The screening of Alice’s adventures in Wonderland has always constituted a veritable challenge to film-makers because the literary stature earned by the dream-like narrative structure, nonsensical wordplay and ambiguous meanings of Lewis Carroll’s Victorian fantasy classics proved ever so difficult to translate into the cinematic medium. Nevertheless, since the first filmic revision of the novel in 1903 (in Hepworth and Stow’s ten-minutes-long silent movie, only five years after Carroll’s death), the numerous moving image adaptations have pervaded cultural imagination to such an extent that Alice ceases to be simply read as a heroine of children’s literature. Her enigmatic charm prevails, but she is no longer inseparable from Lewis Carroll’s bizarre literary bricolage of fairy tale, nonsense fantasy, and gothic horror, “a combination of text and image, of fantasy and reality, of the abstract and the concrete” that so perplexingly fused social-critical allegory, political satire, literary parody, philosophical language-games, playfully thought-provoking paradox and infantile gibberish to provide “meaning and enjoyment” (Ennis in Zipes 2000, 12) to child and adult readers alike. Today, Alice is rather regarded as a visual product sprung from the “magical world” of Walt Disney, American McGee, Hello Kitty, or Tim Burton and associated with the animation, the 3D CGI family movie, the computer game, the girly gadgets, or the theme park entertainment, respectively – and an increasing spectacularization, unanimously.

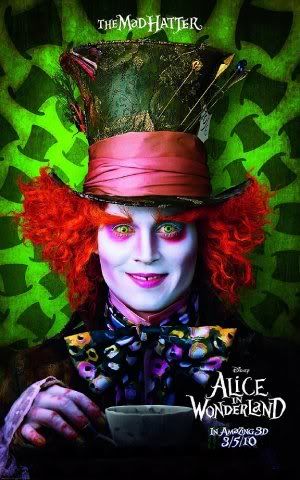

Figures 1, 2, 3, and 4.

As Stephens and McCallum recently argued, the reception of fairy tale fantasies have been heavily influenced by the proliferation of filmic adaptations. Children nowadays are likely to first encounter literary classics mediated by the film industry. The resulting deformation, commercialization, and consumerization of ‘classics’ – mostly by Disney’s patriarchal, capitalistic formula – are among the major concerns of cultural critics. Many believe that the universal human values embedded in the story’s archetypal structure and characterization are inevitably distorted by the specific socio-historical conditions and ideological interests propagated by the cultural industry of the production’s own era (Stephens and McCallum in Zipes 2000, 160; also see Pilinovsky in Kérchy 2011, 17-33), while imagination (in particular female imagination) is encouraged only to be punished, to reward a return to realism (and the prevailing hegemonic power structures) (Ross in Cartmell 210).

However, here, instead of problematizing the ‘original’s’ ‘deformation’ by the adaptation, I wish to study the status of the fairy tale fantasy film after Mitchell’s pictorial turn, a late 20th century paradigm shift (and the problem of the 21st century) marked by an extension and diversification of visual culture, and a massive preoccupation with pictures and images as primary means of communication, information, control, and ‘fantastification’ in a society of spectacle and an era of simulation. My aim is to analyse the dynamic interaction between textual and pictorial representation, while combining methodologies of reading filmic image as text (e.g.: adapting narratological considerations to cinema) and exploring the visual dis/contents of textuality (e.g.: the inherent figurativity and metaphoricity of language, the significance of illustrations). I intend to examine how/whether the intermedial shifts accompanying the transmission of a literary text to a visual medium, – and (progressing from image to moving image to 3D CGI live-action animation) to a predictably unreliable computerized/digitalized visual medium that depicts mimetically ‘what has never been’ – bring about changes in our predominant modalities of experience that affect our perception of reality, as well as our strategies of make-believing, the dynamic interaction of our imaginative willingness and reluctance, and our interactive ways of making sense, and making up nonsense.

I shall focus on Tim Burton’s 2010 cinematic adaptation of Lewis Carroll’s Alice-tales with the aim to explore the different modes of dis/enchantment that media change – the adaptation’s transition from verbal to visual (means of effecting) nonsense – effectuate.1 With a Carroll-Burton interface, I intend to prove that the change in media is never absolute or exclusionary, for both the Victorian and postmodern eras are characterised by an inter/multi-medial con/fusion, where different media – as diverse means of representation – complement instead of substituting one another. Even if Burton’s computer animated live-action fantasy adventure movie stages a superbly spectacularized Alice with an emphasis on dazzling visual effects, easy entertainment, and ‘hard’ technology instead of a wildly imaginative, wittily crafted, thought-provoking storyline and sophisticated wordplay, it also revives an original value of the Carrollian literary masterpiece, namely its image-text quality. Thus, it provides a perfect illustration to Henry Jenkins’ and David Thornburn’s argument in so far as it reveals that “media transition is always a mix of tradition and innovation, an accretive process in which emerging and established [visual/verbal] systems interact, shift, and collude with one another” (x).

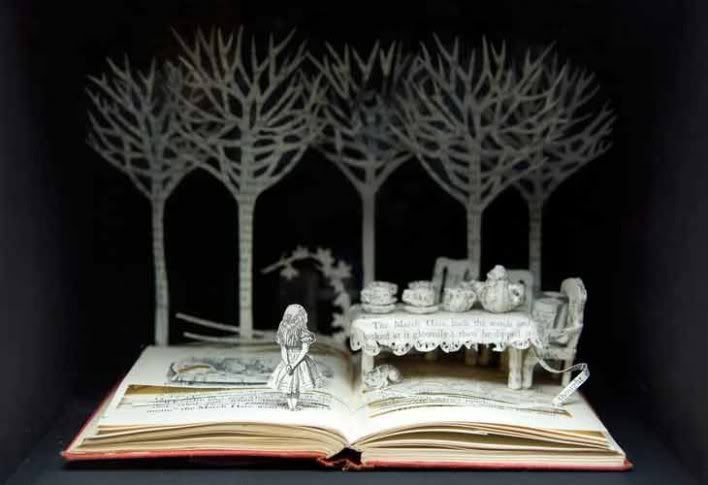

Figure 5.

Moving-image adaptations of Alice, like all works classified as children’s films, have been frequently and simplistically evaluated along the lines of fidelity to the literary source-text. (see Street, Wojcik-Andrews cited in Szabó 12, Brooker 200) The mythic primacy of words as origins of images prevails despite the fact that the number of “duplications” which simply perpetuate the original’s canonical form, plot or moral is indubitably surpassed by the “critical revisions” which subvert the story by incorporating new values, perspectives, aesthetics or politics to it (Zipes 1994, 8-9), or “creative revisions” which “rather gain inspiration from the original, to reimagine the same fantasy patterns with a different manifest dream content” (Kérchy in McAra-Calvin 67). (Alice Redux edited by Richard Peabody (2005) and Carolyn Sigler’s collection, Alternative Alices (1997) gather dozens of these creative revisions from the field of literature.) When Tim Burton calls his recent film adaptation of Alice neither a sequel, nor a reimagining, but an “extension” (Ryder 2009), he seems to highlight the challenge imposed by those complex multi-volume tales – such as Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland (1865) followed by Through the Looking Glass And What Alice Found There (1871) – which already constitute a dialogic unit of Genettian hypotext, and thus almost necessarily elicit further polylogical variants, con/fusing episodes, characters and puns of the two books within the single new retelling – mostly under the simplified title Alice in Wonderland. Interestingly, this post/modernist tendency of the cinematic adaptation’s relying on a multitude of preceding hypotexts, paratexts, and adoptions across different media instead of one single particular source-text also signifies a return to the very archaic origins of the fairy tale genre distinguished by a proliferation of anonymous, orally transmitted versions, “a myriad of indeterminate intervening retellings” (Stephens and McCallum in Zipes 2000, 161).

Moreover, the contemporary difficulty in defining the generic category of children’s film (alternatively regarded as designed for/about/by children, or from a children’s literary classic) and its gradual blurring with the category of family movie point towards another fundamental feature of fairy tales: the traditional collective intent to please and instruct mixed-aged audiences. (Of course, the addressing of a dual reader/spectatorship is even more legitimate when it comes to screening Carroll’s bizarre literary bricolage.) After all, Burton’s very twenty-first century, postmodernist adaptation featured on the International Movie Data Base, instead of a children’s film, as a “live-action family adventure film” rated PG (Parental Guidance advised) by the Motion Picture Association of America “for fantasy action/violence involving scary images and situations, and for a smoking caterpillar” may not be so far from the fairy tale – and Carrollian classics – full of explicit violence, social critical commentary and sexual innuendo – as one would presume at first sight.

Interestingly, even the most postmodernist feature of contemporary children’s film, metafictionality, can be traced back to a subversive strand of the fairy-tale tradition. The late 17th century French aristocratic literary salons’ women-writer-conteuses used an elaborate Chinese box- or Russian doll-like narrative structure to tell a story within a story about storytelling (see Wanning Harries 107), and thus lurk as literary foremothers behind films that employ a visual narrative mise-en-abyme to reflect on their fictional universe’s own constructedness, and consequently, its (fantasy) reality’s relativity and potential unreliability. Metatexts are also inherently intertextual, and make self-reflexive, self-referential commentaries on other texts besides themselves, so that they equally blur the dividing lines between fantasy worlds, and (original literary) textual and (filmic adaptation’s) visual regimes, as well as between fictional and real world, character and reader, imaginative willingness and reluctance, alike.

By way of a popular manifestation of this metatextuality, a recurring initial scene of numerous children’s movies – including Disney’s Winnie the Pooh, Beauty and the Beast, Sleeping Beauty or Dreamworks’ Shrek – feature in the film’s first shots the opening up of a book as an authentic portal that can guarantee the entry into the fictional realm through invoking the archaic act of storytelling whereby the tale is going to be read just as much as shown to the audience. This scene does not only illustrate the indebtedness of the visual to the textual, but also stages an exciting image-text interaction complemented by the auditory component of the voice (and the commemoration of the oral origins of fairy tales) as the story’s atemporal, eternal charm is guaranteed by its ‘retellability,’ the fact that it can be retold over and over again to a changing audience of eager listeners.

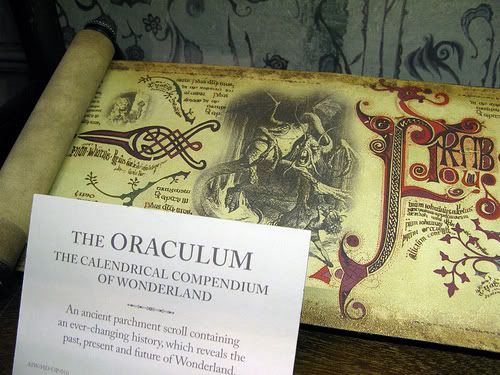

Another typical metafictional image-text interaction surfaces on occasions when the primordial subtext lurking beneath the visual adaptation is materialized in the form of a book or a scripture the alternate cinematic reality’s characters (usually including the Alice-alterego figure) are reading or enacting. This might be a book literally entitled Alice in Wonderland (as in the postmodern revisions, Terry Gilliam’s Tideland (Fig.6) or Guillermo del Toro’s Pan’s Labyrinth) or a manuscript like Burton’s Wonderland scrolls, an oraculum-compendium-calendar that featured the novel’s original, most famous illustration of the monstrous Jabberwock by Victorian artist John Tenniel. Burton’s recycling of Tenniel’s addendum to Carroll, on the one hand, accelerates the metafictional image-text dynamics by embedding a major paratext, an image (complementing a novelistic text) into/within cinematic moving image medium, and on the other, significantly calls attention to the extremely visual nature of the Carrollian text, and of the inherent textuality of the filmic image.

Figure 6.

As for the visuality of the text, the Alice tales have been conceived from the very beginning as picture books. The title-character’s initial, rhetorical question at the beginning, in the very first sentence of the book: “And what is the use of a book, without pictures or conversation?” (Caroll 11) metatextually locates the image-text within the dolce et utile tradition, as spectacularly joy- and use-ful read – in fact the only read that is worth reading. The 1951 Disney classic takes on this metanarrative celebration of visuality (and visual adaptations) when Alice, an animated picture herself, fantasizes about making a “‘world of my own’ in which every book would be nothing but pictures” (Ross in Cartmell 218).

Alice’s original maker was indeed a highly visual storyteller, too: Carroll was used to illustrating the tales he was telling to his childfriends “by pencil or ink drawings as he went along” (Green in Phillips 14), and he carefully designed and decorated the hundreds of rebus-letters he sent them (– that led some critics to argue that his novel on Alice “is nothing more than an elaborately illustrated letter” (Susina 15)). Small wonder that when he penned down the tale he improvised on that famous boating trip for Alice Liddell and her sisters, he decorated the manuscript with his own 37 sketches in a carefully hand-printed gift-copy he offered to his child-muse in 1863.2

Figure 7.

When this preliminary short version initially entitled Alice’s Adventures under Ground was later rewritten and extended into the publicly available form we are familiar with today as Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, Carroll invited the chief cartoonist for Punch, Sir John Tenniel to provide a more refined pictorial form to his fantasies. The artist’s 42 wood-engraved drawings (Fig. 8) were prepared under the personal supervision, and in line with the meticulous instructions of the author who bombarded his illustrator with suggestions and criticism throughout their prickly but fruitful collaborative partnership. The importance attributed to the illustrations is shown by the fact that the first print run of 2000 copies in 1865 was destroyed at the perfectionist creators’ request because they were dissatisfied with the images’ “disgraceful printing” (Ray 116), and the book was reprinted in 1866.

Figure 8.

As Janis Lull notes, “in both the Alice books, the Tenniel illustrations are so important that one would expect to find each detail reinforcing the design of the book as a whole” (91). Sometimes the images are presumed to be even more telling than any verbal descriptions could be: in the Mock Turtle chapter Carroll invites readers to “look at the picture” “if you don’t know what a gryphon is” (98), as if half-mocking the failure of language upon affronting such unspeakably fantastic phenomenon. (Funnily enough the reverse case of images failing words emerged too when Carroll had to omit his episode on the wasp in a wig because Tenniel, as he claimed in his letters, “[couldn’t] find [his] way to a picture,” and judged this part of the narrative to be pictorially unrepresentable, un-imaginable, “altogether beyond the appliances of [visual] art.” (Collingwood 131, Cohen-Wakeling 15)) On other occasions, the illustrations instead of facilitating the understanding of neologisms’ referentless signifiers like the Jabberwock or the “slighty toves” described as “something like badgers,” “something like lizards,” and “something like corkscrews” (Carroll 226) increase the nonsensical effect by depicting impossible, mutant, proto-surrealistic fantasy-creatures.

The pictures constitute such an integral part of the text that we tend to associate the Alice-novels with immense visual powers, despite the fact that, as Richard Kelly remarks, Carroll practically hardly gives any precise physical description of his characters; e.g.: the only details we learn about the title character’s appearance are that “she had long, straight hair, shiny shoes, a skirt, small hands, and bright eyes” (Kelly 55). The nearly consensual association of Wonderland with the mental image of a blonde little girl in a blue pinafore is based on Tenniel’s colour illustrations to the Nursery Alice, “inextricably wedded to the total performance of the work.” (Kelly 52 in Guiliano)

Nevertheless, in Carroll’s textual narrative about Alice – who is unable, like her readers, to make sense in a world, where logic and language turn topsy-turvy – it is linguistic representation that gains a pictorial quality. The disorientation by picturesque language is foregrounded verbally by literalised metaphors and idiomatic expressions (“mad (as a) hatter,” “grin like a Cheshire cat”), mirrored verses (Alice first sees the Jabberwocky poem in the reverse), typographical play and picture poems or figured verse, the “visual analogue of poetic onomatopoeia,” and “artistic chirography,” (see Gardner’s note in Carroll 35) (when a tale may take the form of the mouse’s tail it describes). Moreover, Carroll’s picturesque, figurative language often gains literalized image-form by virtue of their graphic translations into visual puns on Tenniel’s drawings of mad hatters, grinning cats and foot notes.

The all-pervasive influence of the Tenniel-illustrations is highlighted in Staples’ entry on Alice in Wonderland in Film in Jack Zipes’ companion to fairy tales that mostly consists of an enumeration of filmic attempts to recreate the woodcut drawings’ wondrous atmosphere by odd means, such as Tenniel-style masks hiding the face of stars like Gary Cooper (White Knight) or Cary Grant (the Mock Turtle) in the 1933 adaptation, or more than a hundred Tenniel-based, stop motion-animated, grotesque puppets in the 1949 version (Staples in Zipes 12-13), and a truly authentic but somewhat goofy 3D reconstruction of Tenniel’s original Jabberwock with bulging eyes, protruding teeth, and a scaly waistcoat in SyFy channel’s recent 2009 filmic reimagining.

Figure 9.

Curiously, one of the most well-known Tenniel drawings remains one of a kind: it is the only, and thus still, the defining depiction we have of the enigmatic monster, Jabberwock, who is introduced as a prominent part of Wonderland’s mythology in a nonsense poetic tale embedded within Alice’s adventure story.

Figure 10.

The Jabberwock/y3 earns the status of metafictional image-text both extra- and intratextually. Readers’ imagination is perplexed by the literary nonsensical ambiguity of this “whiffling,” “burbling” creature with “jaws that bite” and “claws that clash,” and ends up being guided by the Tenniel-illustration that grants a possible visual form to what has emerged in the poetic text as “a name without a thing,” a referentless signifier, an undefinable, faceless, formless enemy. Nevertheless, Tenniel stays true to Carroll’s poetic ambiguity – and may even grant a visual form to the literary text’s potential inspirations of legendary, mythological, and scientific origins – on creating a grotesque hybrid, a monstrously degenerate mutant by fusing features of dragons, griffins, dinosaurs, beetles, and the legendary Lambton Worm. Within the fictional universe, Carroll’s Alice never meets the Jabberwock itself, but encounters the poetic text about him in the inverted world behind the Looking Glass, in a mirror-writing she first decodes as a strange language she cannot read, since the words turned topsy-turvy, from right to left/wrong are first perceived by her more as non-figurative images than linguistic signs. For Alice the Jabberwock remains a textual product (initially reminiscent of an image) that never takes a visible physical form – what fascinates and frustrates Alice is not so much the vincibility of the mythical creature but the in/comprehensibility of the discourse about him. “‘It seems very pretty,’ she [says…] ‘but it’s rather hard to understand!’ […] ‘Somehow it seems to fill my head with ideas – only I don’t exactly know what they are! However, somebody killed something: that’s clear, at any rate.’” (Carroll 156) What is at stake here is the manageability and enjoyability of the textual monstrosity of nonsensical representation.

Along these lines, in the following, I wish to focus on the Jabberwock’s verbal and visual manifestations and their interpretive experience by real and implied readers to explore how Carroll’s original literary language-games are complemented and complicated with pictorial illustrations to reach discursive nonsensification, and how in Burton’s cinematic extension verbal and vocal means of creating nonsense serve to enhance overall visual effects. I wish to prove that from the beginnings, the Jabberwock can be regarded as an iconic figure of nonsense nested at the peak of incomprehensibility and improbability, of unspeakability and unimaginability, amidst utter image-textual confusion, while playing on the dynamic interaction of enchantment and disenchantment, imaginative willingness and reluctance.

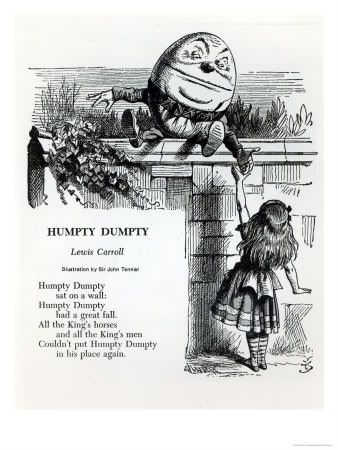

Tenniel’s drawing of the Jabberwock was initially planned as a frontispiece to Through the Looking Glass, but became relegated to the middle of chapter one to calm the mothers of prospective readers who feared that this “too terrible monster” likely would “alarm nervous and imaginative children[‘s]” fantasies (note in Carroll 163), as the embodiment of the Unimaginable itself. However, as Michael Hancher highlights, the frail childlike knight ready to slay the monster with the vorpal sword closely resembles another Tenniel illustration that portrays Alice in a similar posture: from the back, with her long hair hanging down, and slightly leaning back to look upon another nonsensical Wonderland-figure, Humpty Dumpty. The egg-man takes the Jabberwock’s place in the image-composition while he explains word-by-word the mirror-poem about the monster to Alice, and takes the maximal interpretive liberty, defines meanings arbitrarily at whim, and “makes words mean” “just what [he] choose[s] them to mean – neither more, nor less” (Carroll 224).

Figure 11.

Thus, in my view, Humpty Dumpty simultaneously tames monstrosity by framing it (monstrous meaninglessness) into meaning, but he also becomes monstrous himself by tyrannically usurping himself the right to make sense, to make words mean whatever he wants them to mean. While Hancher claims that this scene is “an androgynous projection of Alice’s fears” (1985, 75) I would go further along these lines and stress, yet again, the image-textual significance of Carroll’s text, arguing that the exchangeability of the monstrous illustration of the Jabberwock – too terrible to imagine and terribly unimaginable – and of his mis/interpreter Humpty Dumpty – whose absurd explanation’s vain verbalization assumes to transform via a medial shift unimaginability into speakability, but eventually cannot produce but an incomprehensible, unmasterable, unspeakable code (of communication) – further increases meaninglessness instead of resolving it. Accordingly, the fundamental fears of the Unimaginable and the Unspeakable, of visual and verbal representational dead-ends/thresholds of sense, like anxieties concerning the tyrannical control over meaning and the anarchic proliferation of meaninglessness, go hand in hand, and constitute the kernel trauma of the implied reader/spectator Alice. This can only be eased by consolatory nonsense equally functioning on verbal and visual planes, resisting the solidification of signification.

Scriptwriter Linda Woolverton’s memory-morsel concerning her cooperation with director Tim Burton on their latest 2010 filmic adaptation of Alice is clearly suggestive of the difficulty of the clear-cut distinction between verbal and visual creativity: “[Burton, a notoriously visual storyteller] didn’t talk about images. He really sat down and talked to me like a writer. We looked at the words on the paper. He didn’t draw anything in my presence, although I did draw for him, which is crazy.” (Callaghan 2011)

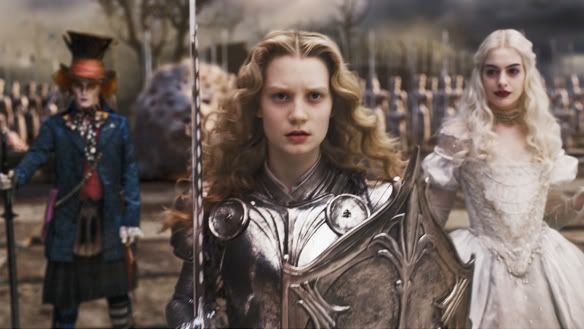

Although Burton’s Alice-movie does not make much use of Carrollian language games, the Jabberwocky nonsense poem plays a prominent role in organising the filmic structure. It provides the basis for a quest- and rite of passage- story in which Alice must find the Vorpal sword and her ‘true’ heroic self to defeat the evil and tyrannic Red Queen by slaying her monstrous pet-dragon, the Jabberwock. Moreover, in Burton – like in the many metafictionally playful children’s films mentioned above – the original image-text (Carroll’s poem and (especially) the accompanying Tenniel-illustration) appear embedded within the cinematic adaptation as decisive readings or prophetic visions apt to change the protagonist’s fate and choices by initiating an exciting play of belief and disbelief, in fantasy and reality.

Accordingly, in the first part of Burton’s film Alice refutes Wonderland as a phantasmagoriac make-believe devalued as Underland, a nightmare she would rather wake up from. As the strange inhabitants say, she has lost her “muchness,” her ability to believe in the authenticity of their fictional realm, and her belonging with them. However, by virtue of an implied readerly identification, she finally accepts the heroic place assigned to her, on witnessing the famed Underland scrolls with the picture of a dragon-slaying knight slightly reminiscent of and clearly identified with her by locals.

Figure 12.

She willingly enters a deeper layer of fiction-within-fiction, as the protagonist of an embedded nonsense anti-tale(within-tale) in Wonderland’s fictional realm’s mythology about the beamish Childe fighting the monstrous Jabberwocky on a glorious, “frabjous” day – intra-textually decodeable as the mythical messiah from the Underland scrolls and extra-textually recognizable as a Jeanne d’Arc-ish feminist action hero-like re-embodiment of Tenniel’s original illustration to Carroll’s novel. Like in other adaptations where Carroll’s novel appears as a book the filmic protagonist reads, the Burton-movie’s ‘real life’ heroine, Victorian, bourgeois, teenage Alice identifies with the imaginary alterego (the mythical knight/Tenniel picture) of the title-character of the Carroll-novel, and thus turns the (image)textual original ‘truly fictionalised’ within the filmic revision’s factualised alternate reality. Via a simultaneous homage and destabilization, the adaptation’s fictional reality earns a primacy over the original’s. Yet, simultaneously, the original (image)text invoked in the moving-image-adaptation also owns a certain indubitable master-mythological veracity that allows for the reinforcement of the credibility of revisioned fantasy’s reality status. Alice’s first ocular self-(mis)-recognition on witnessing the scrolls is reinforced by a performative speech act upon the final triumphant fight with the Jabberwock. The fully armed and armored Alice, besides authentically embodying and enacting the Tenniel illustration’s knight, also reads herself out loud into the story. She states in her voice-over narration, as if by a magical incantation, that her capacity and willingness to believe impossible things (as many as six, before breakfast; and even impossibilities as her being the saviour of Wonderland4) allows her to defeat the monster.

Figure 13.

(Again monstrosity here might refer just as much to the flesh-and-blood dragon as the nonsensical (il)logic of Wonderland.) Thus, she calls to life Wonderland on verbal-visual-auditory planes (actualizes the image-text-sound interaction), and affirms fictionality’s credibility and her own agency as a character, reader and author of her own story.

Paradoxically, the oscillation between imaginative willingness and reluctance initiated by the above intermedial shifts and fusions does not stop here. Alice’s intratextual mythologisation via Carroll’s and Tenniel’s image-textual evidence attests her predestination to heroism in fantasy realms she finds increasingly credible, but it will eventually result in her rejecting her belonging to the daily reality of Victorian England on her return, arguing that its bourgeois customs and conventions are impossible phantasmagorias she is unwilling to believe in or identify with. She rejects her era’s social codes of conduct as communal fantasies in the name of a proto-feminist pragmatism for the sake of a private mythology that idealistically allows her to follow/realize dreams of her own. In fact this fantasist anti-conventionalism already lurks there in the original Tenniel illustration that mockingly dresses up the nonsensical monster to be slain in a neat bourgeois waistcoat, as if to highlight the inseparability and perhaps interdependence of fantasizing and realism.

Strangely it is the lack of imaginativeness, even an imaginative resistance or reluctance that serves the ground for criticism in Burton’s spectacular movie. Uncharacteristically of the director renown for his quirky dark fantasies, his cinematic revisiting of the Alice-theme renounces of the wildest Carrollian phantasmagorias and nonsensical language philosophical speculations’ crazily calculated cacophonic unpredictability for the sake of a more coherent, didactic, even moralizing Bildungs-plotline. The simplistic finale of American children’s writer Linda Woolverton’s script celebrates girl-power’s dubious feminist empowerment strangely combined with entrepreneurial, pro-capitalist, colonising might and even a touch of Oedipal desire. Instead of being married off as a properly feminized Victorian object-of-exchange to her wealthy, pedantic suitor and instead of being willing to get fully lost in Wonderland’s fantastic realm as a rebellious fantasist, pragmatic Alice decides to step in the footsteps of her father, undertake family business and embark on oceanic trade routes towards China, a locus of exoticized, wondrous otherness, and further financially motivated adventures with the trading company that becomes the scriptwriter’s rather down-to-earth “metaphor for life” (Woolverton in Callaghan 2011). Despite Alice’s farewell “futterwackenjig” dance, an homage to the Mad Hatter, rationality seems to triumph over fantasy, as Burton’s protagonist is endowed with the domesticated feminism of the latest Disney princesses, Mulan, Belle or Rapunzel, who fight for their dreams while carefully respecting the stereotypical structural frames of the Disneyfied fairy tale (Disney 1991, 1998, 2011). (These are the teleological coming-of-age-plotline enhanced by funny sidekicks who reinforce the hero-antihero dualism by a distinction between laughing with or at characters and the neat narrative closure organised by patriarchal family romance, heteronormativity and a submission or containment of potential feminine agency.)

The reviews published in The Guardian, after the film’s release in March 2010, agreed on the adaptation’s being a “curiously flat,” “lifeless reimagining” with a “mediocre script,” (French 2010) “tepid dialogue,” “weak characterisation,” and “a dull, weightless fantasy world” (Bradshaw 2010). However, despite the fact that Burton was nearly unanimously regarded to “fail as a spellbinding movie tale-teller” (French 2010) even the harshest critics had to admit somewhat reluctantly that the “brilliant visual art,” the “highly distinctive,” (Bradshaw 2010) “vivid imagery,” the “dazzling, gothic set design, and lavish costumes” make the film “seducing [like a] peacock spreading its fantastic plumage,” “a pleasure to regard” and one must “gawp at the sensual beauty of it all” (Brooks and Barnes 2010).

Figure 14.

I believe that it is precisely this stunning visuality (Fig. 14) that lets enchantment finally win over unimaginativeness in Burton’s movie too. Although the counter-fantasy realm’s clearly postmodernist, self-reflective metanarrativity quite likely distance, defamiliarize and destabilize the alternate universe’s fictional realities via the multiple mise-en-abymes of images and texts I analysed above, imaginative willingness still prevails as an overall effect. Even if Alice is initially unable to remember and unwilling to believe in her childhood’s Wonderland devalued as Underland, and even if after having completed her mission in the realm down the rabbit-hole, she abandons it to accomplish the frame-story’s rationalistic project of feminist and colonial empowerment, her skepticism is counterbalanced by the spectators’ ravishment by the photorealistic simulation of wonders through the 3D CGI (computer-generated imagery) cinematic technique, that enables enchantment to predominate disenchantment. In place of the subtle literary, philosophical, socio-critical allusions taking place on the Carrollian original’s discursive plane, the filmic adaptation’s amazing ambiguity is gained from its visual powers.

Nevertheless, the adaptation is not so far from the original as we would first presume: for the celebration of the 3D CGI spectacular visual style’s supremacy over the plotline-contents’ dramaturgic sophistication can be regarded as the cinematic equivalent of literary nonsense’s celebration of “sound’s supremacy over sense,” a stress on the how instead of the what of sense-making, Lecercle finds decisive of the genre (2-3). The means are still prioritized to the end, the form still predominates the content, only transmitted to a different medium, shifting the emphasis from the verbal to the visual representational mode.

In Burton’s movie, the Mad Hatter’s eery reciting of the Jabberwocky-poem is a fine example for the intermedial conjoining of verbal and visual nonsense.

The mesmerizingly monotonous monologue the Hatter half-mumbles to himself in an incomprehensible gibberish, a maniac voice and a strange Scottish accent (to which he switches upon the splitting of his personality before his mad fits) allows rhyme, rhythm and repetition, and the material surplus of his incarnated voice predominate meaning. Besides meta-representational realizations of the misbehaviour of language and the ambiguity of (verbal and/or visual) common-sense, this foregrounding of the sensory, lived, embodied experience of discourse, the corporeal, physical nature of the signifying activity, Brooks calls the somatization of semiosis (8), (whereby the sounds and shapes of words may produce decisive surplus-meanings, as the Kristevan theory on revolutionary poeticity (see 1984) also argues) is the other major technique of the nonsensification of sense.

However, these verbal (or even the oral-auditory) effects are not necessarily the ones moviegoers will associate with the Burtonian Wonderland. In Burton, the nonsensical enchantment is primarily not of verbal origin, it does not restrictively result from the Hatter’s demented discourse – emerging only in this particular episode of the film – his recurring, unanswerable riddles, or the perplexing undecipherability of the Jabberwocky poem. These serve only to complement and maximalize his insane, psychedelic looks, his puzzling image that constitutes the peak of ocular nonsensification – and that has become, accordingly, in trailers, movie posters, and advertisements, the trademark of this latest improbable world of Alice.

Figure 15.

The Mad Hatter is a computer graphically distorted, digitally manipulated live action character whose unnaturally exaggerated facial features, enormously enlarged, impossibly electric green eyes, crazy clownish flaming hairstyle, strange twisted movements and unnatural mask-like or over-exaggerated mimics – equally reminiscent of puppets, silent-movie stars, or demented maniacs – clearly defamiliarize his humanity, by courtesy of the CGI technology. Thus, the Hatter’s looks and speech both reach a familiar unfamiliarity and an unfamiliar familiarity, and an overall uncanny nonsensical effect. Paradoxically, however, the Hatter’s positive persona as a helping figure who protects the humanistic values against the Red Queen’s ruthless terror also invites to a spectatorial identification, and thus, to the internalization of spectacular otherness.

The Burtonian imagery appeals to our visual literacy and collective cultural imagination in a calculated cacophonic way: the Hatter is not only a CGI-de/formed double of Burton’s favourite actor, Johnny Depp – it is him, but unrecognizable – but by cinéphiles he is also recognized as a fusion of Depp’s earlier roles, intertextually melting Edward Scissorhands, Willy Wonka, Jack Sparrow, J. M. Barrie and Sweeney Todd into the Hatter’s character. The end-result is a proliferating postmodernist patchwork, a camp collage of visual nonsense. Certain scenes of fantasy-fragments and filmic crossovers pay a tribute to previous visual adaptations ranging from Dali’s surrealistic phantasmagorias, Annie Leibovitz’s Wonderland fashion photos and Disney’s sweet children’s classic to the eery Victorian paintings of Arthur Rackham, an Alice-illustrator succeeding to Tenniel in the 1907 edition, whose one-time home Burton uses today as his office. Other scenes consistently use extra- and inter-(image)textual allusions and borrowings to invite a multifocal interpretive perspective combining referentiality with symbolicity to resist fixed meanings.

Alice combines Tenniel’s chivalric Childe, dragon-slayer St George, visionary St Anthony and heroic Joan of Arc and, in a somewhat baffling-way, earns her name from Charles Kingsley (though spelt as Alice Kinsleigh), author of Victorian science-inspired fantasy best-seller, the visionary The Water Babies: A Fairy Tale for a Land Baby (1863), while she is equally associated with the film-theme-song’s performer, Avril Lavigne, pop-icon of teenage rebellion, who plays an Alice-alterego in her music video. While one of Alice’s side-kicks, the mighty dormouse warrior resembles the Chronicles of Narnia’s Reepicheep, the Red Queen mockingly recalls Queen Elizabeth from the Blackadder series and Bette Davis’s Elizabeth I, the White Queen is a mixture of star-chef Nigella’s dark double who cooks with human body parts such as ButterFingers, of a punk spirited Debbie Harry, an ethereal Dan Flavin, a glamourous and graceful Greta Garbo, and Glinda the Good Witch on hallucinogens – as Burton affirms in a Daily Telegraph interview (Salisbury 2010). The pseudo-rationalistic framing is familiar from the Wizard of Oz, and an old, “black-and-white photo of a family having tea during the Second World War with London, dishevelled, in the background” (Burton in Salisbury 2010) is also among the major inspirations of the macabre Underland atmosphere.

Accordingly, we might say that both literary and visual nonsense require recipients, along with the fictionally implied reader/spectator Alice, to exercise an inventive interpretive creativity, to make self-corrections, re-readings/re-visions and playful deconstructions, while exchanging primary (normal, literal, denotative, ‘original’) meanings for supplementary (less obvious, figurative, poetic, intertextual/intermedial) ones or vice versa, succeeding to Humpty Dumptian claims/realizations of “that’s not what I meant” (Carroll 221, 224). Interestingly, as Michael Hancher highlights, Alice’s strange world preserves its reassuring familiarity on a visual plane both for Victorian readers who have been granted “frequent previews of Wonderland” in Tenniel’s well-known political cartoons drawn for Punch, and also for contemporary audiences overexposed to the Alice-iconography in novel consumer-oriented contexts’ postmodern repurposings, ranging from IBM advertisements to sexy Halloween costumes (29) which, mingled with vague childhood memories of the Alice-tales, constitute a simultaneously pleasing and troubling déjà-vu experience.

In Wonderland’s CGI realm, everything looks like a very vivid-surrealistic-dream version of our own mundane reality where nothing is exactly as it seems. The protagonist experiences spectacular shrinkings and growings but remains the same Alice, whose self-identity is nevertheless constantly doubted by everyone around her. She looks like Alice, but she cannot be truly her since “she seems to have lost her muchness” (Burton 2010). This nonsensical line also amptly portrays the moviegoers’ bewilderment upon their inability to precisely locate what is ‘wrong’ (out of order/out of focus) with Wonderland’s CGI characters despite their striking lifelikeness. The computer digitally manipulated live action characters, these half-human, half-animation figures feel real – “it looks like they have a soul” as the director says in the DVD’s extras (Burton “Featurette” 2010) – but spectators, like the filmic Alice, do not precisely know what sense to make out of them. In this respect their CGI effects’ visual nonsense functions in a very similar way to the Jabberwocky poem’s literary nonsense: “they somehow seem to fill heads with ideas – only one doesn’t exactly know what they are!” (Carroll 156) More specifically, the CGI animated live action hybrid characters – fusing human and technologically enhanced features – recall the Carrollian portmanteaux, neologisms melting two distinct word-entities into one new, undecidable meaning, hailing the logic of uncertainty. In fact, literary nonsense can be defined as any discursive claim, written text or act of symbolisation that resembles, and is decoded as language, as meaningful communication, yet its intelligibility becomes dubious, defamiliarised along with our conventional representational and interpretive strategies meant to make sense of it.

Consequently, I wish to argue here that the Carrollian literary nonsense’s foregrounding of the malfunctioning of language is cinematically translated into the troubling of transparency of visual meaning and representation, as Burton creates visual nonsense by exploiting multiple levels the fundamental ambiguity of the 3D, computer graphically animated/live action fantasy filmic image(text). (1) Firstly, the conjoining of live action reality’s footage and computer graphic simulation creates a hybrid alternate fantasy-world in which the numerous digital effects – the movie was shot in 90% on green screen, with a footage of 2000 digital shots (Salisbury 2010) – distort the actors’ actual physical appearances (like the size of the Queen’s enormous head, the height of alternatively tiny or giant Alice, or the Hatter’s impossibly electric green eyes). Live action CGI animation’s sophisticated means also provide to the fully animated fantastic characters of the human personalities of the real-life actors who lend them their voices (e.g.: the Cheshire Cat gains Stephen Fry’s iconic sarcastic persona though Fry never appears on screen in person), while through multiplications of digitally manipulated real-life characters (like the twins Tweedle Dum and Tweedle Dee or the ‘clone-army’ of identical playing cards) copies of copies are created – and thus enter into a total play with our fantasizing faculties, by questioning the reality status and the very origin of the credible original. (2) Secondly, our imaginative confusion is further augmented by a perplexing conjoining of the marvellously horroristic fairy tale-fantasy genre’s radical anti-realism with the computer technology’s hyper-photo-realism, that is coupled with the contrast of the historical veracity of the story-frame’s authentic Victorian setting and the embedded fantasy-story’s Carroll-inspired, nonsensical, once-upon-a-time and far-far-away neverwhere. (3) Thirdly, with the 3D CGI technology the spectatorial gaze is increasingly controlled by the new (mixed-)media’s visual literacy that precisely directs our attention, trains us where and how to look, but we also witness a strange destabilization as on-lookers are deprived of a neat separation and a safe distancing of the (im)possibilities of imagination through the metamorphic blurring of make-believe fantasy and our world/reality/life. (4) Fourthly, 3D CGI technology allows for a total immersion in the filmic alternate fantasy-reality and a full identification with its imaginary creatures, events and (il)logic, since it simultaneously enchants and stupefies both adults and children by visibly rendering/attributing an ‘actual’ life-like verisimilitude to the Impossible (Wonderland) ‘that has never been,’ turning the ‘Unimaginable’ visible, feasible and credible via a computer/digital-technologically simulated blurring of the make-believe fantastic and the real/world/life.

Yet, simultaneously, as a major technological means of Burton’s visual nonsense 3D CGI also incites metatextual recognitions concerning the misbehaviour of representation, shifting the focus from the what on the how of image/sense-making, while foregrounding the unnaturally all-too-natural and visionarily over-fantastificated ‘texture of images.’ The defamiliarization and denaturalization of images, and our alienation from them – paradoxically conjoined with the above mentioned blissfully immersive identificatory mechanisms – is nearly necessarily provoked by the act of putting on the special glasses which allow moviegoers to see the 3D effects, while accompanying their spectatorial pleasure with a physical weight reminiscent of the constructedness of images, texts and stories. This might perfectly illustrate what Mitchell means when he argues that the essence of the pictorial turn is not a “return to naive mimesis” but a “postlinguistic, postsemiotic rediscovery of the picture as a complex interplay of visuality, apparatus, institutions, discourse, bodies, and figurality” (16).

Thus, the tension between imaginative willingness and reluctance is never fully resolved – neither for Burton and Woolverton’s Alice whose adventures “validate Wonderland as real [memory and not the dream she had believed it to be] just as she is also moving into adulthood and leaving it behind,” nor for the spectators who accompany her on her “dual journey” (Callaghan 2011). Cunningly enough, the question here is not whether Wonderland exists (according to the filmic scenario, it certainly does, regardless of all beliefs), but whether one chooses to believe in it, and whether one chooses to live (in) it. In a playfully nonsensical yet strictly logical manner, the affirmative answer to the former dilemma does not contradict the refusal of the latter option. It is the very possibility of choosing (or rejecting) fantasy that makes reality tolerable.

With regards to the coexistence of imaginativeness and incredulity there is a significant parallel between Carroll’s Victorian and Burton’s postmodernist era. According to a recurring nonsensical guideline to Wonderland one can and should believe impossible things – with practice believe as many as six impossible things before breakfast as Carroll’s Queen does and recommends Alice to do (Carroll 210). “The only way to achieve the impossible is to believe it to be possible,” Burton adds somewhat didactically in a recurring line equally uttered by Alice’s father soothing his daughter after her nightmare, the Mad Hatter pondering about the interconnectedness of reality and illusion, and eventually Alice triumphing over the Jabberwock. This line also reflects the epistemological crisis shared by late 19th century Victorian and the post-millenial era. In Carroll’s times, the bourgeois public was stupefied by reading morning newspapers’ accounts of impossibilities (Wullschläger 43-44), like the invention of photography, the mass print-production of popular novels, the building of the British Museum, an enormous storehouse of pictures, or the opening of the spectacular Crystal Palace world fair.

Burton’s generation, on its turn, first incredulously gapes at, then gradually gets used to visual impossibilities, such as witnessing worldwide live-real-time-broadcasts or computer simulated, photo-realistic reconstructions of History-making catastrophes on televised and online emissions, or circumscribing identities on the basis of photo-shopped, speculative ‘doubles’ of celebrities, internet avatars, and inventively compiled Facebook profiles. Apart from the loss of faith in the transparency of images and texts, the two eras are identical, as Henry Jenkins and David Thornburn argue, in their resulting self-conscious awareness of change and apocalyptic rhetoric simultaneously envisioning “a technological utopia where emerging communication systems foster participatory democracy” and a culture of chaos, instability and corruption through the commodification of information by technological changes annihilating more reliable old media (x). According to Jenkins and Thornburn, the transitions witnessed by the Victorian era – amply recorded in John Stuart Mill’s “The Spirit of the Age” – sufficiently attest that there is no need to fear the possibly radically innovative (media)changes brought about by the digital revolution. As Deborah L Spar claims, “technological change follows a cycle of innovation and experimentation, commercialization and diffusion, creative anarchy and institutionalization” (in Jenkins and Thornburn x). During mediatransition, the new system rarely ever obliterates essentially its predecessor to fully take on its function while consigning the older form to waste and oblivion. New media are more likely to coexist, often reinventing, rejuvenating, and mutually inspiring one another.

Burton’s 3D CGI filmic extravaganza inspired by Carroll’s and Tenniel’s classic image-text instead of obliterating the original, rather stimulated booksales of ‘the novel behind the blockbuster movie’ – just as absurdly as the Twilight novel and movie popularized Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet as the love-story that inspired the first volume of vampire Edward and human Bella’s teenage gothic romance saga, that brought new readership for the Bard – due to his recommendation by one-time fan-fiction writer Stephenie Meyer. The postmodern Alice is marked by an increasing complexity of co-authorship: it is Burton’s re/vision of Woolverton’s re/reading of Tenniel’s view of Carroll’s Alice. The inevitable proliferation and destabilization of the image-text is illustrated by the fact that besides the numerous visual (book)guides to the film, a novelization of Burton’s movie has been published in a movie tie-in book-edition by T. T. Sutherland entitled Disney: Alice in Wonderland (Based on the motion picture directed by Tim Burton), that was meant to textually promote the film’s visibility but also stands as a work in its own right. In an endless process of image-textual recycling we move from novel to illustration to script to moving image to movie tie-in novelization.

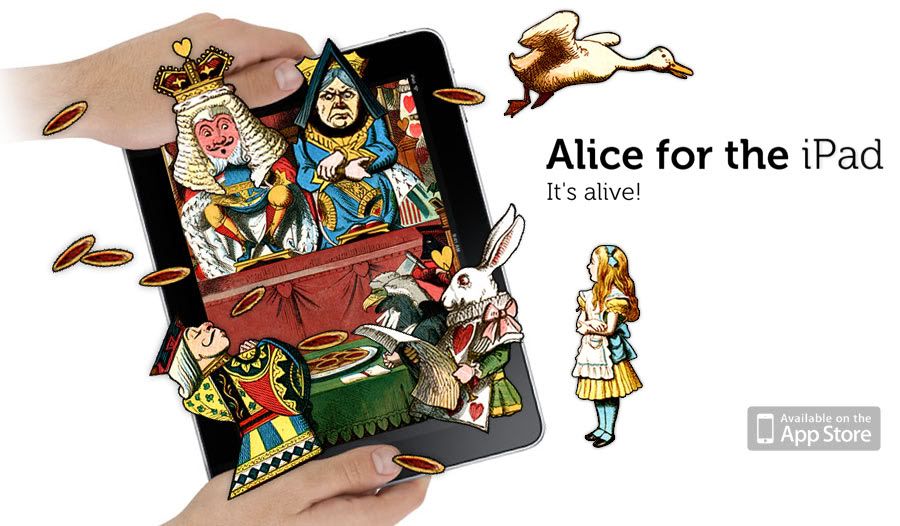

Figure 16.

The multi/intermediality of these (sub)versions peaks in Alice in Wonderland digitally remastered for the iPad (Fig.16), whereby the “full screen physics modelling” of an “amazing selection of animated scenes” bring the classic Carroll-text and Tenniel-illustrations “to real life” as you can touch, shake and tilt your iPad to make Alice grow or shrink, to bounce the White Rabbit’s pocket watch, collide with the Dodo, or swim through the Pool of Tears. (Alice for the iPad Demo 2010)

Here, the embodied experience of moving along with the image/text enables readers’ creative, corporeal cooperation in the ludic re/production of nonsense. In a Carrollian vein, meaning-de/formation turns into play. This technologically enhanced nonsensification is further increased in the sequel, Alice in New York for the iPad2, a special celebration of the 140th anniversary of Through the Looking Glass, first published in 1871, advertised as “the incredible and the never-before-seen turned real.” (Alice in New York for the iPad 2011)

This proves that the intermedial shifts accompanying the transmission of word to image, or vice versa, quite likely result in a literal animation of any text, even if interpretive attitudes might need to be adjusted to the media in question, in order to be able to appreciate ‘original’ literary classics’ (visual) adaptations which seem less efficient at first sight. One might also argue that the question concerning the similarity and difference of visual and verbal media (of dis/enchantment) is just as unanswerable as the Mad Hatter’s famous riddle attempting a comparison of the raven and the writing desk in Carroll’s original nonsensical wordplay. Tellingly, the riddle “Why is a raven like a writing desk?” (Carroll 73) was intended to remain unresolved in the book but later triggered numerous answers. Some solutions were based on verbal play: most famously the answer “Because Poe wrote on both,” Aldous Huxley’s witty response “Because there’s a b in both, and because there’s an n in neither,” and Carroll’s own afterthought in the preface to the 1896 edition, “Because it can produce a few notes, tho they are very flat; and it is nevar put with the wrong end in front!” where “never” was misspelt with an “a” to read as “raven” backwards, and was often hypercorrected by proofreaders ignoring the pun (Cohen in Carroll 75, Susina 16-17). Other solutions were based on visual play: for Jan Susina the tall, black-cloaked reverend Dodgson leaning over his writing-desk in his sombre clerical outfit reminds of a raven, while the quick action of his hands compiling hundreds of letters, riddles, and language games resemble “the motion of flapping wings” (18); thus, the fantasy world he creates allows his imagination to fly free.

This nonsensical riddle makes us aware of the paradoxical tension between the simultaneous necessity of misinterpretations and the impossibility of meaninglessness, as well as the necessary overlapping of word- and image-play. Ambiguities prevail, but we can conclude that the realization of visuality and verbality as mutually enriching components of the same image-text-fusion, and a common basis of Carroll’s original and Burton’s revisioned fantasies, illuminates readers by shedding light on inevitably conjoint intermedial strategies of making (up) (non)sense in/of any work of art.

Works Cited

- Adamson, Andrew and Vicky Jenson, dir. 2001. Shrek. Written by William Steig and Ted Elliott. Dreamworks.

- “A gyerekfilm félelmetes világa.” 2011. Prizma filmművészeti folyóirat. Tematikus szám. 1.

- Alice for the iPad Demo. 2010. Access: 30/08/2011. Available: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gew68Qj5kxw

- Alice in New York for the iPad. 2011. Access: 30/08/2011. Available: http://www.AliceNY.com

- Bower, Dallas, dir. 1949. Alice in Wonderland. Written by Edward Eliscu, Albert E. Lewin and Henry Myers. Lou Bunin Productions.

- Bradshaw, Peter. 2010. “Review on Alice in Wonderland.” The Guardian, 04/03. Access: 30/08/2011. Available: http://www.guardian.co.uk/film/2010/mar/04/alice-in-wonderland-review

- Brooker, Will. 2005. Alice’s Adventures. Lewis Carroll in Popular Culture. New York-London: Continuum.

- Brooks, Peter. 1993. Body Work. Objects of Desire in Modern Narrative. Cambridge: Harvard UP.

- Brooks, Xan and Henry Barnes. 2010. “Review on Alice in Wonderland.” The Guardian, 05/03. Access: 30/08/2011. Available: http://www.guardian.co.uk/film/video/2010/mar/05/tim-burton-alice-in-wonderland?INTCMP=ILCNETTXT3487

- Burton, Tim, dir. 2010. Alice in Wonderland. Written by Linda Woolverton. Walt Disney Pictures.

- ——. 2010. “Finding Alice Featurette.” Alice in Wonderland. DVD.

- Callaghan, Dylan. 2011. “Wonder Woman. An Interview with Alice in Wonderland’s Linda Woolverton.” Writers Guild of America, West. Access: 11/11/2011. Available: http://www.wga.org/content/default.aspx?id=4004

- Carroll, Lewis. 2001. The Annotated Alice. The Definitive Edition. Martin Gardner ed. London: Penguin.

- Cartmell, Deborah, I.Q. Hunter, Heidi Kaye, and Imelda Whelenan. 2000. Classics in Film and Fiction. London: Pluto Press.

- Cohen, Morton and Edward Wakeling, eds. 2003. Lewis Carroll and His Illustrators: Collaborations and Correspondence, 1865-1898. New York: Cornell University Press.

- Collingwood, Stuart Dodgson. 2008. The Life and Letters of Lewis Carroll. Charleston: BiblioBazaar.

- Curtis, Neil, ed 2010. The Pictorial Turn. London: Routledge.

- Del Toro, Guillermo, dir. 2006. Pan’s Labyrinth. Written by Guillermo del Toro. Estudios Picasso and Warner Bros.

- Disney, Walt, prod. 1951. Alice in Wonderland. Directed by Clyde Geronimi et al. Written by Winston Hibler et al. Walt Disney Studios.

- ——. 1959. Sleeping Beauty. Directed by Clyde Geronimi et al. Written by Erdman Penner et al. Walt Disney Studios.

- ——. 1977. The Many Adventures of Winnie the Pooh. Directed by Wolfgang Reitherman and John Lounsbery. Written by Larry Clemmons et al. Walt Disney Studios.

- ——. 1991. Beauty and the Beast. Directed by Gary Trousdale and Kirk Wise. Written by Linda Woolverton. Walt Disney Studios.

- ——. 1998. Mulan. Directed by Tony Bancroft and Gary Cook. Written by Rita Hsiao et al. Walt Disney Studios.

- ——. 2011. Tangled. Directed by Nathan Greno and Byron Howard. Written by Dan Fogelman. Walt Disney Animation Studios.

- Ennis, Mary Louise. 2000. “Alice in Wonderland.” In Jack Zipes ed. The Oxford Companion to Fairy Tales. The Western Fairy Tale Tradition from Medieval to Modern. Oxford, New York: Oxford University Press, 10-12.

- French, Philip. 2010. “Review on Alice in Wonderland.” The Guardian, 07/03. Access: 30/08/2011. Available: http://www.guardian.co.uk/film/2010/mar/07/alice-in-wonderland-review

- Genette, Gérard. 1997. Palimpsests: Literature in the Second Degree. Translated by Channa Newman and Claude Doubinsky. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press.

- Gilliam, Terry, dir. 2005. Tideland. Written by Tony Grisoni and Terry Gilliam. Recorded Picture Company.

- Green, Roger Lancelyn. 1997. “Alice.” (1960) In Robert Phillips ed. Aspects of Alice. New York: Vintage Books, Random House, 13-39.

- Guiliano, Edward, ed. 1982. Lewis Carroll: A Celebration. Essays on the Occasion of the 150th Anniversary of the Birth of Charles Lutwidge Dodgson. New York: Clarkson Potter.

- Hancher, Michael. 1985. The Tenniel Illustrations to the “Alice” Books. Columbus: Ohio State University Press.

- ——. 1982. “Punch and Alice: Through Tenniel’s Looking Glass.” In Edward Guiliano ed. Lewis Carroll: A Celebration Essays on the Occasion of the 150th Anniversary of Charles Lutwidge Dodgson. New York: Potter, 26-49.

- Hepworth, Cecil and Percy Stow, dir. 1903. Alice in Wonderland. Written by Cecil Hepworth. American Mutoscope and Biograph Company, Edison Manifacturing Company and Kleine Optical Company.

- Jenkins, Henry and David Thorburn, eds. 2003. Rethinking Media Change. The Aesthetics of Transition. Cambridge: MIT Press.

- Kérchy, Anna, ed. 2011. Postmodern Reinterpretations of Fairy Tales. How Applying New Methods Generates New Meanings. Lewiston, Lampeter: The Edwin Mellen Press.

- ——. 2011. “Nonsensical Disenchantment and Imaginative Reluctance in Postmodern Rewritings of Lewis Carroll’s Alice Tales.” In Catriona Fay McAra and David Calvin eds. Anti-Tales. The Uses of Disenchantment. Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 62-75.

- Kelly, Richard. 1982. “”If you don’t know what a Gryphon is”: Text and Illustration in Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland.” In Edward Guiliano ed. Lewis Carroll: A Celebration. New York: Clarkson Potter, 52-62.

- Kristeva, Julia. 1984. Revolution in Poetic Language. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Lecercle, Jean-Jacques. 1994. Philosophy of Nonsense. The Intuitions of Victorian Nonsense Literature. New York: Routledge.

- Leibovitz, Annie. 2003. “Alice in Wonderland Fashion Editorial.” Vogue USA, December. Access: 07/03/2012. Available: http://trendland.net/alice-in-wonderland-by-annie-leibovitz/#

- Lull, Janis. 1982. “The Appliance of Art: The Carroll-Tenniel Collaboration in Through the Looking Glass.” In Edward Guiliano ed. Lewis Carroll: A Celebration. New York: Clarkson Potter, 91-97.

- McAra, Catriona Fay and David Calvin, eds. 2011. Anti-Tales. The Uses of Disenchantment. Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

- McCallum, Robyn and John Stephens. 2000. “Film and Fairy Tales.” In Jack Zipes ed. The Oxford Companion to Fairy Tales. The Western Fairy Tale Tradition from Medieval to Modern. Oxford, New York: Oxford University Press, 160-164.

- McGee, American. 2000. American McGee’s Alice. Rogue Entertainment. Electronic Arts.

- McLeod, Norman Z., dir. 1933. Alice in Wonderland. Written by Joseph L. Mankiewicz. Paramount Pictures.

- Mitchell, W.J.T. 1995. Picture Turn. Essays on Verbal and Visual Representation. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Peabody, Richard, ed. 2005. Alice Redux. New Stories of Alice, Lewis and Wonderland. Washington D.C.: Paycock Press.

- Phillips, Robert, ed. 1997. Aspects of Alice. Lewis Carroll’s Dreamchild as Seen Through the Critics’ Looking-Glasses. New York: Vintage Books, Random House.

- Pilinovsky, Helen. 2011. “Salon des Fées. Cyber Salon: Re-Coding the Commodified Fairy Tale.” In Anna Kérchy ed. Postmodern Reinterpretations of Fairy Tales. How Applying New Methods Generates New Meanings. Lewiston, Lampeter: The Edwin Mellen Press, 17-33.

- Ryder, Christopher. 2009. “Alice in Wonderland – Press Conference with Tim Burton.” Collider.com. July 23. Access: 30/08/2011. Available: http://www.collider.com/2009/07/23/alice-in-wonderland-press-conference-with-tim-burton/

- Ray, Gordon Norton. 1991. The Illustrator and the Book in England from 1790 to 1914. New York: Dover.

- Ross, Deborah. 2000. “Home by Tea-time. Fear of Imagination in Disney’s Alice in Wonderland.” In Deborah Cartmell et al. eds. Classics in Film and Fiction. London: Pluto Press, 207-229.

- Salisbury, Mark. 2010. “Tim Burton and Johnny Depp Interview for Alice in Wonderland.” The Daily Telegraph. 02.15. Access: 28/03/2011. Available: http://www.telegraph.co.uk/culture/film/starsandstories/7205720/Tim-Burton-and-Johnny-Depp-interview-for-Alice-In-Wonderland.html

- Sigler, Carolyn, ed. 1997. Alternative Alices: Visions and Revisions of Lewis Carroll’s Alice Books. Kentucky: The University Press of Kentucky.

- Spar, Debora L. 2001. Ruling the Waves: Cycles of Discovery, Chaos, and Wealth from the Compass to the Internet. New York: Harcourt.

- Staples, Terry. 2000. “Alice in Wonderland, Film Versions.” In Jack Zipes ed. The Oxford Companion to Fairy Tales. The Western Fairy Tale Tradition from Medieval to Modern. Oxford, New York: Oxford University Press, 12-13.

- Street, Douglas, ed. 1984. Children’s Novels and the Movies. New York: Ungar Film Library Press.

- Susina, Jan. 2001. “‘Why is a Raven like a Writing-Desk?’: The Play of Letters in Lewis Carroll’s Alice Books.” Children’s Literature Association Quarterly, 26. 1., Spring, 15-21.

- Sutherland, T. T. 2010. Disney: Alice in Wonderland (Based on the motion picture directed by Tim Burton). New York: Disney Press.

- Szabó, Noémi. 2011. “Moralitásjáték – a gyerekfilm és a társadalmi elvárások.” Prizma, 1.5., 8-14.

- Wanning Harries, Elizabeth. 2003. Twice Upon a Time. Women Writers and the History of the Fairy Tale. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Weaver, Warren. 2006. Alice in Many Tongues. The Translations of Alice in Wonderland. Mansfield Centre: Martino Publishing.

- Willing, Nick, dir. 2009. Alice. Written by Nick Willing. Original television mini-series for Syfy channel, 2 episodes, 180 minutes, Original run: 6-7/12.

- Wojcik-Andrews, Ian. 2000. The Children’s Film. New York: Garland.

- Wullschläger, Jackie. 1995. “Lewis Carroll: The Child as Muse.” In Jackie Wullschläger. Inventing Wonderland: The Lives and Fantasies of Lewis Carroll, Edward Lear, J.M. Barrie, Kenneth Grahame, and A.A. Milne. New York: Simon and Schuster, 29-65.

- Zipes, Jack. 1994. Fairy Tale as Myth/ Myth as Fairy Tale. Lexington: UP of Kentucky.

- ——, ed. 2000. The Oxford Companion to Fairy Tales. The Western Fairy Tale Tradition from Medieval to Modern. Oxford, New York: Oxford University Press.

List of Illustrations

- Figure 0: The first filmic adaptation of Alice. Cecil Hepworth and Percy Stow’s silent movie: Alice in Wonderland, 1903. Available: http://www.examiner.com/images/blog/EXID3770/images/alice-chased-by-the-cards.jpg

- Figure 1: Walt Disney’s Alice in Wonderland, 1951. Available: http://www.elisanet.fi/mlang/kuvat/alicedis.jpg

- Figure 2: American McGee’s Alice, a third-person action game released for PC in 2000. Available: http://www.game-ost.ru/static/covers_games/1946_234505.jpg

- Figure 3: Hello Kitty’s Alice in Wonderland. Available: http://2.bp.blogspot.com/_n-hm9gvEHbk/S1NigBIkmpI/AAAAAAAAH9M/MQkMxqgQ69c/s400/Kitty_Alice.jpg

- Figure 4: Tim Burton’s Alice in Wonderland, 2010. Available: http://blazingminds.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2010/03/alice-in-wonderland-poster.jpg

- Figure 5: Su Blackwell. Book Sculpture. “A Mad Tea Party.” Available: http://www.sublackwell.co.uk/wp-content/gallery/sculptures/2007-alice-a-mad-tea-party.jpg

- Figure 6: Jeliza Rose reading Alice in Wonderland in Terry Gilliam’s Tideland. Available: http://1.fwcdn.pl/ph/45/26/154526/135240.1.jpg?l=1239196318000

- Figure 7: Lewis Carroll’s manuscript and drawing of Alice. Available: http://www.radford.edu/~mbrady/Lewis_Carroll_Alice.jpg

- Figure 8: John Tenniel’s illustration to Alice. Available: http://3.bp.blogspot.com/-ZelWCAyOgQg/TYv8nIdpe2I/AAAAAAAADPE/T6u374wdfes/s1600/alice-with-bottle.jpg

- Figure 9: Syfy’s Channel’s Jabberwock. Available: http://media.sfx.co.uk/files/2011/01/240111jabberwocky11.jpg

- Figure 10: Tenniel’s Jabberwoock. Available: http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/e/e3/TheJabberwocky.jpg

- Figure 11: Alice meets Humpty Dumpty on Tenniel’s illustration. Available: http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/e/e3/TheJabberwocky.jpg

- Figure 12: Tim Burton’s Calendrical Compendium to Wonderland with an homage to Tenniel’s Jabberwock. Alice in Wonderland Touring Display. Available: http://farm3.static.flickr.com/2763/4419886271_1a07ca5ddd.jpg

- Figure 13: Alice ready to slay the Jabberwock in Burton. Available: http://www.cbc.ca/gfx/images/arts/photos/2010/03/04/arts-alice-wonderland-584.jpg

- Figure 14: Stunning visuality in Burton 3D CGI vision of Alice. Available: http://images2.fanpop.com/image/photos/9100000/Alice-in-Wonderland-tim-burton-9171481-1024-513.jpg

- Figure 15: Burton’s Mad Hatter. Available: http://s.ecrater.com/stores/60130/4b6cc21e05ed1_60130n.jpg

- Figure 16: Alice in Wonderland digitally remastered for the iPad. Available: http://www.apppli.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/04/Alice-for-Ipad1.jpg

Notes

1 I wish to express my gratitude to Professor Zoltán Vajda for encouraging me to explore how media change influences the nonsensical effect and the recipients’ (dis)enchantment. ↩

2 This was the second manuscript. The first, unillustrated manuscript copy was finished in February 1863. The rowing expedition with the Liddell girls took place on July 4, 1862. (Weaver 19) ↩

3 Carroll’s seminal nonsense poem is entitled The Jabberwocky, while its undefinable, monstrous protagonist is called the Jabberwock. ↩

4 Alice’s magical incantation-like monologue in Burton is the following: “I try to believe in as many as six impossible things before breakfast. Count them, Alice. One, there are drinks that make you shrink. Two, there are foods that make you grow. Three, animals can talk. Four, cats can disappear. Five, there is a place called Underland. Six, I can slay the Jabberwocky.” ↩

Copyright (c) 2012 Anna Kérchy

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.