In this essay we discuss two cases of latent racial-ethnic resentment, one in Mexico and the other in the United States. They represent extreme cases where the ethnically dominant populations of two local communities directed their beliefs about inferiority and unworthiness, as well as their feelings of fear, anger and bitterness against members of new ethnic groups who came to live in their midst as immigrants: the Chinese in Cananea, in the northern state of Sonora, Mexico; and the Japanese in Salt Lake River, in the border state of Arizona in the United States. Accumulated negative ethnic perceptions and feelings in the specific context of historical circumstances in each place led to the total rejection of Asian minorities and the deterioration of inter-group relations in both communities, resulting in serious physical and political violence against these groups.

We will address the question of how the anti-Asian movement spread in the borderlands region. The extreme actions taken by Mexicans against Chinese immigrants occurred first in Sonora, and these served as a model for the Arizonans of Salt Lake River to follow against the Japanese who settled in their town. The agitation in opposition to the Chinese and Japanese presence was a transnational phenomenon. It proves that anti-Oriental racism, especially during the first decades of the 20th Century, was not distinctive to one nation or country. The fact that anti-immigrant resentment was a cross-border phenomenon shared by people of both nations means that racist-accepted ideology and hatred for non-European newcomers constituted a tendency that was strong enough to spread past national boundaries, irrespective of other historical, cultural, and political differences that distinguished each nation.

Cananea: Hub of the Anti-Chinese Movement in Sonora

Historians have generally agreed that Sonora—the only Mexican state to expel Chinese immigrants from its territory—was the hub of the anti-Chinese movement in Mexico during the early 1930s. The hatred of Chinese newcomers climaxed in the mining town of Cananea, located in the Arizpe district in the northeast corner of Sonora, close to the United States border.1 It was the strong popular hostility on the part of the white and mestizo residents of this town toward the Chinese group that encouraged the local and state politicians to take this racial resentment to a dangerous level, implementing and imposing extreme anti-Chinese legislation in advance of any other community across the state.

One of the most significant facts surrounding the case is that it was Cananea, the most ethnically diverse town in Sonora, which so strongly and specifically opposed this Chinese immigration. Considering that immigrants from the United States and Europe had settled in Cananea, drawn by its prosperous copper mine, there is no explanation for this historical reality of targeting only the Chinese newcomers, other than the history of widespread rejection of Asians in both the United States and Mexico. As in the United States, especially on the West Coast where throughout the 19th Century Chinese immigrants suffered the worst discrimination and legal exclusion, anti-Chinese reaction in northern Mexico during the early 20th Century was no different.2 It was part of the general resentment of Asian immigration in both sides of the border. Despite the urgent need for workers for employment in the numerous railway and mining projects, the established racial categories placed people of the Far East at the bottom. In comparison to the dominant population of European whites in the United States and Europeans and mestizos in Mexico, the Chinese were defined as an inferior race, and thus undesirable immigrants. Such pervasive and entrenched attitudes created an atmosphere charged with racist anti-Chinese sentiments in places where Chinese immigrants were concentrated, including Cananea.

Our research of documents in the Sonora archives and our investigation of both the town’s newspapers and diplomatic and military reports in the United States revealed new information about Cananea. The data is significantly helpful in providing a multifaceted interpretation of the anti-Chinese movement, which combines racial-ethnic, social class, labor, political, and diplomatic histories. First and foremost is the fact that Cananea was a company mining town, promoted by the Cananea Consolidated Copper Company, a corporation was owned by William C. Greene. An adventurous United States citizen, Greene managed to convert an “old Real de Minas” into a sophisticated and successful mining enterprise. As with other foreign nationals, the Americans and the Europeans who arrived in Cananea, the bonanza that Greene created also captured the attention of Chinese immigrants. Chinese male laborers began arriving in northern Mexico in the 1890s, an effect of the Exclusion Law that banned Chinese immigration to the United States in 1882. One third of them were concentrated in Sonora, but as one historian who studied Chinese immigrants in Northern Mexico explains, as a “prototypical company town,” by 1904 “it was in Cananea that the largest Chinese colony was found… It was exactly the kind of place that attracted Chinese immigrants: of the 1106 Chinese in Arizpe district, 800 resided in Cananea,” out of a total population of about four thousand people who lived in the entire state of Sonora.3

Even though it was rather pluralist ethnically, in comparison to other towns and cities, Cananea was no paradise of labor and ethnic relations. The company’s “dual pay scale by which foreign workers, principally skilled laborers from the United States, received much higher pay than Mexicans for the same work,” did not originate from Greene’s policy, but rather from the company’s compliance with the law. The law dictated a salary ceiling for Mexicans above which private enterprises could not legally rise. The system caused uncertainty and even chaos among Mexican workers, who showed discontent with their pay as well as with the labor conditions offered by the Cananea Consolidated Copper Company. Eventually, in 1906, the growing dissatisfaction brought about the bloody Cananea miners’ strike, which was crushed by Arizona rangers assisted by local Mexican troops.4

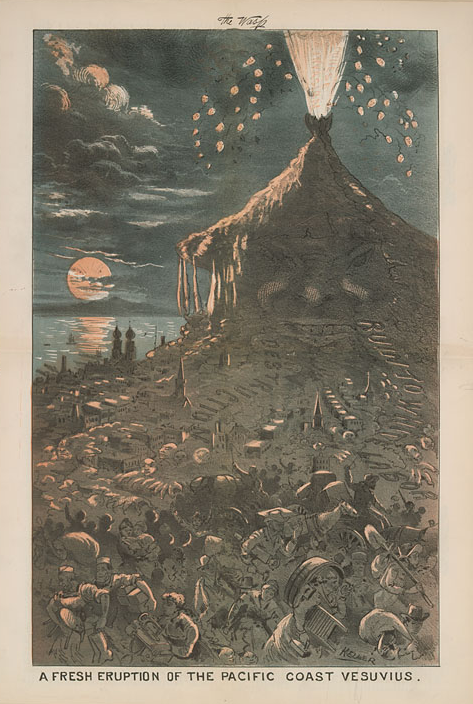

Should we conclude, therefore, that the anger manifested towards the Chinese by the Cananea workers originated merely from labor conditions in the mines? Our response to this question is no. There is evidence suggesting that the Sonorenses may have developed an early dislike for Chinese immigrants, taking after their neighbors in California. After all, Sonoran men were quite familiar with California, especially from the Gold Rush period in 1848 and 1849. Being experienced miners (some of them coming from as far south as the mining district of Alamos, Sonora), at the news of the discovery of gold, tens of thousands of Sonorans set out for California to try their luck in the territory that until just recently was their own, only to return soon afterward because of anti-Mexican harassment by “Yankees.” But when the quantities of gold no longer satisfied the Americans who had migrated in search of it, anti-foreign resentment turned against the Chinese, who were conspicuous for their different clothing, customs, and racial features.

Figure 1. “A Fresh Eruption of the Pacific Coast Vesuvius”

The Wasp (San Francisco), vol. 8, January-June 1882

The Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley

A generation or two later, the Sonorans reproduced what they had witnessed in California, which were negative attitudes and beliefs about the Chinese people: their alleged lack of morals on individual and collective levels, including indulgence, untidiness and lack of hygiene, opium consumption, polygamy, and concentration in overcrowded living spaces. In addition, anti-Chinese attitudes became part of escalating anti-foreign and anti-Chinese feelings as Mexican nationalism grew stronger at the end of the 19th Century, the early 20th Century, and during the Mexican Revolution starting in 1910. The ideal was to create a racially unified nation, known as La Raza (The Race), with an identity that was created in good part in opposition to the Asian ethnic difference.5 For example, during the Revolution, in 1911, revolutionaries killed nearly three hundred Chinese in the northern city of Torreón, Coahuila. And by 1916 Chinese immigration to Sonora was prohibited.6

Since the Chinese were excluded in Cananea, they themselves were reluctant to develop a strong sense of attachment to the town, as would generally be expected from workers in such a place. Typically, mining towns have been characterized by strong community roots and place identity generated by the sacrifices and hard living conditions of the miners and their families. In fact, only a few Chinese men worked in the mines as day laborers, and those who were employed by the mining company were unwilling to work in the dangerous underground areas of the mines, preferring instead lighter mining jobs. Furthermore, as they did in California, the Chinese of Cananea operated their traditional family laundries, and got themselves hired as cooks and servants in the homes of foreign families. Some of them also owned truck gardens, where they grew fruits and vegetables to sell locally. Thus their different occupations and their failure in the eyes of locals to commit to risky mining work made them appear even more as outsiders, unwilling to share the basic life experiences of the majority population.7

The social disapproval of the Chinese for adhering to their traditional ethnic occupations ran deep also because of the gender images associated with the occupations they undertook. In the harsh environment and risky work in the American West and the Mexican North, the gender set of beliefs idealized the masculinity associated with the tough achievement of conquering the frontier. In the European mind, the Chinese were commonly perceived as effeminate, delicate, and even cowardly people. Frontier folk, men and women alike, who romanticized courageous males, were repulsed by Chinese men because of their different appearance and short physical stature in comparison to the taller white men. But more significantly, in Western eyes, the Chinese male identity negated virtuous manliness because they confined their work to the protected family sphere of their own businesses, and above all, because of their employment as docile domestic servants. Oriental polygamy was also rejected as undignified. European men understood it as an indulgence to sexual relations and the abandonment of the male responsibilities of tough physical struggles and modern industrial labor. The implication of these views for the majority of the population was that the Chinese could contaminate the heroic frontier in particular and the nation in general.8

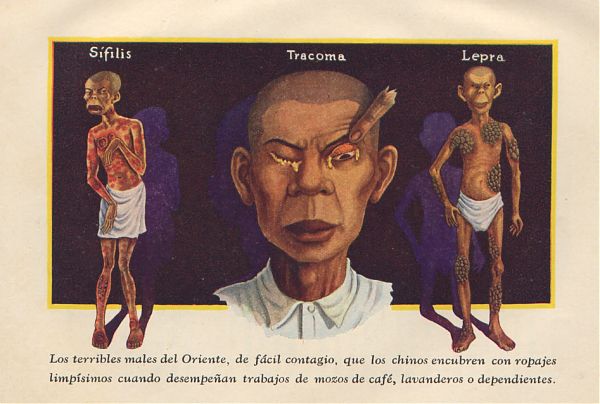

Within two years following the 1906 Cananea miners’ strike, the local weekly Gaceta de Cananea printed a series of articles criticizing the local Chinese community. The publication’s owner and editorialist Simón Montaño accused the Chinese residents not only of “killing” small businesses but also of lowering the Mexican workers’ wages. The Municipality of Cananea, Montaño assured his readers, was the Promised Land for the despised Chinese; they arrived in Cananea penniless like other immigrant newcomers, but “with their harmful pack of vices, of disgusting habits and everything else that this race has that is hateful and damaging, in order to create the largest colony that could ever exist in the country.”9 In their new environment, he wrote, the Chinese “race”—the term for non-European ethnicities at the time—lacked the notions of honor, morality, gentility, and “respect for authority and the Law.”10 The Chinese brought to Cananea what the majority of the town inhabitants considered “filthy habits,” “depraved vices,” and “inherently contagious and infectious diseases.”11

Figure 2. Cartoons Depicting Chinese Individuals as Carriers of Contagious Diseases

José Ángel Espinoza, El ejemplo de Sonora (Mexico: n.e., 1932).

Mexicans projected their disgust on the Chinese for unnatural body odor and perspiration, as if these traits were peculiar to the Chinese and did not apply to native Mexicans. This attitude became central to the growing popular anti-Chinese ideology in Mexico.12 In addition, their biggest evil, the Gaceta de Cananea argued, was vagrancy:

the great number of petty thieves… that roam around the streets helping themselves to the family holdings, businesses and all property they find on their way, to snatch a hen, a pig, some firewood, bottles, garments, and everything that is within the reach of so many petty thieves that no one can get rid of, because of their great numbers and because of the sagacity and boldness with which they commit their countless crimes.13

The anti-Chinese propaganda that the Gaceta de Cananea managed to spread during the late Porfiriato period just prior the Mexican Revolution had a strong impact on the residents of Cananea.14 This became particularly glaring after the Cananea Consolidated Copper Company was no longer able to absorb the surplus labor force that was continually arriving in the mining town. In 1908, a Gaceta de Cananea article warned:

We have neglected to warn the working classes from outside this city about the hardships they will face if, mislead by the rumors that circulate in places far away from this mining district, they resolve to embark on a trip believing they will find work any time they request it.

Nothing is further from the truth. The Cananea Consolidated Copper Company—from the moment the foundry began operating—has been hiring day by day the people it needs; but in such reduced measure that it does not amount to one tenth of the number of workers who arrive daily in Cananea from different parts of the country and from the neighboring territory of Arizona.15

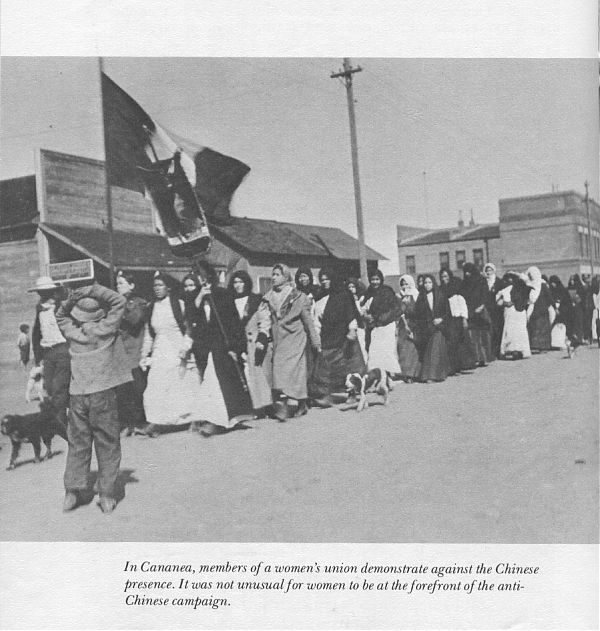

With unemployment becoming a constant problem in Cananea, Chinese men were blamed for decreased pay and, worse still, for displacing Mexican workers. This was particularly true during the violent and turbulent years of the Mexican Revolution. In February 1914, for instance, when the Cananea Consolidated Copper Company dismissed workers from its mines, the leaders of the Cananea Women’s Union exhorted the town’s Mexican residents against the Chinese. Working class women—who during the economic hardships of the revolutionary period desperately needed the laundry, cooking, and sewing jobs done by the Chinese—were especially susceptible to the anti-Chinese message:

A crowd of 500 heard speakers that demanded the forcible expulsion of the Chinese. Led by wives of mine laborers, the crowd began a rampage of destruction of Chinese stores in the immediate vicinity. While police watched, the mob robbed, stoned, and beat Chinese launderers. Deluged by protests, the mayor [of Cananea] and Governor [José María] Maytorena sent thirty mounted troops who dispersed the mob and arrested eight men. Charged with inciting the women to violence, the men spent one night in jail…. Gradually, order returned. Native hatred of foreign interests, especially Chinese…, continued.16

Anti-Chinese feelings and rhetoric, then, were not gender exclusive to men. They caught up with women as well, thus uniting the entire community around an aggressive anti-immigrant mind-set.

Figure 3. Women Protesting Against Chinese Presence in Cananea.

Evelyn Hu-DeHart, “Immigrants to a Developing Society. The Chinese in Northern Mexico, 1875-1932,” Journal of Arizona History 21 (Autumn, 1980): 49-86.

A further deterioration in the Mexican relationship with Chinese immigrants was marked in February 1916, when together with other merchants of the Sonora town of Magdalena, José María Arana, a small-time businessman and politician, created the Gran Asamblea Comercial y de Hombres de Negocios de Magdalena (The Great Commercial Assembly of Magdalena Businessmen).17 Its goal was to use “all legal means to eliminate the Asian merchant,” hoping, in the long run, to expel the Chinese from the state of Sonora once and for all (“de manera definitiva”).18 Indeed, it was not only the mine workers and their families in Cananea who resented the Chinese. The commercial and business competition that the Chinese presented caused the merchant middle-class to fear and dislike them as well. Surely, the issue was an ethnic matter, but since labor and economic relations played a central role in ethnic immigration, anti-Asian sentiments added yet another component to the already existing complexity of class relations.

Acknowledged as the “initiator and organizer of the first Anti-Chinese leagues” in Sonora, and aware that Cananea was the center of hatred toward the Chinese in the state, Arana began his campaign there. “It was no accident that he delivered his first address on the Chinese in Cananea,” claims one historian: “Long the center of a foreign population and a hotbed of xenophobia, Cananea was an ideal location to rouse the rabble against the Chinese.”19 Indeed, the presence of populist and chauvinist agitators in the town continued unabated. In 1917, Serapio Dávila, a schoolteacher and close associate of Arana talked to a crowd in the mining town. Significantly, he rationalized the anti-Chinese propaganda and action as justifiably legal by stating that it “‘did not go after ghosts’ but that it was rather motivated by the [revolutionary] 1917 Constitution.” Mexico’s Congress, he said, would soon dictate “the organic laws that will stop the yellow wave.”20

Towards the end of the decade, new legislation allowed the anti-Chinese movement to take such legal direction. Article 106 of the Ley del Trabajo y de la Previsión Social del Estado de Sonora (Law of Labor and Social Prevention of the State of Sonora), dated 31 March 1919, which originated from Article 123 of the Mexican Constitution, boldly stated: “The owners of every enterprise, workshop or commercial or manufacturing establishment have the obligation of hiring Mexicans for 80 per cent of their jobs.”21 Needless to say, this article targeted Chinese businesses that were traditionally run by Chinese and employed persons solely of their own ethnic group. The models for this policy were a series of ordinances enacted in California after 1852, which greatly limited work opportunities for the Chinese, and laws passed in the United States after 1875, forbidding the entry of Chinese laborers to the country.

While the Sonora authorities used the law to harass Chinese, the latter tried to defend themselves against attacks on their commercial and individual rights. The mayor of Cananea R. R. González wrote the following in a letter to Arana: “The Chinese who violate the Labor Laws, those I ordered to clean the public jail [sic], asked for relief, and the matter is being addressed. The general belief is that it will be granted.”22 Demonstrating his dislike for the Chinese, the mayor illegally forced those jailed to clean up the prison. Such abuse reflected that, out of sheer hatred, the town authorities permitted themselves to exceed the legal rules when out of public sight. Still, on their part, the Chinese displayed a capacity to fight back through legal means.

The decisive efforts to rid Cananea of Chinese residents did not stop with attempts to enforce the new law. For example, segregation of the Chinese became one of the residents’ goals. A slogan that repeatedly appeared in the Gaceta de Cananea urged the creation of Chinatowns outside the mining center: ¡¡El pueblo debe unirse y pedir se confine a los chinos, a un barrio apartado de la ciudad!! (The people must unite and ask that the Chinese be confined in a neighborhood separate from the city!).23 Not only did the anti-Chinese leader Arana support such a demand, but the government of Sonora also considered “the question of segregating Chinese,”…“wherever there is any [significant] number of them.”24 The idea, of course, echoed what Sonorans had witnessed in San Francisco, having that city’s Chinatown as model from their sojourn in California during mid-19th Century. Chinatowns also developed in other American cities, but contrary to what the Sonorans believed, this was not the result of white men wanting to separate the Chinese community’s homes and businesses and minimize their undesirable visibility in the cities. Rather, these Chinatowns developed out of Chinese tendency to concentrate in a single area for security reasons but also for their social and economic activities.25 In March 1919, Arana’s propaganda campaign achieved the passage of the state’s Organic Law of Internal Administration. Article 60 required that in order to maintain adequate hygiene and health, the municipal councils should move all houses and stores belonging to the Chinese to separate neighborhoods. In this way, Article 60 became a watershed in the crusade to reduce the Chinese presence across Sonora.26

Although the mayor of Cananea Julián S. González denied any support from the state government for his anti-Chinese actions, in reality he was assisted by the veiled approval of the Governor Adolfo de la Huerta, proving that the anti-Chinese movement extended beyond the reach of the locality and its authorities. At the very end of 1919, encouraged by the citizens of Cananea and apparently undeterred by the governor, González took an extreme and unlawful step: he set January 1, 1920, as the deadline after which Chinese residents were no longer allowed to remain in the town itself.27 “A person arriving last night from Cananea,” the United States Consul Francis J. Dyer wrote from Nogales, Sonora,

has informed us that the Presidente Municipal (Mayor) of that important mining region has notified all of the Chinese living there that they must leave that place for other parts of the State before the end of the present year. It seems that the said Presidente is basing his action on the fact that the Mongolians [sic] have completely monopolized the business, not leaving anything for the Mexicans, and further because the people have laid their case before the Governor of the State.28

“There have been several public anti-Chinese demonstrations here and public anti-Chinese speeches in the last few days,” also reported J. M. Gibbs, the United States Consular Agent at Cananea. Prior to leaving Cananea, the Chinese merchants were forced to close down their stores, thus leaving their property obviously unprotected. According to Consul Dyer, “several anti-Chinese demonstrations occurred [in Cananea] breaking windows and throwing stones.”29 As to the increased number of soldiers in a local garrison required to handle the disorder, Consular Agent Gibbs informed: “I am advised that we have at the present time 70 soldiers in Cananea. I am also advised that there are expected at Cananea in the next few days some 150 men to increase the garrison here temporarily.”30

In spite of the street violence and pressure by the local authorities on Chinese store owners, Governor De la Huerta informed the United States consul that after the involved Chinese proprietors achieved protection through habeas corpus (amparo), the closed shops were subsequently “reopened under an injunction and are currently doing business.”31 This was proof that some Chinese learned the hard way about how to defend themselves from the abusive local and state authorities. But if some were willing to look after themselves through the legal system, other Chinese gave up hope altogether. As Consular Agent Gibbs put it:

Most of the Chinese stores are open now and doing business without being molested, with the exception of a few who became so frightened that they closed out their stores and have left Cananea. I believe that several of the Chinese will make arrangements to close their business here as they feel that they will be molested in so many different ways that it will not pay them to continue.32

Harassment of Chinese indeed increased more in Cananea than anywhere else in Sonora during the following years. Yet most Chinese residents were able to cope with the persecution for the remaining part of the 1920s, until the moment when they had no choice but depart. In 1921 Mexico prohibited most Chinese immigration: laborers were not allowed entry, while only those with capital to purchase land for farming were permitted to enter the country. There was a period of escalating anti-foreigner attitudes in the United States as well, fed by economic anxiety, political fears of communism, notions about race, and suspicions of a growing cultural diversity. These xenophobic sentiments eventually culminated in the Johnson Immigration Act of 1924, which provided the basis for closing the gates of the United States to immigrants.33

In Mexico, in 1925, the Liga Nacionalista Pro-Raza (Nationalist Pro-Race League) was founded in Hermosillo, the capital of Sonora, signaling the 1930s as a period of an even stronger anti-Chinese movement and emphasized Mexican nationalism.34 Echoing the fascist and Nazi racial theories and exclusionism, which spread from Europe to Mexico and Latin America, in 1930 the Liga Nacional Anti-china y anti-judía (The Anti-Chinese and Anti-Jewish National League) was organized. It reminded the Mexicans of their “obligation to avoid racial degeneration.”35 Furthermore, the arrival in Mexico of the Great Depression provided additional fuel to the anti-Chinese movement, as many Mexican laborers previously employed in the United States were forced to return to Mexico.36 The authorities of Sonora, where the largest number of Chinese in Mexico lived, once again pressed their case against them. The ligas antichinas (Anti-Chinese Leagues) terrorized the Chinese, claiming that they took precious jobs away from Mexican nationals. The Chinese requests for defense from sympathetic Mexicans and Americans were of no avail. It was in this atmosphere that Sonora’s anti-Chinese movement grew with such force that its politicians finally settled on the policy of deportation. In August 1931, the Chinese themselves decided to leave the state. Following orders from Rodolfo Calles—the new governor of Sonora and son of the former president of Mexico Plutarco Elías Calles—many Chinese were transported in trucks across the United States border to Arizona.37 Coronel Robert S. Knox of the United States Intelligence Office in Nogales, Arizona, reported in February 1932 on the mass expulsion:

The continuing deportation of Chinese from the state of Sonora and the fear of being arrested and jailed has caused additional consternation among the dwindling ranks of Asians. From a population that numbered approximately 3000 Chinese the previous fall, there are now fewer than 1000 according to a public statement made yesterday by Yao-Halang Pong, Chinese consul in Nogales, Sonora.38

The state and local governments definitely had gone to extremes to underscore their decision to expel all Chinese from Sonora. More severe, however, were the steps taken by the authorities in Cananea and Nogales, two border towns in Sonora:

Ack Wong, Chinese vice-consul, was jailed and kept isolated in Cananea and it was only when his jailer fell asleep and he was able to communicate by telephone with the American consular agent that he was freed. In Nogales many were told that the military authority wanted to see them, and when they arrived at his office, they were forced on a train and sent south. Last night 46 crossed the border towards the United States in Nogales. The total number of Chinese waiting to be deported in Nogales, Arizona, is 181.39

Yet, while the leaders and residents of Cananea went far in their actions against the Chinese, the town was not necessarily the only locality where the movement flourished. Laws to limit the number of Chinese workers in their own businesses, to create Chinatowns, and a 1923 law that prohibited marriages between Mexican women and Chinese men were indeed first tested in Cananea, but the excessive measures Mexicans in this town were willing to support were later put in effect in other places.40 The Chinese learned to stand up for their rights legally, and their patience in dealing with social animosity continued largely undiminished for many years. But it was the intolerance that was defended (and in some cases pursued) by the authorities that finally broke them. The eventual expulsion of more than 3500 Chinese from Sonora put an end to the Chinese presence in the state. The destruction of Chinese commercial establishments brought about economic difficulties in the state, until native Mexicans took over the business economy. The Chinese who fled to neighboring Mexican states such as Sinaloa, Chihuahua, and Baja California Norte (and to a lesser extent to the border city of Mexicali)—where an anti-Chinese Nationalist Party was organized—were unwelcome in those places as well.41 “_El ejemplo de Sonora_” (The example of Sonora) of mass removal was not repeated.42 However, it undoubtedly influenced the Arizonan neighbors across the national border, who attempted to take a similar route. But, their efforts, on the other hand, were to rid themselves of the Japanese population in their territory.

The Anti-Japanese Movement in Salt Lake River, Arizona

Prior to 1934 and the emergence of the anti-Japanese movement in Salt Lake River, Arizona, Arizonans had spent a several years witnessing how sentiments of hatred were expressed towards the Chinese in neighboring Sonora, particularly in Cananea, and how the authorities there had succeeded in their expulsion and removal operation. In addition to the anti-Chinese “Sonora example,” anti-Japanese tendencies that had been brewing for some time in California also influenced the southwestern United States, including Arizona.

After more than a decade of labor immigration from Japan and Hawaii into the United States and especially California, white supremacists and labor unions in the state demanded that admission of Japanese people into the United States be stopped. The “Gentlemen’s Agreement” of 1907 between the two countries pledged to prohibit further emigration to the United States.”43 In itself, the agreement did not settle the problem, given that the Japanese population increased. While labor unions vehemently opposed their presence in the country, “Japanese laborers kept dribbling in from Japan, despite the limitation that the Japanese government had imposed.”44 The Asiatic Exclusion League, which “considered the Japanese already on the Pacific Coast a ‘menace’ to American life,” started its campaign to exclude Japanese and Koreans from the country as early as 1905. In February 1908, the California state legislature was bent on “making conditions so disagreeable for the Japanese that they would ‘voluntarily’ leave,” as well as making it difficult for them to settle in the state.45

As in other places in the Americas where the Japanese were immigrating, such as Brazil, Peru, and Colombia, Californians most disliked the fact that the Japanese were leasing the richest farmlands.46 They successfully grew produce on their farms and sold it in major urban centers, thus triggering the envy and resentment of whites. The fear of Asian success and competition from Japanese farmers brought about a crucial discriminatory law against the California Japanese in 1913: the First Land Law. Its purpose was to prevent and reduce the Japanese farmers’ agricultural prosperity by hindering their opportunities to own and rent land. The law disallowed citizens of Japan to purchase land, lease agricultural land, act as guardian for a native-born minor if his estate consisted of property that the Japanese could not legally hold, or transfer property with intent to evade the law. Subsequent to California, Arizona’s legislature also passed an Alien Land Law in 1913, and in 1921 it expanded the law to make agricultural business even harder for alien Arizonans of Japanese descent.47

In 1922—against the backdrop of the anti-foreign atmosphere of the early 1920s—the United States Supreme Court also resolved “that Japanese were outside the zone of those who could become naturalized.”48 Long after the 1882 Exclusion Law against the entry to the United States of Chinese, whose arrival had begun earlier, the Johnson Immigration Act of 1924 denied a quota to aliens ineligible for citizenship and banned the entry of new Japanese immigrants. In response to the widespread exclusionist belief that such groups did not fit within the American national collective, the makers of the law sought to minimize the flow of immigration by many national groups into the country. At the same time, the law represented a victory for the anti-Japanese movement in particular.49

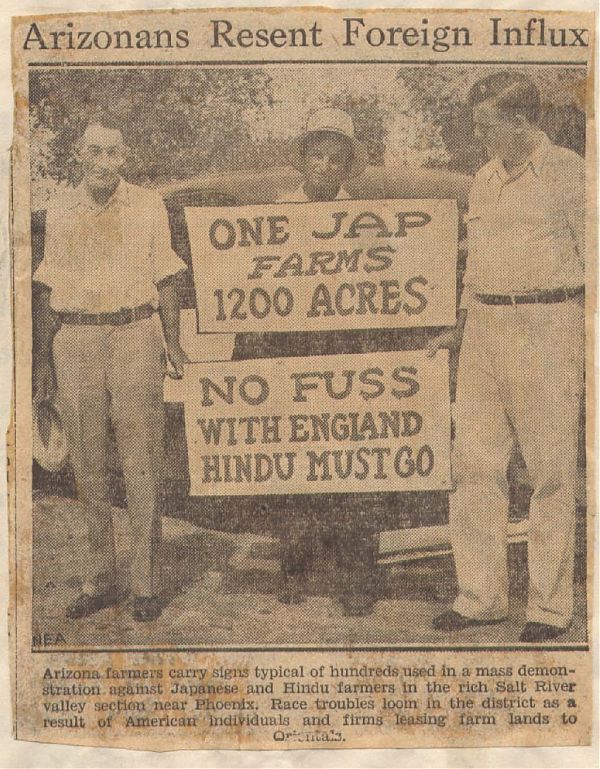

The anti-Japanese hostility that first centered in California gradually spread to other regions, including Arizona, during the first three decades of the 20th Century. The increase of anti-Japanese sentiment can be explained by their agricultural expansion in the Salt River Valley and the exclusion of Chinese immigrant workers in 1882, which also attracted Mexican migrants from southern Arizona and Sonora to settle in Salt River Valley.50 The first hundred Japanese contract laborers appeared in Arizona in the late 1890s. In 1905 a slightly larger group arrived in Salt River Valley, Maricopa County, in central Arizona, where by 1920 they had created a stable independent farming community known for the quality and quantity of their vegetable crops.51 White farmers resented Japanese farmers for their thriving truck farming, and accused them of unfair labor practices, employing their women and children and taking the best farmland in the region. Mexicans received the most marginal land, as well as discriminated against and segregated. However, the anger of local farmers was not directed towards them but, more precisely, against the Japanese “colony.” Fear of its expansion grew, and the complaints of white farmers motivated the county authorities to enforce the 1913 Land Law. Nevertheless, the Japanese became skilled in evading some of its restrictions, and by 1930 their number in Arizona was still growing.52

As with the Chinese immigrants in Sonora, and motivated by a similar argument of economic competition over jobs and commerce with the onset of the Great Depression, the Japanese in central Arizona were also blamed for widespread unemployment, reduced prices of farm produce, and other economic evils.53 The discovery that Japanese farmers were able to successfully live off the produce they grew on the land they cultivated served to fuel the ever building anger of their white Salt River Valley neighbors.

Anti-Japanese hysteria was further nurtured by local rumors in the summer of 1934 that a vast number of Japanese were planning to move to Arizona from Imperial Valley, California, thus adding more Japanese people to the existing population of Asian families.54 “Unofficially,” the central Arizona newspaper Douglas Daily Dispatch wrote,

[I]t was estimated that the Japanese population of Arizona, up to the time of the present trouble, might have been 1000. Ranchers of the Fowler district, however, have charged there has been an influx of Japanese recently from California, and that the Japanese population in that area alone has been augmented greatly. Japanese association officials have denied there have been any additions to the state’s population of Japanese.”55

In an attempt to reconcile with the local farmers, the Japanese Association of Arizona, together with the Japanese consulate in Los Angeles and the city’s Japanese American Citizens League (JACL), proposed to help return newcomers to California. The Japanese Foreign Office interfered as well, and the dialog between the two countries lasted for two months.56

Not only did the local white ranchers view with displeasure an increasing number of Japanese immigrants in their midst and the continuing success of the local Japanese despite the depression, but they also felt a new and critical competitive threat at the very time when the Great Depression was especially bad. In 1934—two years after the Sonorans had managed to banish the Chinese from their state— farmers in the Phoenix area, with a similar goal in mind, organized an association that they called “The Farmers’ Anti-Oriental Society.”57 Claiming that the Japanese farmers of the valley took over lands by conspiracy, the Anti-Oriental Society declared their presence as illegitimate. In a move similar to what Sonora’s Mexican natives had done in 1932, giving the Chinese very short notice before expelling them, the Phoenix farmers gave the Japanese only ten days warning that they would be forced to leave by August 25, 1934. The decision to drive them out was declared on August 17 in a parade of 150 cars organized by the anti-Japanese organization, “following a meeting attended by more than 600 white farmers.” If the ultimatum “is not obeyed, the farmers declared, steps will be taken to enforce it.”58 At this point, the United States federal government began to worry about the events in Arizona. Acting Secretary of State William Phillips was concerned that conditions in Salt River Valley might deteriorate into instability and violent behavior; the reports he had received informed him that a local league of farmers there had “resolved that all Japanese in the valley be removed and their lease contracts be canceled.” Phillips recognized that any “use of force may lead to resistance by the Japanese and result in acts of violence.” Above all, the concern revolved around possible “difficulties in the relations between the United States and Japan and the nationals of each in the territories of the other.”59

Under these circumstances, the Acting Secretary of State told the governor of Arizona Benjamin Baker Moeur that he hoped such a “critical situation” would be prevented. Nevertheless, although the Local County Attorney’s office promised that “the farmers of this valley protesting Japanese situation will not resort to physical violence,” and despite the declaration by the Governor that he felt “sure that the common sense of the citizens of Arizona will prevent violence of any kind,” no one could guarantee that violence might be practically prevented.60 Trying to absolve himself of any internal political responsibility, the governor published in the local press the telegram he received from Acting Secretary of State Phillips. Immediately following this, Phillips received a cable from the secretary of the Anti-Alien Association Committee, which clearly reflected the farmers’ conspiracy thinking, typical of anti-Asian and anti-immigrant xenophobia:

Having read your telegram to the Governor of our State in our local newspaper we take exception to the attitude you have shown in championing the cause of the alien Japanese without hearing the side of your own American citizens. We American farmers of the Salt River Valley contend that these Japanese aliens are breaking the laws of our state through conspiracy to obtain farmland. Inasmuch as we have suffered through this practice for a number of years we are determined to protect our homes and livelihood from the law-breaking alien. We claim that the Japanese residents of this valley are an organized bunch of criminals as they have thoughtlessly conspired to break our state laws year after year over a long period causing the small American farmer, the real pioneers who brought this valley out of the desert, great suffering and economic ruin.61

Moreover, the telegram stressed that it was the Japanese presence and unfair economic competition that forced the Arizona farmers to accept the economic relief coming from the United States government during that period.

Many of our American Salt River Valley farmers have been compelled to accept our Government relief caused by unfair competition by those aliens as they have a system of massed [sic] production of the commodities adapted to grow in this climate that has been demoralizing the markets to the extent that we American farmers cannot survive and all of these activities on the part of the aliens have been accomplished through conspiracy and evasion of the laws of our State, we have repeatedly appealed to our State and county officials to hold us without success until in desperation we finally [were] compelled to organize for our own self-preservation.62

The Anti-Alien Association Committee’s secretary also suggested that the Japanese were “bad Americans” who could not possibly be part of the beautiful America that belonged to whites. In his view they had “cast their eye on this valley and their population here has been steadily increasing for fifteen years. Having seen this beautiful valley developed from a desert to a garden, we wish to live here and raise our families in peace with good Americans for neighbors.”63 Aware that the federal government wished to prevent violent disorder, the secretary assured that the members of the Committee would “use every possible precaution to avoid violence.” At the same time, however, he wanted the authorities to know that his Committee had fair reason to protest against “this bunch of law breakers being championed by our Government when we feel that we are the injured parties.”64

Although the Arizona state government had pretended to conduct a study of the occupation of land in Salt River Valley, white farmers knew that the Arizona Alien Land Law of 1933, which forbade aliens land ownership, had not been enforced in practice.65 At the end of August, a delegation of farmers complained to the governor about what they perceived as a failure of the Maricopa County Attorney’s Office to implement the law. Governor Moeur assured his guests that if the county failed to take “proper action, he would ask the state’s attorney general to ‘take a whirl at it’.”66 On the other hand, toward the end of September a delegation from the Arizona Japanese Association also met with Moeur. His promise to them was not what the white farmers would have liked to hear: that the state would employ the National Guard, if necessary, to protect Japanese lives and property.67 And since Moeur’s government did not satisfy the white farmers, the situation worsened. Constant communications flowed among the federal administration and state authorities, whose officials were politically anxious about the impact of the issue on the eve of the upcoming primary elections in September.68

Most importantly, the diplomatic representatives of Japan in the United States were involved, as well, in the intensive exchange of information. While the Department of State wanted to avoid at all costs violent confrontations between Japanese and whites in Arizona, the farmers worried about a new influx of Japanese migrants arriving from California. And since the farmers’ perception was that the government had betrayed them, they were preparing “to take matters into their own hands.”69

Figure 4 “Arizonans Resent Foreign Influx”

Douglas Daily Dispatch, September 4, 1934

On September 14, 1934, the first of several reported assaults against Salt River Valley Japanese farmers took place. The attacks were directed against Japanese property, not against the owners. Nevertheless, the state authorities made no arrests and did little to identify the attacking bands beyond branding them as “night riders.”

George Todano [sic], Japanese farmer, reported to the sheriff’s office here six masked men fired two shots at his truck early today and then pushed the machine into an irrigation canal.

Tadano [sic] said he was sleeping in a field near his truck and was awakened by the gunfire. He said he saw the men in the act of pushing the truck into the canal. He called to them, he said, and they scrambled into a waiting car and drove away.70

This assault was not an isolated case. Other severe acts of violence took place six days later when unidentified persons blew up three dams on three Japanese farms. According to the editorial in the Douglas Daily Dispatch,

The dynamite blasts, which caused no major damage [sic], all occurred within a period of about two hours shortly after last midnight at widely separated points in the valley.

The Maricopa county sheriff’s office, which is conducting a searching investigation, said apparently the dynamite had been placed in cans and hurled from an automobile in at least two instances. In the third, where a floodgate was blown up and 20 acres of land inundated, officers said, the dynamite may have been planted and set off with a time fuse.

On farms operated by Fred Okuma and R. Asano, the explosions occurred between 80 and 100 feet from their dwellings. At the R. Sugino home an object was hurled against the house by the force of the explosion… doing slight damage to the roof and a window screen.71

Alarmed by the information arriving in California from Arizona, the Los Angeles Times stated in its editorial that “Governor Moeur and other State and local officials of Arizona owe it to their State to see that there is no recurrence of the bombing by night-riders of Salt River Valley to ranchers of the Japanese race, and that prompt justice is meted out to the perpetrators of this campaign of terror… The laws of the State must be upheld.”72 In view of the situation, by early September the Japanese consulate in Los Angeles had already rushed vice consul Shintaro Fukushima to Salt River Valley in order to defend some of the Japanese who were American citizens by birth and owned and leased land legally. The governor kept claiming: “I want to enforce the law not with an iron hand but gently, as I feel there is an equitable way of adjusting this situation without trouble.”73

On a higher diplomatic level, in a letter to Secretary of State Cordell Hull, the Japanese embassy’s Chargé d’Affairs requested from the United States government a prompt solution to the Salt River Valley crisis. Hull, in turn, asked the governor to stop the acts of violence against Japanese citizens. While state politicians attempted to pacify the local farmers, Governor Moeur denied to Hull the seriousness of the situation: “The two incidents referred to [me] by the Japanese embassy… were more than likely attributable [sic] to Communistic or ‘Red’ activities in the Salt River Valley at this time.”74 Whether “red” agitators—commonly blamed in the 1920s and the 1930s by right-wingers, conservatives, and anticommunists—or simply “night riders” were responsible for the attacks, it became evident that the governor was not doing much to stop the perpetrators. White farmers took this as a sign of toleration of their activities. Noting this, the Japanese consul in Los Angeles, T. Hori, declared to the Governor of Arizona that “despite my repeated appeal and your assurance”…“bombing again occurred last night causing damages and injuring an innocent child asleep. This is the seventh of similar [acts of violence] occurring within the past six weeks and as far as I know no suspect was apprehended.”75 A superintendent of the Methodist Episcopal Church who worked among the Japanese also attested to the continuing “incidents”:

The first word to reach my ears was that there had been another raid by bombers on the night of October 29. In this case the aim of the night-riders was somewhat better than on the previous occasion at the house of a certain Shibata, the windows were broken and the child sleeping quietly in its bed was considerably cut by the falling glass. A bomb was also exploded in the yard of a certain Taki Guchi. No one was injured, but the family was badly frightened, and the Mrs. Taki Guchi, who was pregnant was dangerously excited.”76

At the same time, in a letter to the Phoenix Gazette white farmers continued attacking the Japanese farmers through a rhetorical technique that extolled their own historical suffering, venerable heritage, belonging, and patriotism.

The farmers of the Salt River Valley are a long suffering people, willing to suffer great amount of injustice rather than to offer a resistance, but when their homes are being taken away from them, they are deprived of the right to make a living for their children and their children are deprived of the wonderful heritage that our pioneer fathers wrested for us from the desert wastes, it is time for us to assert our rights. Though the farmers be slow to anger, once aroused, they prove a foeman worth of their steel [sic].77

While stressing their victimization as citizens, they insisted on their rightfulness to exclude Japanese from their deeply rooted community and from the United States in general:

The Japanese dodger sought to create in the minds of the people of the community that they were a patriotic, law-abiding group of citizens whereas in fact they are a group of alien-Asiatics who cannot become citizens of the United States and who have no interest in the United States other than the money which they can take out of the United States, not a small part of which is in violation of the law.78

During the following months, both verbal abuse and physical violence against the Japanese of Salt River Valley basically continued. By the end of 1934 it was evident that the situation there was not merely a local affair, but that it also had triggered an international conflict between the United States and Japan. As Japan was asserting itself as a world power and insisting on its obligation to protect its immigrant citizens, its diplomats were pressuring the State Department to insist on the governor’s collaboration.79 Acting Secretary of State Phillips designed a two-pronged plan. First, he tried to present the anti-Japanese sentiment in Arizona to the Tokyo government as part of a broader xenophobic tendency equally directed against Hindus and Mexicans in the state, and “all alien elements whose mode of living and economic activity conflict with certain native American elements.”80 Second, Phillips planned to pressure Governor Moeur to halt to the new anti-Japanese legislation, “the most drastic anti-Japanese laws ever proposed in America.” Even the New York Times described the House Bill 78 as “stiff”:

The anti-Japanese bill allows all aliens to “occupy, use, cultivate and transfer real property only to the extent and for the purpose prescribed by any treaty existing between the United States and the nation of which such alien is a citizen and subject and not otherwise.” Japanese are not eligible as American citizens and would be excluded from agricultural activities. The bill further forbids an alien from leasing or handling land through another person legally eligible, a practice which valley farmers claim has been prevalent. Any crops grown in violation of the law are subject to confiscation and become the property of the State without regard to any prior mortgage or lien except that which might be held by the United States Government.81

The Acting Secretary of State Phillips understood that he could press Governor Moeur because he was “reluctant to commit Arizona to any policy strenuously disapproved at Washington.”82 Phillips questioned Moeur about the constitutionality of the bill and asked him to kill it. Passing such a bill in Arizona, warned Phillips, would have serious repercussions in California and other states.83 Through the Arizona District Attorney, the acting Secretary of State was finally able to influence the state legislature.84

The issue involving the relationship between Japan and the United States was indeed delicate. Whereas the governor of Arizona supported an anti-Japanese bill in an attempt to calm his constituents, the acting Secretary of State, pressed by Japanese diplomats, was forced to unofficially interfere in Arizona’s internal politics. Because Phillips wished to avoid meddling directly (or at least openly) in Arizona politics, he unofficially recruited the United States Attorney in Phoenix. Clifton Mathews was more than willing to oblige. Through him, the Acting Secretary of State hoped to make Moeur comprehend the potentially dangerous diplomatic implications of his attitude. Mathew visited Moeur, and reported the following to the Department of Justice:

Without mentioning that conversation [we held together] or quoting any one in Washington, I pointed out the objectionable features of the proposed legislation. I believe the Governor understands the situation and will do the right thing.85

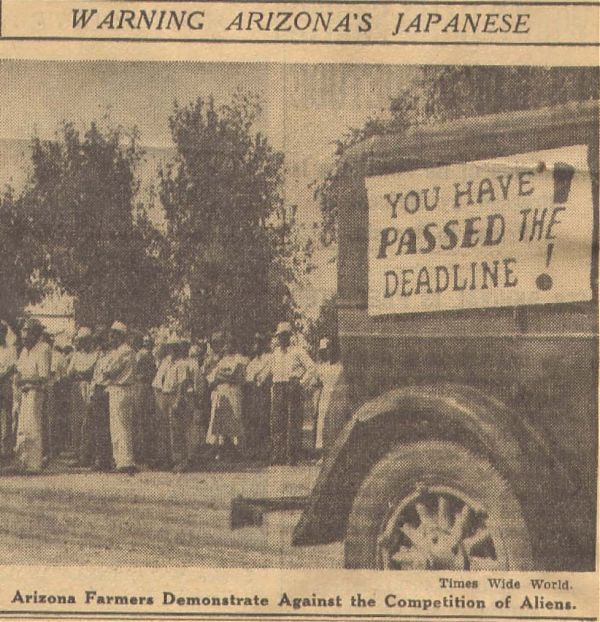

Figure 5 “Warning Arizona’s Japanese”

The New York Times, February 17, 1935

As a result of his talks with Clifton Mathews, the governor did “the right thing” by delaying the passing of the bill. The Arizona white farmers, who had expected the legislature to respect their wishes, learned from the Douglas Daily Dispatch about the possibility that the bill might not pass because of “the great press of legislation remaining… in the final three days of their regular session.”86 Indirect pressure from Washington, then, did have an effect on the governor. In his state, and for the benefit of the white farmers on whom he depended politically, Moeur skillfully fashioned the notion that he advocated anti-Japanese legislation while at the same time abiding by Washington’s demands. Because he stressed that the only problem was the short margin of time left for the legislature to approve the bill, white farmers did not doubt his sympathy. The Dispatch was instrumental in helping the governor present the time issue as an obstacle:

The statutory session of the Arizona legislature ended at midnight but a congestion of bills and a deadlock between the houses has kept the lawmakers working overtime. It was generally expected their session will end tomorrow leaving the alien bill and others to die on the calendar.87

The killing of the House Bill 78 in March 1935 marked the end of anti-Japanese terrorism and harassment in Salt River Valley. The Anti-Japanese movement and racial animosity continued, but the threats, demonstrations, occasional violence, and political pressure failed to chase the majority of the Japanese out of Salt River Valley. Some, however, did leave, mostly for California. Statistically, during the 1930s, the Japanese population of Arizona decreased by 30 per cent, a fact demonstrating that a strong racist sentiment prevailed. Most probably, without the Japanese government’s intervention and the pressures on Arizona officials, the Japanese of the Salt River Valley would have suffered considerably more than they did, and their number in the state would have dwindled even further.88

Conclusion

There is little doubt that, while the “Sonora example”—that is, the way in which this Mexican state managed to expel most of the Chinese residents from its territory—did not have any major resonance or influence in other Mexican states, it did impact Arizonan white farmers. They followed the events in Sonora with interest and attempted to apply the “Sonora example” in their state as a useful model to drive out their Japanese population. Fueled basically by ideas about inferior races, the anti-Japanese crusade in Arizona was ignited by the rapid deterioration of economic conditions, and it turned racial resentment into racist political activism and violence.

It has been said that the extreme violence in Sonora included massive killings of Chinese on their way to the border on what was called the “path of death.”89 In Arizona, by comparison, violence mainly involved the destruction of Japanese property and farming infrastructure. Another significant difference between Cananea and Salt River Valley was that the anti-Chinese campaign in Mexico was supported by the state and national governments, whereas in Arizona—after a stretch of empathy with the white farmers—neither the state nor the federal government were able to back the anti-Japanese movement. Unlike the case in Mexico, whose government paid little respect to Chinese diplomats, in the United States the State Department yielded to Japanese diplomatic pressure.

The brutal xenophobic actions taken by Sonoran miners and Arizonan farmers did not last for long. With the consent of the federal government, state officials in Sonora managed to expel the great majority of Chinese from their state and the crisis simply ended in this major aggressive manner. In Arizona, on the other hand, the anti-Japanese crusade was stopped short by the political institutions and machinations that brought to an end the idea of physically removing the Japanese farmers from their Arizonan lands.

The chronological and geographical proximity of the two anti-Oriental campaigns demonstrate the rapid spread of attitudes and actions, capable of crossing borders despite fences and border patrols. The period’s racism and resentment of Oriental immigrants were shared by the majority of mestizo communities in Sonora and by European white Americans in Arizona. The revulsion and fear of Orientals, depriving them of citizenship rights and treating them violently on both sides of the border proved to be part of a broader trend. The Chinese and Japanese—to mention only two Asian groups—were unlike white European immigrants who were not explicitly excluded as immigrants and citizens. The Chinese and Japanese arrived in the New World and, in this case, moved back and forth between the United States and Mexico precisely because they were refused the citizenship that other immigrant groups eventually received. They had difficulties establishing roots in places where they settled because they constantly faced rejection and abuse by the majority population when they dared to call these places home.90 As hated aliens without citizen’s rights, their fate in the Americas was to be a displaced people.

As a social and cultural phenomenon, the anti-Asian mindset was not solely associated with Mexicans or with mainstream white-Americans. It was widespread across northwestern Mexico and the southwestern and Pacific United States, constituting a significant and broad “frontier phenomenon.” Moreover, it was not a phenomenon unique only to the American frontiers; it was known also in the new colonial societies built by Europeans who tried to reinforce “white nationalism.” Australia, for example, also created the Immigration Restriction Act in 1901, banning non-white immigration to exclude people of any “Asiatic race,” while at the same time separating its own Aboriginals from the nation.91

Despite some differences in the methods of anti-Oriental abuses between northwestern Mestizo-Hispanic Mexico and White-Anglo southwestern United States, the history shows that in regard to racism and xenophobic nationalism, the traditional national divide is invalid. Chinese and Japanese immigrants who contributed to the economy and development of those regions were historically linked through a similar economy, the same Hispanic ethnicity, ethnic diversity, and the exchanges of political ideas.92 In addition, Asian groups were interconnected cross-border by family and ethnic ties through migrations between the Mexican and United States frontiers. Yet in the process of nation building in these regions, westerner pioneers saw themselves as “guardians of the imperiled frontier of white civilization.”93 Both countries sought to create their separate national and regional identities through the exclusion and persecution of ethnic and racially different groups, including blacks and native-Americans in the United States and indigenous peoples in Mexico. Politically, two national states indeed developed, but culturally and socially the large borderland region was united cross-nationally through a destructive history of anti-Chinese and Anti-Japanese rejection.

Notes

1 Evelyn Hu-DeHart, “Sonora: Indian and Immigrants on a Developing Frontier,” in Other Mexicos: Essays on Regional Mexican History, 1876-1911, edited by Thomas Benjamin and William McNellie, 177-211 (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1984). ↩

2 On the anti-Oriental movement in the United States at the early 20th Century, see John P. Young, “The Support of the Anti-Oriental Movement,” Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 34.2 (September, 1909): 11-18; Suchang Chan, Entry Denied: Exclusion and the Chinese Community in America, 1882-1943 (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1991). On Chinese immigration to Latin America, see Ronny Hurtado “Los chinos en Hispanoamérica,” Revista de Historia de América 134 (January, 2004): 219-226. ↩

3 Juan Luis Sariego, Enclaves minerales en el norte de México: historia social de los mineros de Cananea y Nueva Rosita, 1900-1970 (Mexico City: Casa Chata, 1988), 37, 198-199; Evelyn Hu-DeHart, “Voluntary Associations in a Predominantly Male Immigrant Community: The Chinese on the Mexican Northern Frontier, 1880-1930,” unpublished manuscript, in the authors’ possession. Evelyn Hu-DeHart, “Immigrants to a Developing Society: the Chinese in Northern Mexico, 1875-1932,” Journal of Arizona History 21 (Autumn, 1980): 49-86; Charles C. Cumberland, “The Sonora Chinese and the Mexican Revolution,” The Hispanic American Historical Review 40.2 (May, 1960): 191-211; James W. Russell, Class and Race Formation in North America (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2008), 65. ↩

4 Michael J. Gonzalez, “U.S. Copper Companies, the Mine Workers’ Movement, and the Mexican Revolution, 1910-1920,” The Hispanic American Historical Review 76.3 (August, 1996): 503-534, at 506; Ramón Eduardo Ruiz, The People of Sonora and Yankee Capitalists (Tucson: University of Arizona Press, 1988). ↩

5 Malcolm J. Rohrbough, Days of Gold: the California Gold Rush and the American Nation (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1997); J. Fred Rippy, “The Indians of the Southwest in the Diplomacy of the United States and Mexico, 1848-1853,” The Hispanic American Historical Review 2.3 (1919): 363-396, at 383. For an attack on Chinese “weaknesses” and “lack of morals,” see El Siglo XIX (Mexico City) October 24, 1871, quoted in José Jorge Gómez Izquierdo, El movimiento antichino en México, 1871-1934 (Mexico City: INAH, 1991), 46-47; Kanji Sato, “Formation of La Raza and the Anti-Chinese Movement in Mexico,” Transforming Anthropology 14.2 (2006): 181-186. ↩

6 Shehong Chen, Being Chinese, Becoming Chinese American (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2002), 34-36; Leo M. Dambourges Jacques, “The Chinese Massacre in Torreon (Coahuila) in 1911,” Arizona and the West 16.3 (Autumn, 1974): 233-246 ↩

7 John Harner, “Place Identity and Copper Mining in Sonora, Mexico,” Annals of the Association of American Geographers 91.4 (December, 2001): 660-680, at 660. See also Hu-DeHart, “Indian and Immigrants on a Developing Frontier,” 199. ↩

8 David Eng, Racial Castration: Managing Masculinity in Asian America (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2001). For gender and the colonial tradition of Chinese as servants, see Julia Martínez and Claire Lowrie, “Colonial Constructions of Masculinity: Transforming Aboriginal Australian Men into ‘Houseboys’,” Gender & History 21.2 (August, 2009): 305-323. ↩

9 Gaceta de Cananea (Cananea), September 6, 1908. ↩

10 On categories of race in late 19th and early 20th Centuries, see John Higham, “American Immigration Policy in Historical Perspective,” Law and Contemporary Problems 21.2 (Spring, 1956): 213-235, at 224-226. ↩

11 Gaceta de Cananea, September 13, 1908. ↩

12 Higham, “American Immigration Policy,” 216. On the notion of disgust and hate, see Martha Nussbaum, From Disgust to Humanity: Sexual Orientation and Constitutional Law (New York: Oxford University Press, 2010). ↩

13 Gaceta de Cananea, September 13, 1908. ↩

14 The historical period known as the “Porfiriato” is named after President Porfirio Díaz, who ruled Mexico practically from 1876 to 1910. Raymond B. Craib III, “Chinese Immigrants in Porfirian Mexico: A Preliminary Study of Settlement, Economic Activity and Anti-Chinese Sentiment,” LAII Research Paper Series No. 28 (Albuquerque: Latin American and Iberian Institute, University of New Mexico), May 1996. ↩

15 Gaceta de Cananea, October 4, 1908. ↩

16 Leo Michael Dambourges Jacques, “The Anti-Chinese Campaigns in Sonora, Mexico, 1900-1931” (Ph.D. dissertation, The University of Arizona, 1974), 88; Leo M. Jacques, “Have a Quick More Money Than Mandarins: The Chinese in Sonora,” Journal of Arizona History 17.2 (Summer, 1976): 201-218. ↩

17 For Arana’s biography, see http://content.library.arizona.edu/collections/asdo ↩

18 Jacques, “The Anti-Chinese Campaigns in Sonora,” 110. ↩

19 José Ángel Espinoza, El ejemplo de Sonora (Mexico City: n.e., 1932), 32; Jacques, “The Anti-Chinese Campaigns in Sonora,” 114. ↩

20 Gerardo Réñique, “Región, raza y nación en el antichinismo sonorense: cultura regional y mestizaje en el México posrevolucionario,” in Seis expulsiones y un adiós. Despojos y exclusiones en Sonora, edited by Aarón Grageda Bustamante, 231-289 (Mexico City: Universidad de Sonora/Plaza y Valdés, 2003), 254. ↩

21 Hermosillo, Sonora. Casa de la Cultura Jurídica (henceforward CCJ). “Ley del Trabajo y de la Previsión Social.” Salón de Sesiones del H. Congreso del Estado. Hermosillo, March 31, 1919. ↩

22 http://content.library.arizona.edu/collections/asdo Papers of José María Arana. Box 1, folder 4: 1919. R. R. González to José María Arana. Cananea, August 4, 1919. It was illegal for the mayor to force an inmate to clean up the prison. ↩

23 Gaceta de Cananea, September 13, 1908. ↩

24 College Park, Maryland. National Archives (NA). Record Group (RG) 59. State Department Records (SDR) 812.5593/23. Francis J. Dyer to Secretary of State. Nogales, Sonora, January 29, 1920. ↩

25 James R. Curtis, “Mexicali’s Chinatown,” Geographical Review 85.3 (July, 1995): 335-348; Kay J. Anderson, “The Idea of Chinatown: The Power and Place and Institutional Practice in the Making of a Racial Category,” Annals of the Association of American Geographers 77.4 (December, 1987): 580-598; Rose Hum Lee, “Social Institutions of a Rocky Mountain Chinatown,” Social Forces 27.1 (October, 1948-May, 1949): 1-11. ↩

26 Jacques, “The Anti-Chinese Campaigns in Sonora,” 136. For the law that created Chinese barrios in Sonora during the early 1920s, see CCJ # 330-A/924. “Ley que crea los barrios chinos en el Estado,” December 8, 1923, 6f. ↩

27 NA RG 59. SDR 5593/17. Letter from Gibbs to Dyer quoted in letter from Francis J. Dyer to Secretary of State. Nogales, Sonora, December 28, 1919. ↩

28 NA RG 59. SDR 812.5593/12. Francis J. Dyer to Secretary of State. Nogales, Sonora, December 10, 1919. ↩

29 NA RG 59. SDR 812.5593/13. Telegram from Francis J. Dyer to Secretary of State. Nogales, Sonora, December 27, 1919. ↩

30 NA RG 59. SDR 5593/17. Letter from Gibbs to Dyer quoted in letter from Francis J. Dyer to Secretary of State. Nogales, Sonora, December 28, 1919. ↩

31 NA RG 59 SDR 812.5583/20. Telegram from Dyer to Secretary of State. Nogales, Sonora, January 7, 1920. ↩

32 NA RG 59 SDR 5593/23. Letter from Gibbs to Dyer quoted in letter from Dyer to Secretary of State. Nogales, Sonora, January 29, 1920. The words in italics were underlined by hand. ↩

33 Hu-DeHart, “Immigrants to a Developing Society”; Sato, “Formation of La Raza,” 182; Gary D. Livingstone, “Racism and the Passage of Immigration Act of 1924: The Beginning of the Quota System,” Journal of Borderland Studies 8.2 (Fall, 1993): 73-90. ↩

34 Geraldo Renique, “Race, Region, and Nation: Sonora’s Anti-Chinese and Mexico’s Postrevolutionary Nationalism, 1920s-1930s,” in Race and Nationalism in Modern Latin America, edited by Nancy P. Applebaum, Anne S. Macpherson, and Karin Alejandra Rosemblat, 211-236 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2003), 228. ↩

35 Sato, “Formation of La Raza,” 182. ↩

36 Mercedes Carreras de Velasco, Los mexicanos que devolvió la crisis, 1929-1932 (Mexico City: Secretaría de Relaciones Exteriores, 1974). ↩

37 Sato, “Formation of La Raza,” 182. Defined as illegal immigrants, the Chinese were later deported by the United States government from San Francisco back to China. ↩

38 College Park, Maryland. National Archives (NA). Military Intelligence Division (MID). 2657-657/76. Confidential letter from Robert S. Know to the Assistant of the Chief of Personnel, G-2, 8th Corps Area, Fort Sam Houston, Texas. Nogales, Arizona, February 26, 1932. ↩

39 NA MID 2657-657/76. Know to the Assistant of the Chief of Personnel. February 26, 1932. ↩

40 In the United States, see Roger D. Hardaway, “Unlawful Love: A History of Arizona’s Miscegenation Law,” Journal of Arizona History 27.4 (Winter, 1985): 327-262. ↩

41 Hu-DeHart, “Immigrants to a Developing Society”; May Q. Wong, “The Chinese Community in Mazatlan: A Journey from Past to Present, Part I,” Mazatlan Pacific Pearl’s Online http://www.pacificpearl.com/archive/2006/May/feature1.htm Joe Cummings, “Sweet And Sour Times On The Border,” Mexconnect http://www.mexconnect.com/articles/1310-sweet-and-sour-times-on-the-border Curtis, “Mexicali’s Chinatown.” ↩

42 Espinoza, El ejemplo de Sonora. Espinoza was one of the most outspoken activists of the anti-Chinese movement. He drafted the constitution of the Federal District Pro-Raza Committee. ↩

43 Roger Daniels, The Politics of Prejudice: The Anti-Japanese Movement in California and the Struggle for Japanese Exclusion (Gloucester, Mass.: Peter Smith, 1966). ↩

44 Raymond Leslie Buell, “The Development of the Anti-Japanese Agitation in the United States,” Political Science Quarterly 37.4 (December, 1922): 605-638, at 613; Eldon R. Penrose, California Nativism: Organized Opposition to the Japanese, 1890–1913 (San Francisco: R and E Research Associates, 1973). ↩

45 Raymond Leslie Buell, “The Development of Anti-Japanese Agitation in the United States II,” Political Science Quarterly 38.1 (March, 1923): 57-81, at 57; David J. Hellwig, “Afro-American Reactions to the Japanese and the Anti-Japanese Movement, 1906-1924,” Phylon 38.1 (1st Quarter, 1977): 93-104, at 93. ↩

46 Daniel Masterson, The Japanese in Latin America (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2004); Toake Endoh, Exporting Japan (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2004); Inés Sanmiguel, “Japoneses en Colombia. Historia de inmigración, y sus descendientes en Japón”, Revista de Estudios Sociales 23 (April, 2006): 81-96. ↩

47 Eric Waltz, “From Kumamoto to Idaho: The Influence of Japanese Immigrants on the Agricultural Development of the Interior West,” Agricultural History 74.2 (Spring, 2000), 404-418. ↩

48 Eric Walz, “The Issei Community in Maricopa County: Development and Persistence in the Valley of the Sun, 1900-1940,” The Journal of Arizona History 38 (Spring, 1997): 1-22. ↩

49 John Higham, “American Immigration Policy in Historical Perspective,” Law and Contemporary Problems 21.2 (Spring, 1956): 225-230; Donald Teruo Hata, “Undesirables”: Early Immigrants and the Anti-Japanese Movement in San Francisco, 1882-1893. Prelude to Exclusion (New York: Arno Press, 1978). ↩

50 Karen J. Leong and Dan Killoren, “Enduring Communities: Japanese Americans in Arizona,” Discover Nikkei, May 30, 2008. http://www.discovernikkei.org/en/journal/2008/5/30/enduring-communities Gary P. Tipton, “Men Out of China: Origins of the Chinese Colony in Phoenix,” Journal of Arizona History 18.3 (Autumn, 1977): 345-356. ↩

51 Jack August, “The Anti-Japanese Crusade in Arizona’s Salt River Valley: 1934-35,” Arizona and the West 21.2 (Summer, 1979), 114-115; Susie Sato, “Before Pearl Harbor: Early Japanese Settlers in Arizona,” Journal of Arizona History 14 (Winter, 1973): 317-334. ↩

52 Walz, “The Issei Community”; Leong and Killoren, “Enduring Communities.” ↩

53 Walz, “The Issei Community”; Stanford M. Lyman, “Contrasts in the Community Organization of Chinese and Japanese in North America,” in The Asian in North America, edited by Stanford M. Lyman, 119-130 (Santa Barbara, California: ABC-Clio, 1977), 125. ↩

54 NA RG 59. SDR 811.5294/510 and NA RG 59. SDR 811.5294/511. “Anti-Oriental Activities Among Farmer Population in the Neighborhood of Phoenix, Arizona,” August 22, 1934. Jack August, “The Anti-Japanese Crusade,” 115-116. ↩

55 NA RG 59. SDR 811.5294/501. “No Violence Promised in Jap Trouble,” excerpt from the Douglas Daily Dispatch, August 23, 1934. Enclosure with Letter from Lewis V. Boyle, US Consul, to the Secretary of State. Agua Prieta, Sonora, August 23, 1934. ↩

56 August, “The Anti-Japanese Crusade,” 117-118. ↩

57 NA RG 59. SDR 811.5294/509. William Phillips, “Memorandum of conversation with the Japanese Chargé d’Affaires.” Washington, D.C., August 20, 1934. ↩

58 NA RG 59. SDR 811.5294/501. “Japan U.S. Relations Protected,” excerpt from the Douglas Daily Dispatch, August 22, 1934. Enclosure with letter from Lewis V. Boyle to Secretary of State. Agua Prieta, Sonora, August 23, 1934. ↩

59 NA RG 59. SDR 811.5294/496A. Telegram from William Phillips to Governor of Arizona. Washington, D.C., August 21, 1934. ↩

60 NA RG 59. SDR 811.5294/497. Telegram from Arthur T. Laprade to William Phillips. August 21, 1934; NA. RG 59. SDR 811.5294/498. Telegram from B.B. Moeur to William Phillips, August 22, 1934. ↩

61 NA RG 59. SDR 811.5294/499. Telegram from B.C. Kent, Secretary, Anti-Alien Association Committee to acting Secretary of State William Phillips. Phoenix, Arizona, August 22, 1934. ↩

62 NA RG 59. SDR 811.5294/499. Kent to Phillips. August 22, 1934. ↩

63 NA RG 59. SDR 811.5294/499. Kent to Phillips. August 22, 1934. ↩

64 NA RG 59. SDR 811.5294/499. Kent to Phillips. August 22, 1934. ↩

65 NA RG 59. SDR 811.5294/505. “White Farmers Appear to Win Against Aliens,” excerpt from the Douglas Daily Dispatch, August 29, 1934. Enclosure with Lewis W. Boyle to Secretary of State. Agua Prieta, Sonora, August 29, 1934. ↩

66 NA RG 59. SDR 811.5294/506. “Moeur is Told White Farmers Dissatisfied,” excerpt from the Douglas Daily Dispatch, August 30, 1934. Enclosure with Lewis W. Boyle to Secretary of State. Agua Prieta, Sonora, August 30, 1934. ↩

67 Walz, “The Issei Community.” ↩

68 Brian Niiya, Japanese American History: An A-to-Z Reference from 1868 to the Present (New York: Facts-on-File, 1993), 302. ↩

69 “Four Face Charges in Alien Case,” Los Angeles Times (Los Angeles), September 5, 1934. NA RG 59. SDR 811.5294/515. Memorandum of conversation between Mr. Hornbeck, of the Department of State, and Arthur LaPrade, attorney general of the State of Arizona. August 21, 1934. ↩

70 NA RG 59 SDR 511.5294/517. “Night Riders Reported Active in Valley of Salt,” excerpt from the Douglas Daily Dispatch, September 14, 1934. Enclosure with Lewis V. Boyle to Secretary of State. Agua Prieta, Sonora, September 14 1934; “Night Riders Use Bombs Against Arizona Aliens,” Los Angeles Times, September 20, 1934. ↩

71 NA RG 59. SDR 811.5294/519. “Jap Charges Bombs Used on Ditches,” excerpt from the Douglas Daily Dispatch, September 20, 1934. Enclosure with Lewis V. Boyle to the Secretary of State. Agua Prieta, Sonora, September 20, 1934. ↩

72 “The Arizona Bombings,” Los Angeles Times, September 21, 1934. ↩

73 “Arizona News,” September 3, 1934. Arizona Trails History Group. http://genealogytrails.com/ariz/news.html ↩

74 NA RG 59. SDR 811.5294/527. B.B. Moeur to Cordell Hull. Phoenix, October 4, 1934. ↩

75 NA RG 59. SDR 811.5294/546. “Protest Against Alien Land Law Violence Issued,” excerpt from the Douglas Daily Dispatch, November 1, 1934. Enclosure with Lewis V. Boyle to the Secretary of State. Agua Prieta, Sonora, November 1, 1934. ↩

76 NA RG 59 SDR 811.5294/551. Frank H. Smith to the Honorable F.D. Roosevelt. Berkeley, California, October 31, 1934. ↩

77 “Answer to Japanese Dodger. Peace, peace, peace!,” newspaper clipping, October 31, 1934. Enclosure with letter from Frank H. Smith, superintendent of The First Methodist Episcopal Church, to the Honorable F. D. Roosevelt. Phoenix, October 31, 1934. ↩

78 “Answer to Japanese Dodger. Peace, peace, peace!,” Douglas Daily Dispatch, October 31, 1934. ↩

79 August, “The Anti-Japanese Crusade,” 136. ↩

80 NA RG 59. SDR 811.5294/562. Telegram of William Phillips to the American embassy in Tokyo. Washington, D.C., December 11, 1934. ↩

81 E. J. Webster, “Stiff anti-Japanese Bill Creates Stir in Arizona,” New York Times (New York), February 17, 1935. ↩

82 Webster, “Stiff anti-Japanese Bill,” New York Times, February 17, 1935. ↩

83 NA RG 59. SDR 811.5294/571. Strictly confidential telegram from William Phillips to the US embassy in Tokyo. Washington, D.C., February 23, 1935. NA RG 59. SDR 811.5294/576. “Drastic Measures to Stop Aliens in the Legislature,” excerpt from the Douglas Daily Dispatch, February 19, 1935. Enclosure with Lewis V. Boyle to Secretary of State. Agua Prieta, Sonora, February 19, 1935. ↩

84 NA RG 59. SDR 811.5294/583. “Legislature is Petitioned About Alien Land Bill,” excerpt from the Douglas Daily Dispatch, March 12, 1935. Enclosure with letter from Lewis V. Boyle to the Secretary of State. Agua Prieta, Sonora, March 12, 1935. ↩

85 NA RG 59. SDR 811.5294/581. Clifton Mathews, United States Attorney, to William Stanley, Assistant to the Attorney General, Department of Justice. Phoenix, Arizona, February 27, 1935. Enclosure with letter from William Stanley to the Secretary of State. Washington, D.C., March 7, 1935. ↩

86 “Legislature is Petitioned About Alien Land Bill,” Douglas Daily Dispath, March 12, 1935. ↩

87 NA RG 59. SDR 811.5294/585. “Alien Land Bill May Pass Legislature as Last Item,” excerpt from the Douglas Daily Dispatch, March 16, 1935. Enclosure with letter from Lewis V. Boyle to the Secretary of State. Agua Prieta, Sonora, March 16, 1935. ↩

88 August, “The Anti-Japanese Crusade,” 113-136. ↩

89 See Jean Meyer, “Yo, el otro,” in Seis expulsiones y un adiós. Despojos y exclusiones en Sonora, edited by Aarón Grageda Bustamante, 291-301 (Mexico City: Universidad de Sonora/Plaza y Valdés, 2003), 298. ↩

90 On the idea of home, place, and geography, see Alison Blunt and Robyn Dowling, Home (London: Routledge, 2006). ↩

91 John Fitzgerald, Big White Lie: Chinese Australians in White Australia (Sydney: UNSW Press, 2007); Andrew Markus, Fear and Hatred: Purifying Australia and California, 1850–1901 (Sydney: Allen & Unwin, 1979), and Julia Martínez and Claire Lowrie, “Colonial Constructions of Masculinity,” 308-311. On anti-Asian attitudes and restrictions in the British dominions see Kornel Chang, “Circulating Race and Empire: Transnational Labor Activism and the Politics of Anti-Asian Agitation in the Anglo-American Pacific World, 1880–1910,” Journal of American History 96.3 (December, 2009): 678-701; Erika Lee, “The ‘Yellow Peril’ and Asian Exclusion in the Americas,” Pacific Historical Review 76 (November, 2007), 537–562. ↩

92 Bradford Luckingham, Minorities in Phoenix: A Profile of Mexican Americans, Chinese Americans, and African American Communities, 1860-1992 (Tucson: University of Arizona Press, 1994). ↩