anthology. Second Edition. Oxford: Blackwell, 2004.

- Rowe, John Carlos, ed. Post-Nationalist American Studies. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2000.

- Stam, Robert. Film Theory. An Introduction. Malden, Massachusetts: Blackwell, 2000.

- Said, Edward. “Orientalism.” In Julie Rivkin and Michael Ryan eds. Literary Theory: An Anthology. Second Edition. Oxford: Blackwell, 2004.

- Szőnyi, György Endre. “Az ezotéria diszkrét bája. Mágia és okkultizmus a kultúrtörténész szemével,.” Paper presented at Mindentudás Egyeteme, 19 October 2005

- Ward, Annalee R. Mouse Morality: The Rhetoric of Disney Animated Film. Austin, Texas: University of Texas Press, 2002.

- Žižek, Slavoj. Welcome to the Desert of the Real. London: Verso, 2002.

Internet sources

- “Aladdin.” In Answers.com. Available: http://www.answers.com/topic/aladdin-1992-film?gwp=19. Access: 5 November 2005.

- “Al Hirschfeld.” In Answers.com. Available: http://www.answers.com/topic/al-hirschfeld?gwp=19. Access: 5 November 2005.

- Baudrillard, Jean. “Disneyworld Company.” Event-Scenes (1996). Available: http://www.ctheory.net/articles.aspx?id=158. Access: 10 November 2005

- “Disney Lyrics.” Available: http://www.geocities.com/disneywonders/Lyrics.html. Access: 25 November 2006.

- “Full Cast and Crew for Aladdin (1992).” Available: http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0103639/fullcredits#writers. Access: 20 May 2006.

- “Full Cast and Crew for Pocahontas (1995).” Available: http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0114148/fullcredits#writers. Access: 20 May 2006.

- “Full Cast and Crews for The Lion King (1994).” Available: http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0110357/fullcredits#writers. Access: 20 May 2006.

- “Grand narratives.” In Encyclopedia of Marxism: Glossary of Terms. Available: “www.marxists.org/glossary/terms/g/r.htm:www.marxists.org/glossary/terms/g/r.htm. Access: 22 November 2005.

- “The Walt Disney Company.” Available: http://disney.go.com. Access: 25 December 2005.

Copyright (c) 2008 Nóra Borthaiser

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.