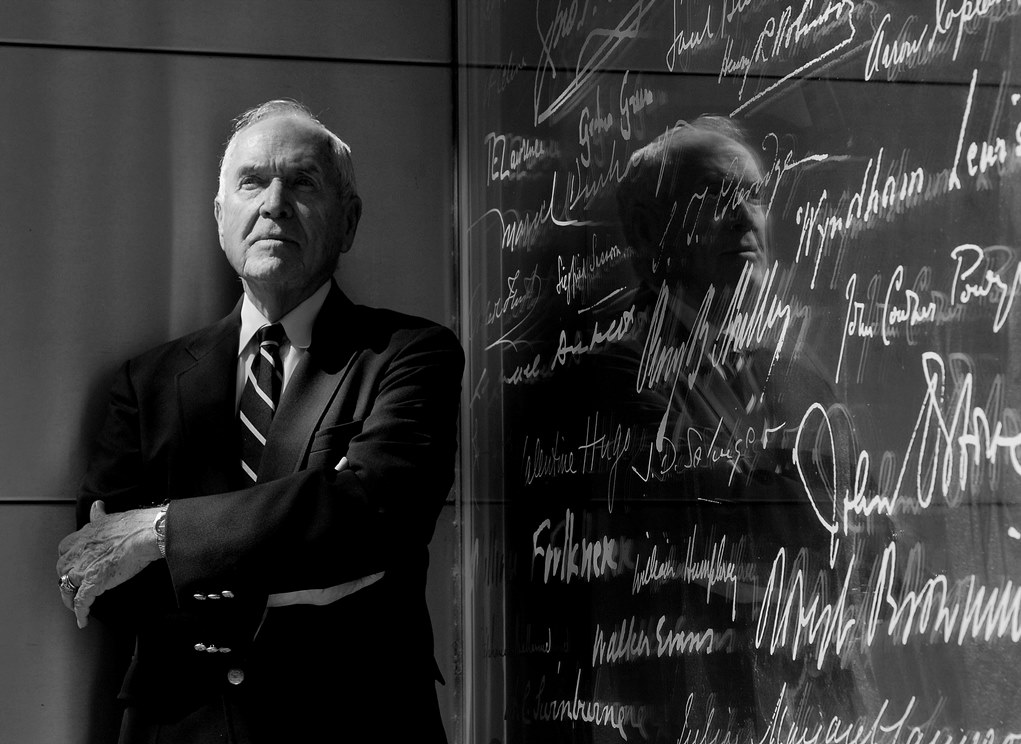

Rolando Hinojosa-Smith is a prolific Chicano writer, author of numerous novels and essays. His books include Dear Rafe (1985), Becky and her Friends (1990), We Happy Few (2006) among others and are usually referred to as the Klail City Death Trip Series. The series of novels tell the story of the inhabitants of the fictional Belken County. The variety of local color characters resemble the natives of the Lower Rio Grande Valley, where Hinojosa was born in 1929. His Mexican and American family roots equipped him with fluent Spanish and English, while his surroundings provided him inspiration for his fiction. His series of novels capture the local color of the Lower Rio Grande Valley and fill the fictional Belken County, which is sometimes paralleled to William Faulkner’s Yoknapatawpha County. Hinojosa had witnessed the Korean War and recorded his observations of―the often grim―everyday camp life in his book Korean Love Songs (1978).

He keeps a busy schedule besides writing: has been teaching, editing, attending conferences, and being a relentless mentor for aspiring writers on his writing seminars. In 2003 he was among the jurors of the Pulitzer fiction committee, not long ago he also co-edited the Norton Antology of Latino Literature (2010), and published a collection of short stories and essays in A Voice of My Own: Essays and Stories (2011). He is currently the Ellen Clayton Garwood professor in the English Department at the University of Texas at Austin, where he teaches both literature and creative writing.

In the summer of 2011, Hinojosa was among the guest lecturers of the Graz University Summer School to give readings from his works, and most importantly, to teach the tricks and tips of good fiction writing through his creative writing seminar. He shared loads of practical wisdom including a recurring quote by Faulkner to “read, read, read”. Between classes, he was glad to pause and converse with the students and tell anecdotes about his surprisingly eventful life. On one such occasion he shared the story of writing a novel while cruising aboard a freighter all the way from California to Japan, Korea, and China.

As a former Summer School participant I asked him to talk about his writing method, his career, his recent literary projects and publications since the Summer School, and he did not mind sharing a few anecdotes about the fascinating life of a writer.

Q: First of all, what drove you to fiction-writing?

RHS: At that time, I was the Modern Language Department Chairman at Texas A & I University (now Texas A & M at Kingsville) when an undergraduate from the Valley came to see me and showed me an interview with Tomás Rivera as well as a published short story. The student said that Tomás had won the Quinto Sol Prize for his novel, written in Spanish; the Q.S. was founded at the University of California at Berkeley. I read the material and it was very good. Not much later, I read the novel . . . y no se lo tragó la tierra——first translated as And the Earth Did Not Part, and later, . . . And The Earth Did Not Devour Him. Later, after Tomás died, I did a rendition of it and titled it This Migrant Earth because the subject was the migrant farm laboring class. I said to myself, “well, there’s a literary journal that publishes in Spanish.” I decided to write a short story (“Por esas cosas que pasan”) which later became a part of the first novel, Estampas del Valle which, some ten years later I wrote in English as The Valley. After Tomás’s prize, the following year, Rudolfo Anaya of New Mexico was awarded the prize for his novel Bless Me, Ultima; I won it the following year, l973, for Estampas. After that came the Casa de las Américas Prize, (El premio Casa de las Américas) in Havana, in l976 for Klail City y sus alrededores; years later, I published it in English as Klail City with Arte Público Press; years later, Bilingual Review/Press published it as El condado de Belken (Belken County). They chose that name to not conflict with Klail City.

Q: Did these works influence the communities of the Valley?

RHS: Influence? I doubt if my work has influenced the Valley; I hope it has influenced youngsters to write, not necessarily what I write about, but about their lives, their times. I don’t know how many people read my stuff; if some do, it’s most likely college students from the two universities in the Valley and from South Texas College, a two-year school that prepares the students for further undergraduate work. I was honored by STC in the fall of 2011, but I was unable to attend. A shame, but there was an earlier commitment.

Q: What do you think about the tendency of the younger “Valley” generations reading more in English?

RHS: Reading is a process which leads to assimilation and acculturation, and Spanish takes a back seat; it makes sense that English should predominate, that’s why the students enroll in higher education. I usually take a census in my classes among Texas Mexicans about their fluency and that’s the case: to succeed, they must master English. If there’s monolingual grandmother in the home, the students may learn Spanish that way, but only up to a point, as anyone can imagine. In my family’s case, we spoke both languages daily, and I was lucky, as the youngest of five, to have learned from my parents and my brothers and sisters; added to which, our reading material was also bilingual, and thus, bicultural. I was fortunate, because my mother was raised in a ranch and the majority of the population was Texas Mexican. Her Spanish was perfect in reading, writing, and speaking. Her English was as well, but this goes without saying. My father was also bicultural and bilingual. They read individually and to each other, and this was a model to follow; I come from a family of readers and teachers: my maternal grandmother, Martha Phillips taught school as did my mother; of the five of us, three boys and two girls, four of us went into the teaching profession. I’ve been told by friends and students alike that if they started to say something in one language, they had to stick to it. There was no such proscription in our household. We mixed and matched, it didn’t matter.

Q: Was this situation unique to your family?

RHS: Yes, in many ways. Many of our classmates were half and halfers, that is, half Texas Mexican and half Anglo because of the intermarriage by Texas Mexican women with the Anglo soldiers who were stationed in Mercedes. My mother was raised in the Valley bilingually and biculturally; of the half and halfers, we were the only one with an Anglo mother.

Q: You also translate your works from Spanish to English.

RHS: Yes, I do; when I write something in Spanish, I’ll translate it to English. I didn’t at first. When Estampas del Valle was printed, in ‘73, I think, someone else did the translation. Later in l983, I translated Estampas and called it The Valley. It went into several printings. When I write something in English, I no longer translate it into Spanish. Why? Because most of the market now reads English. It’s a new generation, and it’s no longer fluent enough to read, speak, or to write in Spanish. Spanish won’t disappear, of course, but it’s not as common as it was in the preceding generations. Arte Público Press published A Voice of My Own, Essays and Stories November 2011; two of the stories are in Spanish with an English translation. That same month, APP reprinted Partners in Crime, a procedural novel of l984 which showed the violence along the border due to the dope trade. No national newspaper wrote about the violence the Mexican side of the border was going through. In ‘98, APP published Ask a Policeman which showed a rise in the violence, but once again no national papers wrote about it. Now, in the 21st century, U.S. newspapers carry stories just about every day; one statistic showed that 47,000 murders were committed in 2011 in Mexico due to fighting between the various dope cartels. I just remembered something: I didn’t translate Claros varones de Belken either; I must have been engaged in something that took my time. As it was, however, I had to make many corrections because although the translator was fluent in Spanish, there was a decided weakness in English usage; translations are difficult and what this translator did was to translate literally. That doesn’t work.

Q: Do you apply any “additional creativity” whenever you translate your works?

RHS: Whenever I’m to translate from Spanish to English, I always stop to think of the what but, just as importantly, of the how I’m going to translate what is said by the characters or what is in the narration. If I used an adage, an axiom, a proverb, a maxim, etc., there are always equivalents but as said previously, one mustn’t translate literally, word for word, because that doesn’t work. One has to analyze what is in the original to make the point with an equivalent adage or axiom; if there’s none, there must be something close to the original, and I’ll go with that. What one looks for is meaning. Here’s an example, I’ve read Quijote any number of times, wrote my Master’s thesis on the adages, etcetera, and have read any number of translations; the most recent are Burton Raffel’s and Edith Grossman’s. I bought Tom Lathrops’s last week; he’s the editor of the Bulletin of Cervantes Studies. I’ve read the introduction, and it’s first rate. One of my favorite translators is the Canadian Leila Vennevitz who translated Heinrich Böll’s work; she’s my favorite because Böll is one my favorite writers as are Faulkner, Flannery O’Connor, Anthony Powell, Eudora Welty, and many others.

Q: So the English versions are more like adaptations? Could we put it that way?

RHS: I think it’s a rendition more than a translation, but there is translation, of course. So, it’s a rendering of a society, a linguistic sect with another society (English-Spanish/Spanish-English). It’s presenting two societies who live in close, at times, intimate proximity.

Q: Speaking of creativity, you also teach creative writing. What do you consider the most relevant, either practical or theoretical, aspects that you feel important to share with students?

RHS: I teach creative writing at my home institution along with other courses, but in creative writing, I stress reading; we began the class sponsored by Graz University stressing reading. Why? Because reading is imperative; one begins to read, enjoys it, is captivated by it, and one day, begins to write, to create, based, of course, on reading. Some people think that imagination is everything. It isn’t; imagination can only take one so far; one needs to read and to learn from reading and living one’s life and learning how others live. One can’t know everyone in any given country, but solid reading gives one the opportunity to see how others live. What to read? Fiction helps, of course, but there’s also the history of a people that’s important. How could I, how could anyone, know of the many and varied relationships of the southern states without the aid of Faulkner and those writers who took a long, serious look at the black and white societies in small towns and in metropolitan areas. Observation helps as does listening. But, after everything, reading and reading carefully will open all manner of doors toward imagination which plays a part but not the most salient part in creativity. Writing, then, has to do with experience and experiences; there’s no getting around it.

Q: Is there any other practical wisdom?

RHS: Yes. I advise beginning writers to use clear, everyday language. To try not to show off how much one knows. An experienced reader will see through the phoniness of using high- toned language when none is called for. Writing is not about self-aggrandizement, that’s for amateurs. A professional has a story to tell, and learning how to tell it without resorting to pointing to oneself is an important part of writing.

Q: Do you get feedback from your students of creative writing?

RHS: Yes, I do; most of them write to tell me of some recent publication of theirs, of being hired to teach creative writing, and how they remember the class, and so on.

Q: Do you remember them?

RHS: Yes, most of all, the creative writers; due, in some part, to the size of the classes, 12 to 14 to 16. Last spring, 2011, produced some of the best writers I’ve had. They were hard-working, serious about their reading and writing, and that made it a pleasure to walk in every class meeting knowing it would be an exciting class.

Q: How do you assess a class? What do you look for when you teach a class?

RHS: By their willingness to work, to contribute to class discussion, to criticize their own writing, and by their seriousness of purpose. Many students shop for classes during the first week, the serious ones stay, the shoppers see that the class will call for more work than they thought or were willing to do. Assessment is not difficult; if you don’t have to correct usage, punctuation, mechanics, capitalization, and grammar, you’ve won a healthy part of the battle. There are only three elements to prose fiction: setting/background, plot, and characterization; if they attend and to that, a third of the grade is taken care of. I look for enthusiasm, the willingness to comment on their fellow students’ work and on their own, and, reporting on what they’ve been reading lately, and why. When they write in class, one side will comment on the work; the second group will comment, offer advice, and so on; the other side, then, writes and the process is repeated. Writing begins in class with 20 minutes, then 25, 30, and and 35. Since they all have spiral notebooks, at the end of the semester, they’ll realize that what they have is a treasure trove of material of their own and something they can enlarge, amend, add to, and so on. Also, I always want students to become their own critics. It’s self-criticism and this is always to the good. There is no getting around it, one has to be able to criticize one’s work; a writer cannot afford to be lenient hence close reading is called for. Writing is hard, and it calls for honesty.

Q: Have you influenced younger writers?

RHS: I think I have from the emails I receive. When invited to read down there, it’s usually the professors read and teach parts of the series. The ones who hang back are the students who want to write; they come with the usual questions: how do you start a novel or a short story, where do you get your ideas, what are you reading now, what is your favorite reading now, and so on. What pleases me is that they want to write because this translates into reading, the vital element for anyone who wants to write.

Q: Should writers distance themselves from their own writing?

RHS: Yes. You can’t fall in love with what you write; if you do, that leads to disaster, to poor writing, and you have no one to blame but yourself.

Q: Talking about critics, you were one of the judges for the Pulitzer Prize in 2003.

RHS: Yes, I was one of three critics for the Pulitzer Prize; it was hard work, and one read novels by known writers and, up to that point, by unknown writers. The three of us agreed that if a writer didn’t engage us by 25 pages, that writer wasn’t going anywhere. We were given 10 months to read 456 novels, and I finished a good number of them, but didn’t vote for them. Why? Because I thought they weren’t up to Pulitzer material. The ones that we selected for first, second, and third prize were praised later by the literary critics. We weren’t reading for them, however. We were reading for ourselves and for future readers.

Q: You are a teacher, a critic, and you are also an editor.

RHS: I think every writer falls in those three categories. One, at times, edits for friends or for former students. One offers advice but one shouldn’t force one’s friends to follow it. I edit my own work and I will delete a word, a sentence, a paragraph, a page, if necessary, if I feel that the writing is or was sloppy. Perhaps I was tired and didn’t know it, but, when one is wide awake, poor writing jumps at you, hence the severe lopping off the material. There’s no getting around it.

Q: And you were also a member of the editorial staff for the Norton Anthology of Latino Literature.

RHS: Yes, thirteen years of that. I, and the others, worked and looked at the anthology as a service, as something that would last and contribute to this country’s literature. With the advent of email, this meant we could work together, each in a different field, of course. I would check on proper titles, the date of publication, the number of reprints, and much more; the reason? It’s a textbook and one’s name will appear on it, and no one, but us, is the responsible party, hence the drive toward accuracy. This anthology, some 2900 pages, took the five of us 13 years to gather, write, edit, etc. Last December, Norton said the work was doing very well.

Q: Do you see a correlation with the Anthology and the emergence of Inter-American studies?

RHS: There may be one, but I’ve not thought about it. The chief reason is that Latino Literature, as many are now calling it, is now included in departments of English, Spanish, Latino Studies, etc. at some of the most prestigious U.S. universities: Harvard, Yale, Cornell, Berkeley, Stanford, and U.T., as well as other universities. That was the additional battle, to get the literature in universities.

Q: Your latest publication is called A Voice of My Own.

RHS: Yes, it’s out as well as a reprint of Partners in Crime (l984), a police procedural showing the violence in Mexico and how it affected the Valley and the border area. I followed this with Ask a Policeman (l998), and it too dealt with the violence along the border. It took the U.S. and almost all of its citizens to realize that the violence also affected this country. A Voice of My Own, Essays and Stories is a compilation of essays I’ve been publishing since the late ‘70s to the recent times; as for the short stories, two of which are in Spanish, these have been published here and there.

Q: What topics are addressed in these essays?

RHS: The first essay is called This Writer’s Sense of Place; it gives my background as a borderer and how having been born in a small farming community on the Texas-Tamaulipas border, in a bilingual/bicultural setting, and its history helped me to become a writer. The next one, Living on the River, concerns the cultural and linguistic environment, the make up of the land, the Valley as the last of the Spanish colonies, the biracial population, and, once again, how this, too, helped me to write. The others have to do with the development of Mexican American literature as a widening of the definition of what constitutes American literature as another addition to American literature. The short stories do not form part of The Klail City Death Trip series, however, they further identify the setting and the background of my fiction.

Q: How do you spend your time when you want a break from writing, editing, or assessing?

RHS: Working, traveling, seeing members of my family, and catching up on my reading. I write some, of course, and keep up my correspondence with friends and colleagues, writing letters of recommendation, and preparing for the coming semester. I also take advantage to do readings in conferences or when I am invited to do so by other universities. In brief, I don’t take time off since I consider traveling and coming to Graz or reading in Europe, (Germany, the Netherlands, Spain, etc.) a vacation and the chance to see old friends in those and other countries.

Q: Getting back to writing: how come you wrote the manuscript of We Happy Few while traveling on a ship?

RHS: Since childhood, I’ve wanted to travel on a freighter, not one of those so-called cruise ships with two or three thousand people. My youngest daughter found a company in California that books trips on freighters which are now called container ships. There was room for eight passengers on the Lykes Eagle, owned by Canadian Pacific, but, luckily I was the only passenger. The crew were Indian from South Asia. Fine cooking, of course. I brought eight paperbacks, old friends, as I call books I’ve read before: Graham Greene, Joseph Conrad, Heinrich Böll, and so on. My room was spacious, a private toilet, a good-sized writing desk, a comfortable bed, and the freedom to go to the bridge, day or night. I also watched the on-loading and the off-loading of the merchandise, the many, many birds that rested atop of the water, with stops in Tokyo, Quingdao, Xiamen, Hong Kong, and Tsinjin. In brief, 35 days and nights. Perfect for writing, and I did so. No computer this time; I went back to how I started: writing by hand.

Q: For you, writing comes hand in hand with a relaxed lifestyle.

RHS: Yes. I have very few friends, but they’re close, and I’ll watch the Super Bowl with them; it’s usually the same people, friends and colleagues from the university. I don’t party much; I’m not antisocial but I enjoy being by myself. I also have a son, two daughters, a lovely daughter-in-law, and two grandsons. E-mail affords me the luxury of keeping up with them. Walking is also a pleasure for it gives me time to think things out. I enjoy movies and some, but only some, television. I’m a widower, I have a job, some friends, my health, and the time. Writing and teaching, then, take much of that time, but those are pleasures. Why? Because I do what I want to do when I want to do it; at 84 years of age, that too is a luxury.

Q: Would you talk about your current work?

RHS: I’ve been writing and publishing; this March, Editorial Xordica (Zaragoza, Spain) published Estampas del Valle to celebrate the novel’s fortieth year of existence. This spring semester I’m teaching one course in Fiction Writing and a Signature course; the latter is for first-year university students and its titled “WAR”. We’ve read Crane’s The Red Badge of Courage, and Robert Graves’ Goodbye to All That among others. I’ve decided to cut down on campus visits this spring semester and accepted only one: the University of Houston, which was an overnight visit. So, aside from teaching, what else have I done? “Read. Read. Read” (Faulkner). I’ve been reading for enjoyment and pleasure, as always.

Q: Thank you for the talk.

Copyright (c) 2013 Gábor Tillman

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.