Introduction

Today a presidential candidate in the United States cannot get ahead without being present on social media. Let it be Facebook, Twitter, Tumblr, or all three, the candidates have to be able to reach audiences that are more likely to be glued to their smartphones than the television screen: “The newest mass medium, the Internet, has quickly taken its place as the fastest-growing vehicle for advertising” (Fellow 327). This was not always so, there was an evolution in mediums. As there was a clear shift from radio to television there was also a need for media to expand. The study of media history is to research how new mediums were initially exploited before developing to adhere to public demand.

Whilst discussing media history, the research done by students moves into digital archives, covering tapes, videos, photos and recordings available. These sources live on because the evolution of media requires a constant link between past and present, since media always evolves when the previous mediums are no longer capable of satisfying their given audience. When presidential candidates spoke on the radio, they had to make sure to speak clearly and in an articulate matter; then on television, body language became of the utmost importance as visuals took over. The Internet has both visual and written surfaces. For the former the same laws apply as with the ones to television; for the latter, the laws of journalism apply: correct usage of grammar and spelling as well as political correctness. Upon examining the evolution of media in relation to the political history of the United States in the line of milestones represented by than Franklin D. Roosevelt’s Fireside Chats, Dwight D. Eisenhower’s first televised political ads, and John and Jackie Kennedy’s life in the everyday press (Fellow 321) one name is bound to be encountered over and over, that of Richard Milhous Nixon.

This President is of remarkable importance because his active political career, stretching from 1947 to 1974, is filled with digital testimonies that serve as a time machine for students. The research of this paper focuses on challenging a quote by Marshall McLuhan, professor and prominent figure of media theory, claiming that “the more the data banks record about each one of us, the less we exist” (Buurman 238), as according to my research Nixon is very much alive thanks to the immense material available on him. During the second half of the twentieth century “the power of journalists, especially broadcast journalists, clashed with the power of the presidency in what could be called ‘an era of deception’” (Fellow 331). He himself is also a wonderful example of surrendering to change in order to adhere to what the masses wished to see. The President had completely different approaches to campaigning in 1960 than he did in 1968, showcasing, as this paper will demonstrate, that political background for a candidate to win an election was no longer the winning factor. Recalling the past three U.S. elections, there is a clear indication that the candidate’s knowledge and use of a medium is what gets the most votes.

To a certain extent oral history re-emerges and evolves, as well, since it is no longer handed down, but it can be recalled verbatim thanks to recordings. The procedure of impeachment, for example, changed significantly in the United States once digital evidence was introduced: “When the transcripts of the White House tapes were released, it turned out that [John] Dean’s memory had rewritten the scene” (Ernst 2).It is important to keep in mind that the evolution of the media is not confined to the invention of television, or the fact that mass media evolved into social media. Before starting to discuss the topic, or rather, the man this paper focuses on, the term media in the title of the essay has to be explained. In this paper, media will refer to the press’ as well as the television news outlets’ involvement in Richard Nixon’s career. Starting with an analysis of the campaigns, both his vice-presidential and his presidential ticket, the term media will refer to the press as an active entity that helped to bring about Nixon’s resignation. This paper focuses on the evolution of media, more precisely on multimedia as opposed to the press. The scope of this paper does not allow full discussion of the relationship between Nixon and the press during all of the thirty years to be covered in the essay. However, the major changes the press did experience in this period will be discussed in the paper in detail. Unfortunately the impact of media is hard to define when one is not present and is simply researching past events. However, both the Kennedy vs. Nixon debate and the Frost vs. Nixon interview are among the most well-known milestones of media history, and thus it is easier to get an impression of the incredible amount of influence they had and still have today (Katz and Dayan 188).

For the research of this paper, transcripts of recordings, videos, and finally photographs are used to demonstrate the impact that media had on political history and how, in particular, one politician was shaped by the media. The paper will be divided into two major chapters that first detail Nixon’s career as a vice-president, followed by his term in office as President of the United States, and end with his interview with David Frost. Each chapter will detail those encounters Nixon had with the media that shaped him as a candidate and contributed to shaping history.

1. The Road to the White House

The politician, Richard M. Nixon was a man who fought long and hard to get into the Oval Office and was on the headlines of both printed press and television news several times. Thus, when discussing media history one is bound to bump into Richard Nixon at some of the biggest milestones. Although it was not until 1968 that he got the Presidential seat, his political career began far sooner, and his presence in everyday media helped him in becoming an expert of the press, but not an expert of presenting himself according to the press’ wishes. This was something he had to learn from Kennedy, who “set out to become the first movie-star politician” (Barnes 51). For Nixon, Kennedy represented everything he hated growing up: someone who had a life where the sky was the limit. Nixon worked very hard to achieve his political ambitions, and even if he was beaten at first, he rose again from the ashes to claim his throne. The following chapter analyzes this process, along with his capability of coping with the ways mass media was changing audiences’ interests and perceptions of political life. There will also be a comparison drawn between the United States’ stances in the Cold War in 1960 as opposed to 1968.

1.1 Becoming Vice-president: Nixon No. 1

The young Richard, eventually the running mate of Dwight D. Eisenhower, was a Senator from California who had experience as a politician but was not a leading man. Nixon was previously a congressman for California between 1947 and 1950, finally a senator, a position from which he resigned purposefully to run for the Vice-presidential seat. He became known for a the indictment of Alger Hiss, a State Department official whom Nixon was determined to expose as a communist (Riechmann). The case was covered thoroughly by the press and Nixon became more famous around the country as he also advanced in his political career. His rise to power was started by his presence on the Republican ticket, and despite his active years as a successful politician, being a representative or a senator alone would not have gotten him ahead. His use of the media for manipulation and campaigning was more visible once in office. He was a good choice for second in command, but he would not become adapt to be the right candidate for the presidency until his battle against Vice-president Hubert Humphrey in 1968. Although a politician’s relationship with the media changes massively when they step into office, being a vice-president for eight years Nixon shared the same spotlight as the President and for that this period is of extreme importance.

Eisenhower, approached by both parties as a potential nominee, identified as a Republican and decided to run. Nixon came into the picture because Republicans sought somebody who was “young, vigorous, ready to learn, and of good reputation” (“The Vice-president”) and at that time, he checked all the boxes. Nobody could foresee that during the campaign, when Nixon had already been chosen as Eisenhower’s running mate, the press would attack the future vice-president with allegations of pocketing money designated for the campaign. This means that the Watergate scandal was not the first time that Nixon had been accused of acting improperly under the eyes of the law. There was a clear claim that “campaign donors were buying influence” from him “by providing him with a secret cash fund for his personal expenses” (“The Vice-president”). Nixon decided to set the record straight since his position as vice-president on the Eisenhower ticket was being compromised; he did so through a medium that was uncharted territory at the time.

The vice-presidential candidate was the first one to use television to talk directly to the American people for no other than political purposes. He did so in a television special that he himself called “the Fund speech”, but which is more widely known as “the Checkers speech”, with a mocking purpose, named after a special dog he mentioned in it (Black 261).It is considered “one of the twentieth century’s most significant political speeches” (“Richard M. Nixon”) (Picture 1). In the end, Eisenhower did not drop him from the ticket, although he had intended to: Eisenhower’s staff called Nixon just before the address and instructed him to resign his position on the ticket at the end it on the air. The Republican Party was under immense pressure as TheWashington Post and the New York Herald Tribune participated actively in demanding Nixon’s resignation from the ticket. If the allegations were proven to be true, then that would have come as a grave handicap for Eisenhower because it would have meant that “his running mate exemplifies the unethical conduct that [the Presidential candidate] is denouncing” (Black 228). However, Nixon did not resign, but left the decision up to the Republican National Committee instead and asked the people to voice their opinions via telegrams (Allen and Nixon 92). The overwhelmingly positive feedback Nixon received left no other choice for Eisenhower but to head for the November elections with his team as it was.

Picture 1: Screenshot of the Checkers Speech. 1952. (Youtube. 25 Nov. 2016.)

The Checkers speech was unique not only because it was unprecedented; it was also unique because of its content. Nixon decided to give a complete financial history of all the money he had ever possessed, of “everything I earned, everything I spent, everything I owe” (“Checkers Speech”). Not only did he emphasize that the funds were not secret and gave an audit of all the known and legal purchases that were made to aid the campaign, but also went on to give a list of sums, interests and rates at which he received money and then paid it back (“The Vice-president” and “Checkers Speech”). He emphasized that he worked hard for every penny he and his wife had ever earned before and after the war. During the speech Nixon did address one personal issue: “We did get something as a gift, after the election” he said. His wife Pat mentioned in an interview that their two girls wanted a dog. A man from Texas sent them a package just before they left for Washington, and inside they found a cocker spaniel who his daughter, Tricia, named Checkers. Nixon finished the sentence saying that “regardless of what they say about it, we’re gonna keep it” (“Checkers Speech”).

His tone was quite academic, and it did not resemble the kindness that Roosevelt possessed in his Fireside chats, or with which other Presidents would address the nation at the end of the 20th century (Freedman 20). Nixon used this occasion to set the record straight, appear as an honest man who wanted to get respect from his voters, not to be their friend. This is one of the occasions where Nixon could have opened up more, and could have created a bond with the audience. In a way he did– when he spoke about his little girl and the dog that they fell in love with immediately – but to a very limited extent. It is believed, however, that it was that bit of humanity that led the voters to sympathize with him. Not wanting, or not being able to open up on a more personal level is one of the biggest differences between him and John F. Kennedy, Ronald Reagan, Bill Clinton and even Barack Obama today. Nixon used this occasion to make things “perfectly clear”, a sentence he uttered so often during his campaign speeches that it became a national joke in the end (20). The presence of television, a new medium, tilted the scales and made it possible for Nixon to stay on the ticket. The same effect could have hardly been achieved if his tax returns had been simply released, since there was need for him to defend himself and convince the voters of his honesty. To compare with the latest election in the United States: Nixon was going to be forced to quit just the race for the vice-presidency, whilst in 2016 the candidate who got elected refused to release his tax returns (“Trump Owes Us His Tax Returns”). Since not even the media was able to get the candidate to comply, this unfortunately implies that once again media is just a passive viewer instead of the active participant it was during the sixties and the seventies.

What preceded and also followed the Checkers speech was young Richard’s fierce campaign for the Republican Party. At the time of choosing a VP it was the Democratic nominee who had better numbers in California. However, young Richard, born in Yorba Linda, CA, proved a favorable choice from a geographic point of view (Black 188). He gave speeches, attended fundraisers and did a lot more campaigning on scene than Eisenhower. This was not only in the years before getting the Republican nominee to the Oval office, but was also typical of Nixon when re-election came four years later: “Early in the new (presidential) year, Nixon resumed his strenuous speaking schedule, more than thirty such events in the first four months” (191). Not only did Eisenhower not wish to tour the country, but his health got in the way a lot of times. This was another reason why Nixon’s active nature made him a perfect choice the second time around.

Looking back at the years of his vice-presidency, Nixon did make a difference. He was truly a part of the administration and not just somebody who could be alerted if the President were to fall ill or, in the worst case, die in office. As a matter of fact, Eisenhower had a coronary attack in 1955, followed by an operation in 1956, making his health the biggest issue of the re-election, as Democrats reminded voters that they might be voting for Nixon’s presidency. Events escalated when Eisenhower got a stroke in 1957 and he drafted a letter that stated the terms and powers of the vice-president while he was incapacitated ("Richard Nixon"). This letter, or in other words, this formality was overruled by the 20thAmendment, which stipulated the chain of succession. There was a strict definition of the passing of power in cases of illness or other factors that would incapacitate the chief in command temporarily (“Amendment XX”).

Richard Nixon possessed every favorable characteristic for a vice-president: he was both a congressman and a senator before heading to the White House, and as such, he was one of the most experienced men in Eisenhower’s team (“Richard M. Nixon”). The office of the vice-president became more prestigious and a place to strive for, as the VP became an active member of the given administration (“The Vice-president”), but this was also because Nixon was not the kind of politician who would silently stand by. He looked for challenges and when he was given orders, he executed them properly. Eisenhower and Nixon both had a significant although different military past behind them, but this allowed for the latter to adhere and respect the chain of command. Their collaboration was, however, questioned by the press when Eisenhower set out to run for re-election. Any doubts raised on whether or not Nixon would remain on the ticket can be credited to the press (“The Vice-president”).

It was not unprecedented that a president chose a new VP when they ran for office for a second term. In other cases the VP would have a job waiting for them in the cabinet or they received an outside offer: Nixon was offered a job at two major law firms, in Los Angeles and New York as well. He had previously said that his wife Pat did not like Washington that much and if he was kicked off the ticket, they would move (Black 328). Eisenhower had awkward conversations about this matter as the press had printed rumors of a new vice-president and even asked the president about those rumors at a press conference, where Eisenhower said the following: “If anyone ever has the effrontery to come in and urge me to dump anybody that I respect as I do Vice-president Nixon, there will be more commotion around my office than you have noticed yet” (325). President Eisenhower was particularly mad at James Reston from The New York Times as he implied that it was the president’s administration that wanted to force Nixon out. For the Republican Party’s point of view, they would have come off as weak if Nixon had left. If young Richard had left on his own, it would have weakened the chances of re-election, while Nixon being forced out would have meant the admission of fear of his growing power on Eisenhower’s side (328). Nixon then, taking matters into his own hands as he did with the Checkers speech, did not wait for the President to decide whether he could stay on the ticket. Nixon approached the President in the Oval office and told him: “Mr. President, I would be honored to continue as Vice-president under you”, and it was this kind of sheer communication that kept him on the ticket once again. He was an essential part of Eisenhower’s second term of office. When Eisenhower-Nixon was first voted into the White House most of the campaign’s success could be accredited to Nixon. He was very quick on his feet, sometimes a bully to the Democrats and was overall of an aggressive nature. During the re-election of 1956 he was asked not to campaign in such a manner again. However, it seemed that the vice-president’s aggressive approach to campaigning could again bring success for the Republicans. Once Nixon had put on the boxing gloves again he helped to deliver an easy re-election for his party (“Richard M. Nixon”).

Although Nixon was not present in the media on an everyday basis as far as domestic policy was concerned, he did become an “ambassador” for the United States and as such appeared in international news all the time. He was sent on several missions abroad in a crucial era of the Cold War. His diplomatic ability and standing strong during a troublesome time made him somewhat “cool” and famous on an international level (“The Vice-president”). His first trips took him to Asia, South Korea and Japan, which would give Americans the impression that he was an expert in Asian affairs. He was more of an “ambassador” sent around to deliver Eisenhower’s will. In 1956 he traveled to Europe, Austria to meet with Hungarian refugees and then a year later he traveled to Africa (“Richard M. Nixon”). The idea of Richard Nixon as a hero back home was born after a trip to South America, from which he believed he would not return safely or that he might be killed (“The Vice-President”). During his trip he visited Peru people chanted “Go Home Nixon!”; in Venezuela he was spat on, leaving the military of the country as well as that of the United States to help rescue him. He arrived home to the States, where thousands of Americans gathered at the airport to welcome him, including the President, and for weeks people praised the bravery with which he faced the Venezuelan people with his wife Pat (“Richard M. Nixon”).

A testament to the active role of the media is its ability to reinforce the status of leaders (Katz and Dayna 201), and so Nixon made history once again when he became the first American official to address the Soviet Union in a live broadcast, following the famous “Kitchen Debate” with Nikita Khrushchev, which “was front-page news in the United States the next day”. Set up in a kitchen set modeled after American ones the two politicians had a heated argument over capitalism and communism. As it was with many Cold War battles, “there was no clear winner–except perhaps for the U.S. media, which had a field day with the dramatic encounter” (“Nixon and Khrushchev”).

Despite having changed the idea of a vice-president on a political scale, and having traveled more than any other American official would up to that point, visiting fifty-four countries, Nixon wanted more. He said himself that it “is not possible in politics for a Vice-president to chart out his own course” (“Richard M. Nixon” and Black 326), so the next logical step was running for presidency. Back when Eisenhower ran for a second term he did admit that Nixon was the perfect man for the presidency, with this justifying keeping him on the ticket, as well as giving young Richard the moral endorsement he sought, but had not received yet (Black 335).During his time as vice-president Nixon never overstepped his bounds. Even when Eisenhower was sick he made sure not to “take too much control as it would arouse fears of a power grab by an overly ambitious understudy”. He would go to senators himself and he would work from his office on Capitol Hill as any other elected official (“Richard M. Nixon”).

In 1958 Nixon intervened and campaigned for senators as well as congressman since the House was changing and the scale was tipping toward the Democratic side. Finally, his involvement resulted in party leaders throughout the nation owing him a debt that he collected when he ran against Kennedy (“Richard M. Nixon”). Even if on paper Nixon was the best candidate available, unfortunately for him that sense of security blinded him as he came face to face with an opponent he had underestimated.

1.2 Nixon vs. Kennedy

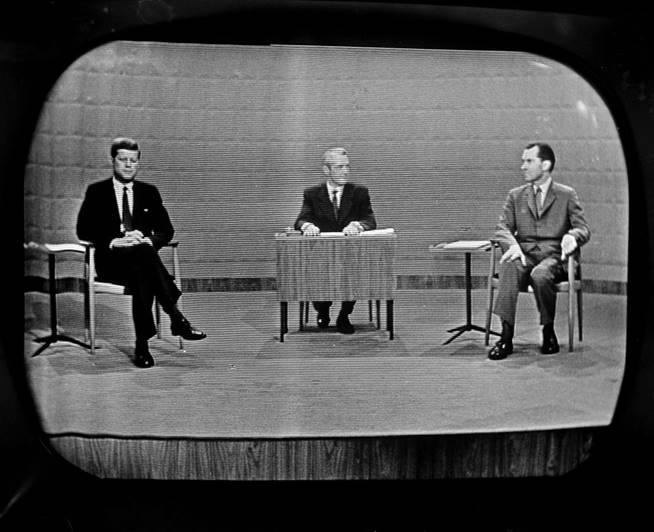

Decades after the first televised presidential debate between Kennedy and Nixon, aired on September 26th, 1960 (Picture 2), it is still regarded as a milestone from both a historical and a media historical point of view. The importance of this debate might be overlooked today, with over 500 channels and portals, websites and live streaming but back in 1960 the influence of visual mediums was untested. This debate was crucial in the election campaign of both candidates: the Checkers speech was viewed by almost sixty million people and it was the debate that broke that record audience (“Richard M. Nixon”).

Picture 2: Democrat Sen. John Kennedy, left, and Republican Richard Nixon, right, as they debated campaign issues at a Chicago television studio on Sept. 26, 1960. Moderator Howard K. Smith is at desk in center.(Digital image. US NEWS. Accessed16 Dec. 2016.)

Television debates were still uncharted territory, but there was much interest in making sure such an event would occur, firstly for the Kennedy campaign. The Democratic campaign had limited funds, and they had asked the Republicans to agree on a division of equal air time, but the latter refused and the Democrats came up with the idea of televised debates as a way to get their candidate as much air time as possible(Self). And Kennedy was more than happy to take on his opponent on air.

On the one hand, there was a Republican ex-congressman, ex-senator, the vice-president for eight years who had proved over and over that he was qualified for the job; on the other hand there was a Catholic family man who did have a political background, but was deemed too young for the job at first look. Nixon had an advantage over Kennedy because he knew the battlefield, and the presidential election is just that. One might recall that during the Civil War, the Confederate states were the minority, but their knowledge of the battlefield made them victorious in the first half of the battles and gave them the false hope of a quick war after which they would emerge again victorious (Brinkley 376-7); Kennedy and Nixon, both soldiers, knew a good fight when they saw one. It was at this time that the true power of television became apparent even more so than during the Checkers speech, as Kennedy’s relationship with the camera helped him in making a connection with the American people (Zelizer 20).

After both parties had agreed to participate, they set up a series of debates that would take place on television. Both parties agreed on the terms and the arguments that would be touched upon at each debate. The first is the most famous one, with over hundred-thousand viewers; there was, however, a disagreement over the panel that would host the event. This disagreement did not come from either party but from within the executives who did not think to include the press in the process. A final agreement was drafted, according to which the first and last debate would hold a panel of newscasters, while the second and third would also have members of the press among the panelists (Self).

When analyzing the debate, one must first watch closely what happened on screen. Even today “there is no extant evidence that television images had any impact on audience reactions” (Druckman), yet they clearly influenced a lot of voters enough to bring about two different groups: those who claimed that Kennedy won, and those who thought Nixon did. As for what the audience saw at home, there were two men: one “looking like robust and suntanned Charles Atlas versus a pale and puny Count Dracula in need of a shave” (Allen and Nixon 141); a sweaty Nixon often agreeing with the points raised by his opponent instead of challenging them, and finally one man avoiding eye contact while the other looking directly into the camera (CBS). While what happened in front of the camera was decisive, there should be a parenthesis drawn to discuss what happened behind the scenes. It has to be noted that after the debate there were several legends on how Kennedy was simply more appealing on camera. Although that maybe true even today, he did not have “a fever of 102 and was [not] on antibiotics”, nor was he asked if he would like to postpone the debate, to which Nixon replied: “No, people will think I’m a chicken” (Self). A decisive aspect of the debate was the illusion that Kennedy did not wear makeup(“The Kennedy-Nixon Debates”).It might not seem important at first, but looking at the importance of presidential debates in the 21st century, this small detail should not go unnoticed. It is also relevant because during the primaries Kennedy had debated future vice-president Hubert Humphrey who would become Nixon’s opponent later in 1968, and the Kennedy campaign was clever enough to make others believe that by having a standard television makeup, Humphrey was putting on a false face. This was a critique the Nixon campaign was not going to risk (Self).

The debate, as stated above, is of such importance because it demonstrated that people factor in looks and appearance when choosing their candidate, aside from current issues or party preferences. Both parties had good arguments, which underline how on radio the favorable candidate remained Nixon, even if many remember it as a win for the Democrats (Freedman 215-216). Media came alive here; the presence of TV sets in the American households had an impact on the Presidential election, and they learned that “media events confer status on the institutions with which they deal” (Katz and Dayan 199). If only the radio had been present there would have been no question over Nixon’s victory. Television portrays body language and as such the two candidates had to be aware of the fact that everyone could see every move they made. Unfortunately just one of the two did. Even today for “some analysts, body language and non-verbal communication are some of the most important factors in determining who comes out on top on Election Day” (Keller). Taking a closer look at what people saw on television (Appendix Picture 2), one will see a confident Kennedy on the left, well composed, sitting up straight and ready for questions. On the right, however, we see an uncomfortably sitting Nixon, grabbing onto the chair and his jacket buttoned just like a little boy’s. This was the key element that differentiated the two: one appeared ready to be the man America needed, whilst the other could have easily been taken for a high schooler at a debate class. To draw a comparison to how debates have evolved since there is need to examine the latest election in the United States. The first debate between then candidates Hillary Clinton and Donald Trump took place exactly 56 years later, on September 26th, than the Kennedy-Nixon debate. Looking up articles on the debate, one by the BBC detailed the clothing of the two candidates: the color of Trump’s tie and the color of Clinton’s dress for example (Banks). The New York Times had a whole article on the black dresses of the whole Trump family, which emphasizes that not only the candidate but their family is also in the spotlight (Friedman). The setting of the debate is of equal importance: opposed to the first televised debate, the set has changed immensely. Just in the last series of debates the candidates spoke in front of a wall that had the Declaration of Independence printed onto it. Following the debate Forbes magazine printed a detailed article on how body language influences voters. The article emphasized of course that viewers’ bias always plays a role in interpreting the candidates’ movements and grimaces and smiles. Nonetheless, there is a clear approach from each participant to convey their message, and while standing behind a podium, facial expression became dominant (Goman).

The Republican team could easily assume that it would be no problem if it came to using this medium again after the success they had with the Checkers speech, “Nixon would never have agreed to meet the much lesser known Kennedy on equal terms had he not had good reason to be confident of his performing skills” (Freedman 20); but some did fear that the outcome could be negative. Many advised against the debate, partly because of not knowing how they would proceed, partly because the vice-president, being in such a high position in the chain of command, could receive questions that he could not answer due to national security reasons; but not being able to answer might reflect badly on him (Self). Nixon had behind him a history of debate classes and awards which had helped him previously in defeating other opponents in the House, and he had confidence that he would easily beat Kennedy: giving him a punch at the beginning of the campaign could cause a setback the Democrats might not recover from. Unfortunately, the first encounter covered domestic issues, which were not Nixon’s strong suit. He would have preferred to talk about foreign affairs in the first debate (Self).The plan, having backfired, left the Democrats winners mostly due to the fact that Americans living in swing states vote based on issues close to them, rather than nonchalance foreign affairs.

A monologue, or narration, like the Checkers speech, had a completely different tone and approach: Nixon was alone, and it was not a competition even if the goal was ultimately the same. The goal – convincing Americans to believe in him as an adequate leader – was achieved through radio transmissions but not through his presence on the television screen. Kennedy had a natural stance and capability of talking directly to the people, almost as if he himself was in their living room himself, or at the dinner table, as part of the family. Nixon was not “gifted neither with independent wealth, nor physical charm, nor obvious personal magnetism” the way Kennedy was (Freedman 20). Aside from the program the two candidates laid out, outside factors must also be taken into consideration, such as the year of the debate. From a political point of view 1960 was on average nothing special when it came to domestic conflicts. Americans vote based on issues and although the Cold War (pointedly from 1958 to 1964) was still active, the general population did not express interest in foreign affairs (Freedman 215-216).All this changed since the Vietnam War was witnessed through photographs and video recordings just as it was unfolding, unlike previous wars overseas, and thus the American people felt the need to get involved. Nixon might have lost the election to Kennedy because of the lack of turmoil in domestic policy, but he would win in 1968 when those policies became important and his political background could help him.

Of the series of debates, the third one is also exemplary when examining the rising power of the media and technology: this debate occurred with the two candidates on different sides of the country (one in Los Angeles, the other in New York), and they were brought together “by the miracle of television”. Other than the makeup, there was also another irregularity that the Republicans pointed out and was a cause for long debates between the two teams. Kennedy allegedly prepared notes for his third debate, although they stipulated that no help of such form could be used. To his defense, Kennedy said that he wanted to quote old speeches, more precisely: “If I’m going to quote the President of the United States on a matter involving national security, he should be quoted accurately”(Self). The last quarrel among the two campaigns was around a fifth debate, which was too close to the election date and as such both parties seemed to want to back away from it, without taking the blame and appearing weak (Self). Although he was beaten, Nixon was not bitter. He and Kennedy had a friendship that had been fortified when the former was a senator and even if many believe that the conflict between them just kept growing, in fact they had great respect for each other, no matter their political stance (“John F. Kennedy”). Even if live debates were put on a halt for sixteen years after these two fought their battle, live television debates were later on exported into other countries, many that were much more reluctant on democracy, and this is a true testament to the power of active media (Katz and Dayna 204).

Unlike Nixon, Kennedy was indeed very “attentive to the press” (Zelizer 20). He made covering the campaign as easy as possible, by handing out transcripts of his speeches just minutes after they were made. By cutting back on research and fact-checking, the life of the press was made a lot easier (Zelizer 20). This was a practice that the press looked for in every candidate afterwards, and also one of the reasons Nixon disliked them very so much.

1.3 Nixon vs. Humphrey: Nixon No. 2

What followed the defeat against Democratic nominee John F. Kennedy is a period that Nixon himself referred to as the “Wilderness Years”. With the strong belief that a life as an elected official was behind him, Nixon still rallied and campaigned for Republicans while working in a legal office (“The Vice-President”). However, 1968 was a very different time in US history. The Vietnam War had more opponents than supporters and the Civil Rights Movement became stronger than ever with the death of Martin Luther King Jr., giving it that last push for victory (“United States”). The importance of dealing with national affairs was imminent.

1968 was a different year from a media point of view as well. The young and strong image that the press created of Kennedy quickly made him something that was unprecedented at the time: he became a celebrity president. Everything the president did had to be televised very quickly, starting from the landing of Air Force One to any and all the trips. Even if on his diplomatic missions Nixon had appeared plenty of times in front of the camera, he had to ensure in this second election campaign that the events of that first presidential debate did not repeat themselves. As a matter of fact he came back as a whole new person. His iconic victory sign can be dated back to the election of 1968, and the most famous photographs are of him smiling into the camera and waving diligently to the crowd. It is impossible today not to include the victory sign when Nixon is satirized. The only way Nixon was able to win the election was learning how to handle the media, use it to his advantage the way Kennedy had. Because it was not “the mass media that shaped public opinion but rather the holders of power who shaped public opinion by using the media as their agents” (Fellow 331).

Richard Nixon won every Republican primary he entered, exactly because upon reentering the political sphere he came back as a different person. For a long while it was unclear who his opponent would be in the general election (“United States”), as President Lyndon B. Johnson decided to withdraw from the race, vice-president Hubert Humphrey was unpopular because of the Vietnam War, having sided with the President, all along, and the best possible candidate for the Democrats, Robert Kennedy, followed the faith of his older brother (“United States”).Once having claimed a wish to run for the presidency, Humphrey came out as the leader of the party, but internal conflicts within the Democratic Party helped Nixon’s campaign.

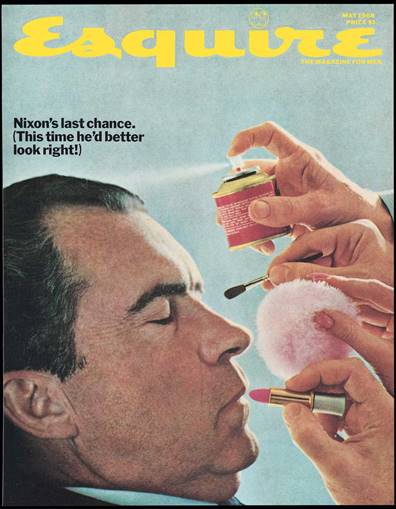

Vice-president Humphrey became the official candidate for the Democratic Party, but was overwhelmed by Nixon’s tactics. Nixon replaced the debates of 1960 with town meetings, where people could talk to him, ask him their questions, and he would answer. Although the people might have believed that their questions covered every topic, they were not experienced in questioning, while Nixon was very skilled with his answers (Freedman 44). Esquire magazine even did a cover on him (Picture 3), on which he is sitting in the make-up chair and the title page said: “Nixon’s last chance. This time he’d better look right!”, which was a reminder of the Kennedy debate. The picture was not only satirical of the election that Nixon had lost, but it also emphasized the importance of looks. Presidents had been on the cover of magazines before, but their appearance, their features, and the presidential image was never brought into question. This cover emphasizes how the smallest of details were of crucial importance. On the outside Nixon had already lost once and the idea of a loser was quite negative. Innovations in his campaign strategy and his presence on camera had to be improved. Exploiting that, a whole new kind of firm emerged by the late sixties which dealt with political media consulting. Candidates started using these firms and slowly the hiring and firing of these consultants started to become news as well. With the publication of Joe McGinniss’ The Selling of the President in 1968, “which documented the packaging of presidential candidate Richard M. Nixon” (Fellow 326-7), need for consultants and their services saw an increase.

Picture 3: “Esquire’s May 1968 cover had some fun with a stock Nixon photo mixed with some cosmetics ad copy”. (Digital image. Hollywood & Politics. Accessed 9 Dec. 2016.)

For this election, Nixon had a whole new way of looking at campaigning and his tactics and ideas have since become part of every single presidential campaign, even if at the time they were considered unethical. Perhaps making the masses believe they are in control of the conversation is not welcome even today, but there is an example of a major change that is very much used even today. Such innovation was for the president to be constantly campaigning as it was never too early to start preparing for the next election season (Freedman 45).

When it came to the 1968 election, Nixon had an advantage as well as luck on his side. First of all, the voters were composed of a lot of young men opposing the Vietnam War, which Nixon proclaimed would end if he were elected, as his campaign slogan was “Peace with honor” (Fellow 338). At the same time there was a silent majority in the American households that sought the tranquility and peace that had reigned during the Eisenhower and Kennedy presidency. American history proved that it is usually the candidate with a plan that gets elected. Moreover, Nixon could have lost some of the southern states to Humphrey, however, these voted for a third candidate, George Wallace, running for his own American Independent Party. Wallace secured almost 10 million votes, which did not go to either major candidate (Pearson). Although it was not unprecedented that a third party would arrive so close to the White House, it is of historical importance for its rarity. Richard Nixon won the election. It was close, but the American people seemed to demand a leader who could guide them out of the mess they were in.

2. President Richard M. Nixon

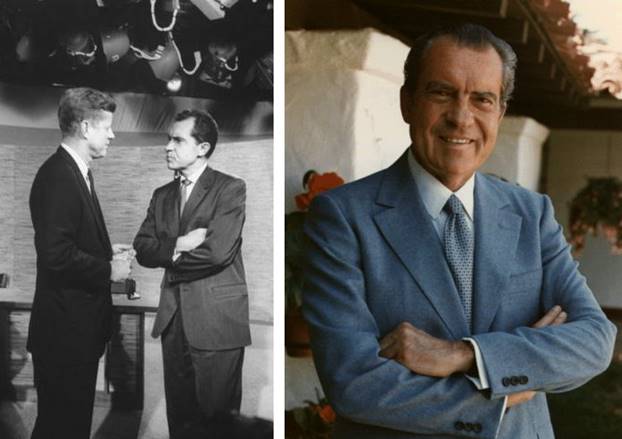

The problem at hand, after the election, was that media events produce the expectation of openness in politics (Katz and Dayna 204), and even if Richard Nixon was politically more favorable than his opponent Humphrey, this openness was never fully mastered. He also had to look convincing in the part of the likable celebrity president that Kennedy invented. It was understood that there had to be changes made, as Nixon himself confessed after losing to Kennedy that “I believe that I spent too much time in the last campaign on substance and too little on appearance” (Eggert). In the end what he said and what his body portrayed were two different men and for him to be successful there was a need for the two to come together. The following chapter will detail the appearance of the second Nixon, in contrast with the old one through photographs that clearly showcase a difference in personality and campaigning tactics.

Picture 4-5: Left,Second presidential debate between Kennedy and Nixon, a behind the scenes photograph (Digital image. Psychology Today. Gettyimages, 06 Oct. 2014. Accessed 09 Jan. 2017.). Right, “President Nixon shown relaxing at the ‘western White House,’ his estate in San Clemente, California” July 9, 1972. (Digital image. Social Security History. N.p., n.d. Accessed 09 Jan. 2017.)

Most research concerning his body language focuses on the Kennedy debate, which is useful for drawing comparison as to how he changed during the “Wilderness Years”. Before the debate Nixon stood with his arms crossed next to Kennedy (Picture 4-5, left), he looked smaller, weaker even compared to his opponent. Having one’s arms crossed can be read as a sign of protection and as such intimidation can be deducted from one’s body language. Opposite to a picture of Nixon smiling as president (Appendix Picture, 4-5 right), it would seem silly to draw the conclusion that his arms being crossed are anything but a sign of strength. In the second image, finally, the mind and body were in sync (Keller), and having your arms crossed is often done simply to enhance one’s muscles, again, for protection, or simply to display power. But people are often left with this image of Nixon being closed off and one of the reasons for that might be popular culture and contemporary media. Countless TV shows and several movies focused on Nixon, either his time as President or on the scandal, and in them Nixon is portrayed similarly. Famous examples include Oliver Stone’s Nixon (1995), where the president was played by Anthony Hopkins, and other lesser known movies like Elvis & Nixon (2016), where he was portrayed by Kevin Spacey (Appendix Picture 6-7), once again with his arms crossed. Nixon was prone to his stance and even if many times it can be read as a clear indication of fear, it can very well be the exact opposite.

Picture 6-7: Left, Nixon. Dir. Oliver Stone. Perf. Anthony Hopkins. Illusion Entertainment, 1995. DVD. Right, Elvis & Nixon. Dir. Liza Johnson. Perf. Kevin Spacey. Amazon Studios, 2016. DVD.

Photographs of Nixon winning the election show him as he opens his arms in the air with the victory sign on both hands. This was the image he had created and it was the one that he began his career in the White House with (Appendix Picture 8), and the one that he decided to end it with (Picture 11). Having your arms up in the air makes you an open target; however, this image enforces immortality and security. Nixon managed, by simply raising his hands, to come across as more stable and secure than ever before. The little school boy image that people had of him next to John Kennedy was shattered into pieces as this secure candidate emerged.

Picture 8: “Nixon’s The One” was the slogan of his campaign. The candidate was riding across Chestnut Street in Philadelphia in September, 1968. (Photo by Halstead, Dirck. Digital image. Gettyimages. Hulton Archive, 01 Jan. 2000. Accessed 09 Jan. 2017.)

Once within the White House again, Richard Nixon had to imitate the part of the celebrity President even more than he did during the campaigns. It was then crucial to be in the public eye as “for the process of image-building, leaders rely on the media to carry their messages to the public” (Just), thus it was no longer just his politics that had to be up to the standards but himself as well. In the end one might conclude that he had had it easier as vice-president as most of the limelight was not on him but on Eisenhower. The Kennedy-like presidency never actually came about, as the natural relationship Kennedy had had with the press was something the Nixon administration never quite grasped. Furthermore, he kept his family affairs private. The Kennedys often let photographers take pictures of them during vacations or family encounters, whilst the Nixons only did so when they were forced into formal situations. Although there are several photos of Nixon and his wife walking their dog at Camp David, or just spending time together, he never showed a side of him that people could relate to. The closest it got was the wedding of his eldest daughter, which was held at the White House and to which the press was invited. During his time in office, only one kind of photograph emerged of the President and that was usually of him sitting at his desk at the Oval Office, either on the phone or talking to his team (Picture 9). Even in the pictures where he is relaxing there was always a pile of papers in his hands. The image Nixon wanted to sell of himself was of a man always at work for the nation that elected him, and the work never ended.

Even if Nixon was not active in his relations with the media during the first half of his presidency, the media itself was very active. When it came to Nixon they became quite passive since with negotiations of foreign affairs they had enough material to print already. Not to mention when the Vietnam War alone was a massive media event: “Television brought the brutality of war into the comfort of the living room. Vietnam was lost in the living rooms of America – not on the battlefields of Vietnam” (“Marshall McLuhan Interview 1967”). At first, media, or simply put television, had the power to unite the family, to gather them together and spend time sharing what they saw (Katz and Dayna 206). Television was the friend of the family, but this deteriorated over the years, first with the assassination of John F. Kennedy and then “also made Americans uneasy as it captured violent and shocking pictures of race riots and combat engagements of the Vietnam War” (Fellow 305). Media events provided the people with enough material to rally against the war: media became a very powerful weapon. Although the press was simply reporting the news, they ended up aiding those who sought change in the government’s approach to the war and other policies (Katz and Dayna 200). The public’s active participation has always been fueled by the press, both knowingly and unknowingly, and the Vietnam War was just another example.

Picture 9: Richard Nixon meets in the Oval Office with top aides, left to right, H.R. Haldeman, Dwight Chapin and John Ehrlichman.(Digital image. Gettyimages. Time & Life Pictures, n.d. Accessed 09 Jan. 2017.)

As far as the press’ urge to be present in the President’s life was concerned, it was satisfied by covering the unraveling of the Vietnam War, the diplomatic recognition of communist China and the détente period with the Soviet Union (Szabó 88).

Nixon was, however, still under pressure when it came to domestic affairs. As it was noted earlier in this paper, once the Vietnam War became part of the American household, protests and riots followed (Isserman and Bowman 141). “Nixon–a candidate for reelection–was under fire at home from those demanding social change, racial equality, and an end to the Vietnam War” (“Détente”), and the only way he could focus on such issues was assuring that there would be no nasty surprises at America’s doorstep. At the time Nixon’s approval ratings skyrocketed, “[h]e was on his way to winning a 49-state landslide over George McGovern” (Kurtzman), but he wanted to win again, and win big, which ultimately cost him his political career.

2.1 The Downfall: Watergate

Richard Nixon got re-elected easily. He was always ahead in the polls, and with his place secure as incumbent it seemed that he would easily finish a second term in office. However, that became impossible when he decided to resign in order to avoid impeachment. That was not the beginning of the downfall of Richard Nixon, nor was it the end.

Before analyzing the causes of the first presidential resignation in U.S. history, the events leading up to it have to be explained shortly. What is today referred to as the Watergate Affair, Scandal, Conspiracy or Incident was a break-in into the headquarters of the Democratic National Committee housed at the Watergate office-apartment-hotel complex on June 17, 1972 (Bernstein and Woodward 13). The intent was to set up wires in order to be able to listen in on conversations, possibly gain intelligence on the candidate running against Nixon, or on any similar confidential information.

In the end it seems that Richard Nixon’s hatred of the press was not unfounded. All of it started when the press attacked him for his stance on the Vietnam War, as his promises made during the campaign were the opposite of his policies afterwards. The beginning of can be traced back to a leak from the White House to the press of the plans to bomb Cambodia (Isserman and Bowman 135). Strangely enough, when The New York Times published it, it did not raise enough attention to cause a problem, but it did send the Nixon administration on a witch hunt to determine who was to be held responsible. Again media became an active participant and it shaped relations within the White House. It can be argued that this was the beginning of the downfall that escalated into Watergate, and thus the reason for Nixon’s resignation. It can be argued that it was a minor issue, but at the time there was already mention of the recordings of conversations within the White House and a witch hunt of the sort could easily damage relations within the Nixon administration (135).Watergate was the second national crisis, after Vietnam, in which the president’s opponent was not another party or Congress but the press. There was in fact “a crisis in credibility, with part of the public doubting the press and the other part doubting the presidency” (Fellow 331-3). Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein were two reporters for The Washington Post who were assigned to deal with the Watergate break-in. Woodward was sent to the court house to listen to the hearing of the five men arrested for the break in. Even if at first it seemed like a simple case, upon entering the court room Woodward noticed an attorney ready to be assigned to the case, before any of the accused had a chance to call for an attorney (16-17). The White House, following the break in, released a statement in which they claimed that they had no involvement in the break-in, and had no ties to the men who were deemed responsible (20). The statement also included that the White House believes “the integrity of political process” (21) was harmed by such actions.

After the disclaimer, it seemed unnecessary for the two reporters to keep assuming the White House had any knowledge or involvement in the case. The question the arises as to why these reporters kept going deeper down the rabbit hole, and the reason for that was that the more information they gathered the more vital it became to find out “who authorized it” (344). Not just the break-in, but the tapping of phones, the fake letters from possible presidential candidates, the money, the pay-offs, everything was pointing to someone who was almost unreachable, and only one person fitted that description. Aside from evidence pointing to the White House, there was also the witch hunt that Nixon started when looking for the leak after the Cambodia bombings. Two of the five men accused of the Watergate break, (Howard Hunt, a former CIA agent, and G. Gordon Liddy, a former FBI agent),had already been charged with a break-in that was connected back to the White House (Isserman and Bowman 148). Due to the same players taking part in both break-ins, the press continued to investigate the matter further.

The case against the President caused uproar. Nixon himself went on a rampage to make sure the Post paid for its position and the allegations they had printed over the months about him and all of his men (Bernstein and Woodward 297). Woodward and Bernstein were running out of leads and it seemed that the President might stop them without having to lift a finger. Upon reviewing their notes, however, Woodward found one person on his list who had evaded questioning until that moment, a man named Alexander P. Butterfield, a White House aide. After finally reaching this man, Butterfield confessed, first privately and then to the Senate committee as well as the whole country that the President had a tape system installed in the Oval Office which recorded all of his conversations: “Nixon bugged himself” (362-3). As a response, the Supreme Court acted quickly and wanted the tapes to be able to either convict the President of wrong doing or clear his name. Supposedly, many requested ones did not even exist (364), and the President was reluctant to hand over the ones that did. At first his staff produced transcripts, but they were not accepted as a substitute and many indeed had been falsified as it later turned out. Out of all the subpoenaed tapes, one contained a famous 18½ minute gap of which the contents are still a mystery today (365), but speculation usually points to it being about the knowledge of the Watergate break-in between the President and his Chief of Staff H. R. Haldeman. The tapes constituted the missing piece of the puzzle.

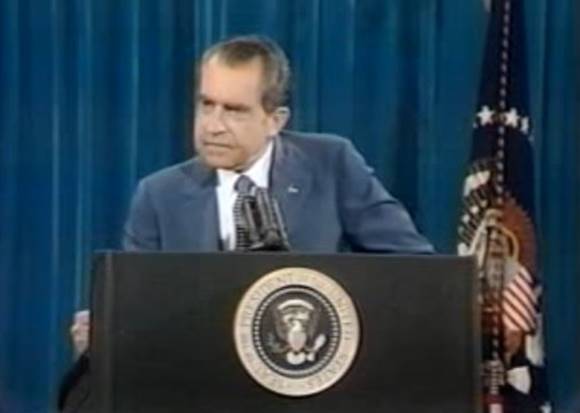

Picture 10: Screenshot of Nixon’s famous speech where he utters “I’m not a crook”. 1973. (Youtube. 25 Nov. 2016.)

On November 17, 1973 Nixon took the podium to appear in front of an audience of editors and national TV at Disneyworld in Florida (365), and just like in the Checkers speech, he spoke of the money he had earned and how he had nothing to gain from the Watergate scandal. He spoke about figures and earnings only to end in the positive note that reinforced how he was only serving the American people: “[They] have got to know whether or not their President is a crook,” and he then uttered the most famous line of his whole political career “Well, I am not a crook” (Kilpatrick; Picture 10). He seemed tense, but he maintained his innocence and promised more evidence that would prove it. Since Bernstein and Woodward were able to find out that the Committee to Re-elect the President was connected to the break-in, Nixon had no choice but admit some form of guilt. The CRP, or CREEP, was staffed by and answered only to the White House (Bernstein and Woodward 88), and the President claimed that he did make a mistake by not monitoring more closely the campaign activities. “While the President was nervous, he was not floored by any of the questions but answered them much as he does in any press conference”, which is a great argument to show how effectively he learned to deal with the press over his years as an elected official, and that he was aware of being under interrogation, even if not by the police, but by the people through the press. Most of the conference was spent talking about Watergate, not other current issues, and the President assured people that the tapes would exonerate him of any wrongdoing (Kilpatrick). Once all the tapes were out of the White House there was nothing left to do, but impeach the President because he was otherwise protected from any kind of other law-suit.

On August 9, 1974, the President sat down in front of the camera in the Oval Office to deliver the only resignation speech in the history of American Presidents to date. In his speech he praised his vice-president, reassuring the American people that they will be served well and he said that resigning “before my term is completely abhorrent to every instinct in my body” (“Resignation speech”), which amidst all the lies and cover-ups was the most honest sentence ever uttered by him. It had that human component that many had missed from him; it made him earthly, sentient and remorseful. He went on to talk about all the good things that America achieved during his time in office, in other words, all those politically significant acts and treaties.

Picture 11: Nixon Leaves the White House after His Resignation over the Watergate Scandal in 1974. 1974. (Richard Nixon’s Life and Career. CNN. Accessed 25 Nov. 2016.)

Media events have the capability to reedit collective memory and as such the president’s resignation, with all the charges unclear at the time, was able to echo sad partings, such as John F. Kennedy’s (Katz and Dayna 212). But the resignation speech was not considered complete by many. What the American people lacked was the admission of guilt or the recognition that his actions were improper. Nixon was then facing law suits and criminal investigations, as he was no longer the chief-executive. However, he escaped prosecution as he received a full pardon by then President Gerald Ford for any and all crimes against the United States. The media’s involvement caused changes of immense magnitude: “the Watergate hearings gave new prominence to the legislative branch of government” (Katz and Dayan 199), and as such, he would have been free to be questioned as the president-status did not defend him anymore. People had to wait a long time to find out what really happened inside the White House in the year of the Scandal. Then President Gerald Ford commented “our long national nightmare is over” (Isserman and Bowman 147), while supposedly talking about the Vietnam War but for many that also referred to Watergate. Media, overall, affects the international image of the society that they are taking place in (Katz and Dayan 201). This explains why during the Cold War the most prominent information about Nixon outside the country became the Watergate Scandal, as it was covered a lot more than most of the president’s acts during his time in office.

2.2 Frost vs. Nixon

While waiting for the scandal to blow over, Nixon retreated to his home in California and did not agree to any public appearances for three years to come. His image was shattered and he could not run for office again. California was very far from Washington for a politician who had been active for almost 30 consecutive years. This subchapter had to be included in the paper because it details how his taped confession of wrongdoing within the White House essentially brought about his political suicide. Having been pardoned, Nixon could have easily, with enough time passing, get back into politics and rally for the Republican Party the same way he had done years before. Today, when looking up political candidates, it is hard not to find some sort of scandal: cheating, embezzling, inappropriate behavior via photos or tweets or simply racist comments (Zernike). Candidates seeking higher office live in an age when everyone has a smart phone in their pockets and everything can and everything will be recorded eventually. The president was caught because of recordings as such; journalism was praised for seeking the truth at the time. Today, on the other hand, with so many scandals out there, even journalism is discredited sometimes, and their credibility has somewhat decreased as those involved in the scandals have waged war against “the media” (Fellow 332). Think of candidates like Anthony Weiner, who was caught twice “sexting” someone other than his wife, yet he is still an active politician, who might not run for higher office but is nonetheless present in Washington (Zernike). The same can be said about Donald Trump, who had in his life time over 4,000 lawsuits, many of which were not even concluded by the court when he was elected into office in 2016 (Penzenstadler). It is interesting to see how so many politicians are barely forced to see the consequences of their actions, while Nixon is said to have committed political suicide when he admitted his involvement in the Watergate Scandal.

It was three years after his resignation, back in 1974,that Nixon agreed to an interview. Because of it, he made history one last time, but this time it was not because of a speech he prepared to get in the good graces of the American people, and he did not make history alone. David Frost, a British television host, known for interviews conducted with The Beatles, Maria Callas and Muhammed Ali, pushed for an interview with the President, which he paid for with money out of his own pocket (“David Frost, the interviewer”). Most television networks were not interested in an interview conducted by a Brit, as they would have preferred an American, but Frost did not give up. He set up a team with journalists Bob Zelnick and James Reston, Jr. and they went over every single tape recorded in the White House in the hopes to find something more, which they did.

The interview itself lasted several hours, stretching over a couple of days, with the Watergate chapter becoming the most famous one, and with it, David Frost became a very famous journalist since he managed to get a confession out of Nixon. As indicated earlier, people wanted an apology, as they do even today from all politicians, from actual presidents such as George W. Bush admitting that there were no weapons of mass destruction in Iraq, to presidential candidates like Hillary Clinton apologizing several times over her leaked emails. The reason that they did not get one until this interview from 1977 can be summed up in Nixon’s own words, which he uttered with regards to America’s military during the war,: “When the President does it that means that it is not illegal” (“War at home and abroad”).

On television if an event is broadcast live there is pressure over whether or not it will succeed (Katz and Dayan 191). Because of this the interviews were not broadcast in the order of shooting. The first episode that aired from the interview series was the one discussing Watergate, and it had the most views as well (“David Frost, the interviewer”). In the historical-fiction movie entitled Frost/Nixon, the President’s motivation for confessing was the realization that this interview was not a comeback to political life, but a chance to set the record straight (Frost/Nixon). If one watches the whole interview they will see that in most cases Nixon had the upper hand and his knowledge of years of dealing with the press came in handy, but Nixon reacted aggressively and cracked under pressure due to his temperament (Appendix Picture11).

First, Nixon stopped Frost while the latter read out a quote by the President: “Yeah, all right, fine, let me just stop you right there, right there. You’re doing something here, which I’m not doing and I will not do throughout this broadcast” (“The Watergate Interview”) he said that as he felt that Frost was quoting him out of context. Nixon told him that he himself did not prepare notes and had agreed to the interviews on Frost’s terms, but he would not be misquoted. Frost went on to ask him about his motives and Nixon approached his answer as a lawyer for the defense, and he referred to Frost as “the prosecutor”. Nixon claimed that his defense is that he did not have a “corrupt motive” and the obstruction of justice could only be justified if the guilty party had corrupt motive. Nixon said: “My motive was pure political containment, and political containment is not a corrupt motive” (“The Watergate Interview”). After questions about whether burning the tapes was an option, or why illegal payments were not terminated, Nixon stopped Frost again and delivered what many found to be a satisfying confession. Nixon said: “One is: there was probably more than mistakes; there was wrongdoing, whether it was a crime or not; yes it may have been a crime too. Second: I did – and I’m saying this without questioning the motives – I did abuse the power I had as president, or not fulfil the totality of the oath of office. And third: I put the American people through two years of needless agony and I apologize for that” (“The Watergate Interview”) (Picture 12).

Picture 12: Screenshot of the famous David Frost interview. 1977. (Youtube. 25 Nov. 2016.)

This one-on-one interview was the last time people got to see the real Richard Nixon, and even if his regret was embedded among the lines of his confession, he was forever buried under the notion of willingly committing unlawful actions against the people who elected him into the White House.1970 “marked an irresistible rise of news-media power” (Fellow 331). The mass media, especially in this case television, was able to hold a mirror to society and became a significant force that contributed to the shaping of the nation’s cultural and political fabric (Fellow 331). Because of that, the Frost/Nixon interview will always be one of the most well-known milestones in journalistic history, as well as media history, and on a political level it was not only unprecedented, but also unique in its format.

Conclusion

Digging through digital archives the name and figure of the 37th President of the United States is bound to be encountered several times. Even if on a larger scale Nixon is rarely debated anymore when media history is concerned, on a smaller scale it does show that he was an incredibly important figure.

While running for vice-president he became the first to hold a televised speech with political intent. The intent was to remain on the presidential ticket and he was successful. The speech was viewed by over 60 million people and this helped media experts get a grasp of the success that lay in the relationship between television and politics. Slowly the Vice-President became active as an “ambassador” for the U.S. His trips and meetings were reported quite frequently and media shaped him into a hero as they understood that people like to read and see fairytales. Nixon’s image was exaggerated and this led him to the false hope of being able to win the presidential seat. As it is dubbed the Kennedy-Nixon debates, and not Nixon-Kennedy debates, the loser party falls into the shadows over the years. Nonetheless, he was very much present at the first televised presidential debate, and the outcome of it would have been very different if Kennedy were not the opponent. Once in office, JFK created a “movie-star politician”, an image that the candidates who followed him were forced to live up to by the media.

When Nixon returned to the political scene, he was adamant on not making the same mistakes again. He studied the media and the press, thus he was more secure in his position and his knowledge helped him get elected. It was unforeseen at the time, however, that the Vietnam War would go on despite his promise to end it quickly and efficiently, and for this the press attacked him. He had already resented the press for expecting him to be a celebrity instead of a politician, and now with constant attacks, this resentment only grew stronger. Once the war ended Nixon got re-elected easily but there was still a fight with the press awaiting him that he would lose. Due to the freedom of the press, and because there were men who believed that even the president should be held responsible when acting unlawfully, two reporters from The Washington Post set out to discover what lay behind the Watergate break-in. Nixon was brought down by his own hands, as digital testimony in the form of recordings inside the White House became indisputable evidence of his knowledge and involvement in the break-in. In order to avoid impeachment, Nixon became the first president, and so far the last, to ever resign from the White House. However, his resignation was not the end of his battle with the media. The biggest milestone in media history followed three years after his resignation, in an interview conducted by David Frost. In this interview, which was recorded, televised, reprinted, reshot and even made into a theater play, the ex-president was held responsible and in front of the cameras, he admitted to his involvement. The media promised and the media delivered a confession by a man who was untouchable after the presidential pardon. This would signal the end of his political career, and the interview itself would live on for its unique and unprecedented format.

Sometimes it seems that recordings only have one interpretation, because words are there in black and white: they have a precedent, a setting, an exact time frame and the consequences are clear as well. Yet it seems that with this president in particular, there are a lot more angles that can be covered when reopening the digital archives. This paper wished to demonstrate how the active entity of the media had a hand in shaping history. The countless books on media history might mention the Kennedy-Nixon debate when talking about television, and they might even bring up how the Vietnam War was lost within America way before it was lost in the battlefield. However, they do not detail some of the biggest game-changing events, and for that reason the impact of the media was chosen to be observed in this paper through the political career of a president within the political history of the United States.

Works Cited

Printed and Electronic Sources

- “Amendment XX Presidential Term and Succession, Assembly of Congress.” National Constitution Center. N.p., n.d. www.constitutioncenter.org/interactive-constitution/amendments/amendment-xx. Accessed 11 Nov. 2016.

- Allen, Gary, and Richard Nixon. The Man Behind the Mask. Western Islands, Boston–Los Angeles (1971). Ebook.

- Banks, Libby. “What Clinton and Trump’s Clothes Tell Us about Them.” BBC News. BBC, 26 Sept. 2016. www.bbc.com/culture/story/20160926-trump-and-clinton-go-head-to-head-in-a-battle-of-the-image. Accessed 5 Jan. 2017.

- Barnes, John A. John F. Kennedy on Leadership: The Lessons and Legacy of a President. New York: AMACOM Div American Mgmt Assn, 2005. Print.

- Bernstein, Carl, and Bob Woodward. All The President’s Men. New York: Warner Paperback Library, 1975. Print.

- Black, Conrad. Richard M. Nixon: A Life in Full. New York: Public Affairs, 2008. Ebook.

- Brinkley, Alan. The Unfinished Nation: A Concise History of the American People, Volume I. Vol. 11. McGraw-Hill, 2015. Print.

- Buurman, Gerhard M., ed. Total Interaction: Theory and Practice of a New Paradigm for the Design Disciplines. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter, 2005.

- “Détente”. History.com. A+E Networks. 2009. www.history.com/topics/cold-war/detente. Accessed 25 Nov. 2016.

- Druckman, James N. “The Power of Television Images: The First Kennedy-Nixon Debate Revisited.” The Journal of Politics 65.2 (2003): 559-71. www.jstor.org/stable/10.1111/1468-2508.t01-1-00015. Accessed 10 Nov. 2016.

- Eggert, Max. Brilliant Body Language: How to Understand and Interpret Our Secret Signals. Prentice Hall Life (Online publishing surface), 2010. PDF.

- Ernst, Wolfgang. Stirrings in the Archives: Order from Disorder. Trans. Adam Siegel. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield, 2015. Print.

- Fellow, Anthony. American Media History. Belmont: Thomson Learning, Wadsworth. 2005. PDF.

- Freedman, Carl. The Age of Nixon: A Study in Cultural Power. London: John Hunt Publishing, 2012. Ebook.

- Friedman, Vanessa. “In the Final Presidential Debate, the Trumps Go Dark.” The New York Times. The New York Times, 20 Oct. 2016. www.nytimes.com/2016/10/21/fashion/debate-melania-trump-hillary-clinton.html?_r=0. Accessed 5 Jan. 2017.

- Goman, Carol Kinsey. “Body Language In The Presidential Debate Reveals More About Us Than About The Candidates.” Forbes. Forbes Magazine, 27 Sept. 2016. www.forbes.com/sites/carolkinseygoman/2016/09/27/body-language-in-the-presidential-debate-said-more-about-us-than-about-the-candidates/#3c592f5f5332. Accessed 5 Jan. 2017.

- Isserman, Maurice, and John Stewart Bowman. Vietnam War. Infobase Publishing, 2009. PDF.

- Katz, Elihu, and Daniel Dayan. Media events: The live broadcasting of history. Cambridge: Harvard UP. 1992. PDF.

- Keller, Jared. “Can Body Language Predict Elections?”. The Atlantic. 29 Oct. 2010. www.theatlantic.com/politics/archive/2010/10/can-body-language-predict-elections/65424/. Accessed 16 Dec. 2016.

- Kilpatrick, Carroll. “Nixon Tells Editors, ‘I’m Not a Crook’”. The Washington Post. 18 Nov. 1973. www.washingtonpost.com/wp-srv/national/longterm/watergate/articles/111873-1.htm. Accessed 13 Oct. 2016.

- Kuntzman, Gersh. “Donald Trump is aiming to be the most anti-media President since Richard Nixon”. New York Daily News. 22 Nov. 2016. www.nydailynews.com/news/politics/donald-trump-aiming-anti-media-president-nixon-article-1.2882837. Accessed 25 Nov. 2016

- Nixon, Richard Milhous. “Resignation speech.” 9 Aug. 1974. The White House, Washington D.C. Keynote Address.

- “Nixon and Khrushchev have a ‘kitchen debate’”. History.com. A+E Networks. 2009. www.history.com/this-day-in-history/nixon-and-khrushchev-have-a-kitchen-debate. Accessed 9 Sept. 2016.

- Ornstein, Norman J. “Washington: 2, Watergate Backlash.” Change 11.4 (1979): 52-53. www.jstor.org/stable/40163906. Accessed 11 Nov. 2016.

- Pearson, Richard. “Former Ala. Gov. George C. Wallace Dies”. The Washington Post. 14 Sept. 1998. www.washingtonpost.com/wp-srv/politics/daily/sept98/wallace.htm. Accessed 11 Sept. 2016.

- Penzenstadler, Nick, David Wilson, Steve Reilly, John Kelly, Karen Yi, Pim Linders, and Jeff Dionise. “Dive into Donald Trump’s Thousands of Lawsuits.” USA Today. Gannett Satellite Information Network, n.d. Accessed 6 Jan. 2017.

- “Richard M. Nixon, 36th Vice-president (1953-1961)”. United States Senate. N.p. and n.d. www.senate.gov/artandhistory/history/common/generic/VP_Richard_Nixon.htm. Accessed 1 Sept. 2016.

- Riechmann, Deb. “Nixon Urged Hiss Indictment.” The Washington Post. 13 Oct. 1999. http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-srv/politics/feed/a52881-1999oct13.htm. Accessed 10 June, 2017.

- Rosen, James. “David Frost, the interviewer who cracked Nixon’s shell, leaves a historic legacy”. The Washington Times. 1 Sept. 2013. www.washingtontimes.com/news/2013/sep/1/david-frost-the-interviewer-who-cracked-nixons-she/. Accessed 11 Oct. 2016

- Schwartz, Richard D. “President’s Message: After Watergate.” Law & Society Review 8.1 (1973): 3-5. www.jstor.org/stable/3052803. Accessed 10 Nov. 2016.

- Self, John W. “The First Debate over the Debates: How Kennedy and Nixon Negotiated the 1960 Presidential Debates.” Presidential Studies Quarterly 35.2 (2005): 361-75. www.jstor.org/stable/27552687. Accessed 10 Nov. 2016.

- Szabó, Éva Eszter. “Fence Walls: From the Iron Curtain to the US and Hungarian Border Barriers and the Emergence of Global Walls.” Review of International American Studies 11.1 (2018)

- “The Kennedy-Nixon Debates”. History.com. A+E Networks. 2010. www.history.com/topics/us-presidents/kennedy-nixon-debates. Accessed 18 Jan. 2015.

- “The Vice-president”. The Nixon Library and Museum. N.p. and n.d. www.nixonlibrary.gov/thelife/apolitician/thevicepresident.php. Accessed 31 Aug. 2016

- “Trump Owes Us His Tax Returns Now More than Ever.” The Washington Post. WP Company, 15 Nov. 2016. www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/president-elect-trump-owes-us-his-tax-returns-now-more-than-ever/2016/11/15/d69ffe8a-aab8-11e6-8b45-f8e493f06fcd_story.html?utm_term=.b3304b76ab2b. Accessed 6 Jan. 2017.

- “United States presidential election of 1968”. Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica OnlineEncyclopædia Britannica Inc., 2016. www.britannica.com/event/United-States-presidential-election-of-1968.Accessed 11 Sept. 2016.

- Zelizer, Barbie. Covering the body: The Kennedy Assassination, the Media, and the Shaping of Collective Memory. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 1992. Print.

- Zernike, Kate. “Technology and the Political Sex Scandal.” The New York Times. The New York Times, 11 June 2011. www.nytimes.com/2011/06/12/weekinreview/12pols.html. Accessed 6 Jan. 2017.

Movies, Documentaries and Transcripts

- All the President’s Men. Dir. Alan J. Pakula. 1976. DVD.

- CBS. “TNC:172 Kennedy-Nixon First Presidential Debate, 1960.” Youtube, uploaded by JFK Library, 21 Sept. 2016. <www.youtu.be/gbrcRKqLSRw>.

- Elvis & Nixon. Dir. Liza Johnson. Perf. Kevin Spacey and Michael Shannon. Amazon Studios, 2016. DVD.

- Frost/Nixon. Dir. Ron Howard. Prod. Ron Howard, Brian Grazer, Tim Bevan, and Eric Fellner. By Peter Morgan. Perf. Frank Langella and Michael Sheen. Universal Pictures, 2008. DVD.

- “John F. Kennedy.” 10 Things You Don’t Know About. Writ. Johnathan Walton. Dir. Mark Cole. History Channel, 2012. TV Show.

- “Marshall McLuhan Interview 1967.” YouTube. YouTube, 12 July 2009. www.youtube.com/watch?v=OMEC_HqWlBY. Accessed 06 Jan. 2017

- Nixon. Dir. Oliver Stone. Perf. Anthony Hopkins. Illusion Entertainment, 1995. DVD.

- Nixon, Richard Milhous. “Checkers Speech”. Evergreen Valley College, Media Services, 1975. Recording.

- “The Watergate Interview.” Interview by David Frost. Frost/Nixon. CBS. California, 5 May 1977. Television. Transcript.

- “War at home and abroad.” Interview by David Frost. Frost/Nixon. CBS. California, 19 May 1977. Television. Transcript.

Copyright (c) 2018 Eszter Zsuzsanna Csorba

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.